Da Kou, Dancehalls, Discovery

Yan Jun’s 16-page tome — a meta-narrative cobbled together from reviews of anything he could find in Lanzhou, including local releases, obscure Swedish metal bootlegs, and Mazzy Star cover CDs — was well received at Music Life. Actually, it was partially received. “Page 7 or 8 was lost,” recounts Yan, “so the editor split it into two articles and published them both.” He soon got more offers. He found a random gig contributing to a State-subsidized industrial technology newspaper with an anomalous two-page music spread in each issue. The paper’s editors had no point of reference for the subject matter, leaving Yan and his colleagues complete freedom. “We used nicknames, pen names. If you collected all the pen names you could find a poem. We just picked anything we liked, wrote about any music, nobody knew… There were several times we wrote about music that didn’t actually exist.”

Yan’s anarchic sensibility naturally led him to contribute to Punk Generation (朋克时代), a short-lived publication founded by a Guangzhou businessman and edited by early rock writer Yang Bo. In the effectively pre-internet environment of late-1990s China, Punk Generation provided a powerful national platform for disaffected youth to voice their grievances with mainstream society, to profess their membership in a shared subculture, and to place this subculture in historical context with punk, electronic, and industrial music movements from across the world.

Punk Generation Vol. 2 cover and inside spread featuring No’s Zuoxiao Zuzhou

Although people like Yan were constantly pushing the boundaries of what could be considered acceptable as music, and although his tastes rapidly outpaced local bands, the subculture he belonged to was populated by a single mythic figure: the rocker. “In the mid-90s, the first generation of experimental musicians, no exception, everyone was [a] rocker,” Yan Jun says. “Anyone who was not in the underground rock scene… getting drunk… probably belonged to the boring, materialistic part of society… All the earliest experimental, noise, electronica, and free-improvisation musicians originated from this scene. It was a dejected, rebellious scene searching for a radical, and very loud, mode of expression.”

In mid-1990s Lanzhou, Yan Jun and his friends appropriated apathy, ennui, and rock ‘n’ roll as tools of radical rejection. The first widely distributed Western music in China was country music in the John Denver mold. “In the 90s, there was also Enya. Ohhh, everybody listened to Enya. And Yanni. [Starting] from this country music, you can draw a line to New Age.” From there, Yan Jun built up his musical vocabulary by picking up the most extreme releases he could find, progressing from his first two purchases, a Queen Greatest Hits cassette and New Jersey by Bon Jovi, to random discs from Godflesh and John Zorn. These were not official imports but rather da kou, surplus stock from Western labels smuggled into China and sold illicitly, marred by a vertical gash intended to prevent resale.

For Yan and his friends, da kou became the bedrock of social life. A new cassette purchase was enough to prompt a party, a long night of drinking, even a cross-country trip. “Each city had a small underground club, maybe two or three or four different groups of people… I knew one guy, a fan of Slayer. He lived in another city… Just to listen to one Slayer cassette, he traveled [950 miles] from his city to Lanzhou. When we met, we drank and we listened to music and we guessed, ‘Who’s this band? You win, I drink.’ This music was very important in this small community.”

Aside from sitting around each other’s apartments listening to the latest da kou haul, the options were limited. Various local dancehalls had a “disco hour” from 9 to 10 PM that would feature music heavier than the normal rotation of saccharine Mandarin pop. Yan’s circle frequented Seahorse Club, a bar carpeted with cigarette butts, bottle caps, and other accumulated filth. Yan’s band friends worked there and would play thrash metal and Tang Dynasty after “disco hour,” sometimes broadcasting their own songs and Wang Fan’s hard rock experiments if they could get away with it.

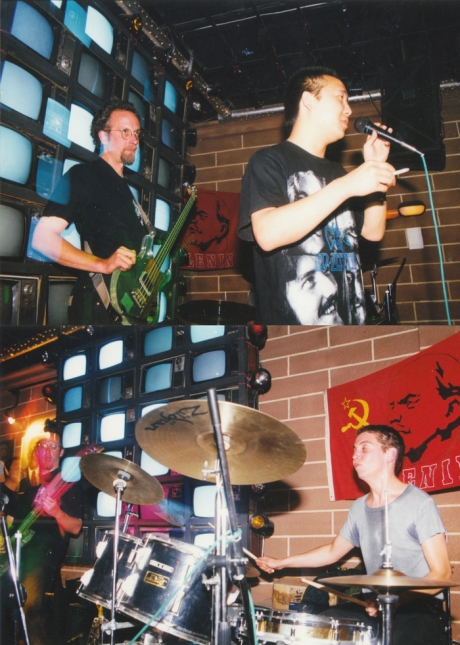

Decay performance at Seahorse Club, 1994

There were virtually no bars explicitly dedicated to live music. The earliest was a small dive called Double Hundred whose stage consisted of a single chair for singer-songwriters. Organized crime was rampant in Lanzhou at the time, and after almost getting shot on one outing to Double Hundred, Yan and his friends never returned. Later, some of Yan’s friends opened a club called Rolling Stone, with the idea to create a venue for their own bands. It wasn’t without its shootings — “the number one saxophone player in Lanzhou was also a mafia; he sent some people to this bar,” Yan recalls — but it did function as both a breeding ground for new ideas and a destination for touring bands. Yan had an eye-opening experience when the Czech-via-San Francisco duo Sabot performed at Rolling Stone. “At that time, I didn’t know post-rock. ‘What’s this… It’s jazz? No. It’s rock? No. It’s… Okay, something strange… That was like a festival. Everybody from every corner of Lanzhou showed up.’”

Yan Jun introducing Sabot at Rolling Stone, Lanzhou, 1998

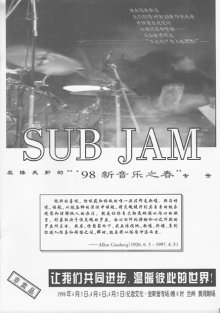

Hungry for more shows of this magnitude, Yan took a more active role as a promoter and organizer in Lanzhou. He found a bar large enough to host a festival, a 1,000-capacity venue dubbed Urban Express. He linked up with a local promoter, who was in the process of booking a Lanzhou show for Cui Jian — at this point, a major star — and they agreed to work together on a festival celebrating Anti-Beijing Rock in rejection of the first generations of Chinese rockers who had progressed to major label deals and stadium tours. The Cui Jian show lost money, so Yan’s “non-Beijing underground rock festival” was cancelled. Not satisfied with throwing away months of work, Yan featured all the bands he’d invited — including No, Tongue, PK14, and a dozen others — in a fanzine with the tagline “Spring of New Music ‘98,” forwarding their demo tapes to Guangzhou-based rocker Wang Lei.

Yan’s advice and Wang’s execution culminated in the Guangzhou Independent Rock Music Festival of April 1998. As the older generation of Black Panther and Tang Dynasty had ossified and become too commercial for Yan and his cohort, the Guangzhou fest was the first clear articulation of a rising movement. Bands like No and Tongue represented a shift from privileged native Beijingers dominating the Chinese rock scene to immigrants from other provinces creating tight-knit communities in migrant villages circling the city, challenging the rock scene’s status quo from the periphery. No’s front man Zuoxiao Zuzhou moved to Beijing from Nanjing in 1993 and quickly became involved in the Beijing East Village avant-garde art collective. Tongue relocated from the far-northwest city of Ürümqi (closer to Kabul than Beijing) in 1997 and took up residency in a squalid one-room apartment in a remote musicians’ commune called Tree Village. Sensing a new energy, a new movement, a new sound — not to mention following a new love interest — Yan moved to Beijing soon after.