As part of their ongoing project to re-issue The Bad Seeds’ back catalogue, Mute Records has unveiled the next three albums in the series: Tender Prey, The Good Son, and Henry’s Dream. These records document a tremendous period of growth for Nick Cave as a songwriter, and as such they are some of the band’s most wildly and excitingly uneven. The first in the series, 1988’s Tender Prey, is a ragged and hungry beast, frothing at the mouth with the sort of murder and mayhem fans had come to expect of a Nick Cave outing, yet the violence is mitigated now and again by the gentle melancholy that the band had been refining since Kicking Against the Pricks. But no discussion of Tender Prey can truly begin without first addressing the album’s titanic opening track: “The Mercy Seat.”

In certain ways, it’s a perfect marriage of Cave’s noise-punk roots and his growing infatuation with melody. At seven minutes and eighteen seconds, “The Mercy Seat” is a dread monolith: a whirlwind of reverb spiraling around Thomas Wylder’s martial drum beat as a lonely Hammond keyboard tolls a single funeral note. Lyrically, it’s Cave’s masterpiece. Once again, the singer draws on two distinct sets of imagery to create an unsettling musical double-exposure. Cave inhabits the mind of a convicted murderer who, in his fits of mad religious fervor, extols the waiting electric chair as the very throne of judgment. In the process, he calls into question the value system that would send a man to his death in the name of justice and puts his own peculiar spin on the age-old quandary of theodicy and personal agency within a Christian worldview. I could go on dissecting the rhetorical effect of the cyclical rhythms, the hypnotic repetition of the central lyric, the way that the strings seem to swell towards climax without ever finding their limit as the song metastasizes towards its conclusion, but really you should just listen to it yourself.

It would be easy to lose sight of the rest of the album after that, but to The Seeds’ credit, there’s still plenty to love once you dig beneath Tender Prey’s surface. “Deanna” is a staple of the band’s live show, a hilarious send-up of fifties doo-wop about a spree-killing couple (or a mass-murdering young lady and the voice in her head, depending on who you talk to). “Watching Alice” is a somber piano ballad (about voyeurism) more assured in its loveliness than any prior Cave composition. The album’s most unexpected pleasure, however, comes at the very end with “New Morning.” It’s a stripped-down gospel hymn that, thanks to some truly beautiful lyrics and the ramshackle early-morning quality of the band’s backing vocals, stands out as a rare moment of unabashed joy in The Bad Seeds’ catalogue.

Some fans and critics regard Tender Prey as the end of a discreet phase of Nick Cave’s career, the last gasp of the junkie prophet crying out in the wilderness before the singer turned to more tuneful endeavors with The Good Son. When viewed in the context of his entire body of work, however, the album’s Gospel-infused balladry seems like a natural outgrowth of the gothic Americana that had informed The Seed’s prior work. And while “The Ship Song” and “Lucy” may reflect a heart-bearing tenderness almost unheard of up to that point, we can’t forget that The Bad Seeds’ albums had been skewing more and more melodic for the last three releases. And it’s not like The Good Son is a record full of lullabies; even under a breezy acoustic love song like “Foi Na Cruz” there’s something sinister brewing. Cave complicates the soothing beauty with a sense of unease through some very subtle piano work and his own nuanced delivery. The darkness and melodrama of his previous work are fully evident in songs like the title track or “The Weeping Song.” The overall result is an album more cohesive than its predecessor, although lacking Tender Prey’s manic highs.

Of the three albums in this batch, Henry’s Dream feels the most like a new start for Nick Cave. It was the first time The Bad Seeds had recorded apart from Flood, who had engineered all five of their previous efforts. It was their first album with former Triffids bass player Martyn P. Casey (replacing the great Kid Congo Powers) and pianist Conway Savage. But the factor that made Henry’s Dream stand out most starkly from its predecessors was probably the involvement of producer David Briggs. Impressed by his work with Neil Young, The Bad Seeds sought him out to bring the ragged, atonal acoustic album forming in their imaginations to life. In Briggs’s hands, however, their stark acoustic vision became the brashest and most rock-oriented record of the band’s early career, a fact that the band still laments. Putting aside any speculation as to what The Bad Seeds’ idealized vision of Henry’s Dream might sound like in Lucien’s audio library of never-recorded works, the album does seem like the runt of the litter. Cave’s flare for crafting sharp, blood-drenched narrative is keen as ever, as evidenced by songs like “John Finn’s Wife” and the outstanding “Papa Won’t Leave You, Henry.” But, except for a few really stand-out tracks (mostly loaded at the front of the album), the music just isn’t as captivating this time around. Whatever its flaws, Henry’s Dream still paved the way for the bolder rock sound that would characterize their follow up, Let Love In, which ranks easily among the finest recordings of Cave’s entire career.

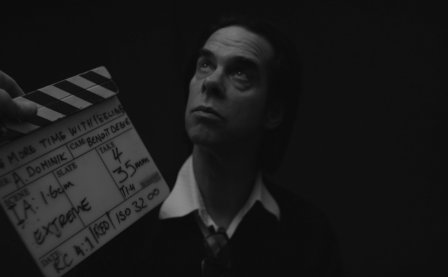

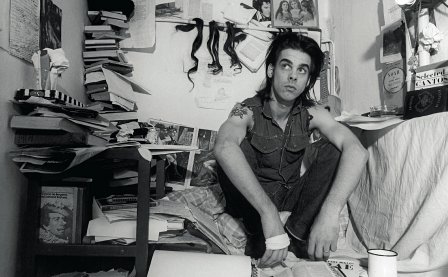

Mute set the bar high with the last batch of reissues, and they’ve remained true to that gold standard. The music is crisper and deeper than ever, and each re-issue comes packaged with a DVD containing a 5.1 surround-sound mix of the album, the b-sides and rarities associated with the particular release, and a segment of Do You Love Me Like I Love You?, a serialized documentary featuring interviews with band members, music experts, and fans relating their memories of The Bad Seeds. My reservations about the documentary remain largely unchanged; it’s a lot of talking heads engaging in, at times, blatant hagiography. See below and judge for yourself:

-

-

Henry’s Dream is worth singling out, however. In addition to the b-sides “Blue Bird” and an acoustic rendition of “Jack the Ripper” (which are already available on the band’s triple-disk B-Sides and Rarities collection), the disk includes five truly excellent live recordings that, to the best of my knowledge, are not widely available anywhere else. Even its installment of Do You Love Me… is eye-opening for the light that the band members shine on the battle of wills that raged during the album’s recording. It’s indicative of the loving craftsmanship that goes into each of these releases, and that obvious respect and affection for the source material keeps me eagerly awaiting every new installment.

More about: Nick Cave, Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds