We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music and films that helped define the year. More from this series

Last year was a surprisingly arty time for mainstream Hollywood. This year wasn’t. Despite the fact that wise-guy Martin Scorsese dropped a remarkably good children’s movie, the majority of 2011 was Hollywood business as usual: remakes, sequels, lurching franchises, and comic book adaptations. Granted, it was also the year of the (relatively) small pro-women’s film like Bridesmaids and The Help that crashed Hollywood’s CGI-machismo party, taking home a sizeable slice of the guests. But neither of those movies are any good (nor on our list), despite their claims to feminism. Which left Hollywood right where it generally likes to be: profitable and dull.

Which also left Tiny Mix Tapes in our most favored position. We young culture writers have noticed the trends, yes, but we’ve responded mainly by eschewing the big stuff (to be fair, we did favorably review Thor and Captain America) in order to keep our keen eyes and ears on what really mattered, on where and how film really thrived: among the outsiders, in fresh forms whose relevance may take time to become clear. The list below is our proof that 2011 can stand beside the best recent years for artistic genius in film, if, as we did, you look carefully.

Perhaps the individual greatnesses of our 25 picks have some common link, a sense of vibrant loneliness that puts them in touch with the modern world. Certainly the big names that appear on our list (Kiarostami, Apichatpong, von Trier, Malick, Almodovar, July) were aiming to define the isolation made real by an ungrounded, frenetic time. But look at the films we’ve noticed that the year all but passed over — Cold Weather, The Four Times, Meek’s Cutoff, Leap Year, William Never Married, Dragonslayer — and ask yourself if the link isn’t just as much a collective, unconscious backlash against Hollywood’s tentpole mentality, a simple need for good films possessed by the times themselves. Maybe all we’re doing is keeping our eyes open. —Alex Peterson

25. The Interrupters

25. The Interrupters

Dir. Steve James

[Kartemquin Films]

Early in The Interrupters, an epidemiologist matter-of-factly states that violence is a disease. He makes a strong case, noting that, like a disease, the best way to stop violence is by changing a population’s behavior. Still, the scientist is a secondary player in Steve James’ stunning documentary. For the film, James documented the fearless members of the Chicago group CeaseFire as they try to stop young people from killing each other. Following the interrupters for a year, James recorded heartbreaking footage of an urban culture where simple disputes can have deadly consequences. The key to the CeaseFire’s success is the simplicity of its message. Members never report any activity to police and at times actually condone gang membership. Because they’re from the street, interrupters can communicate with young people and understand why they feel violence is the only answer. Through simple conversation, CeaseFire create spaces for pause and reflection, which allows any anger to subside. The film was sometimes difficult to watch — there are scenes where families grieve with dignity, and others where young people lash out in chaotic ways — but that was also the film’s greatest strength. It’s also why we think it’s one of the year’s most important documentaries.

• The Interrupters: http://interrupters.kartemquin.com

• Kartemquin Films: http://kartemquin.com

24. Leap Year

24. Leap Year

Dir. Michael Rowe

[Strand Releasing]

February 29 is an especially bad day to die. But in some way, it’s also the most precise. The dead one smiled out of an old photo every now and then, his spirit winking in and out of his daughter’s life — his strength grows throughout the month, and then… nothing, but not a kind of nothing we can put our fingers on or wrap our heads around or metaphorize — a jump discontinuity. Leap Year was brutal in its simplicity and honesty. Laura (Monica del Carmen) was a young woman who worked from home for a newspaper, went out to a club once a week to bring home a guy who wasn’t interested beyond fucking her, and lied to her mother about having friends. When the final lover arrived, we knew it wasn’t going to end well. We suffered flashbacks of In the Realm of the Senses while watching the choking. But the part that really messed us up was the care with which Laura arranged her longed-for final meeting: the incongruity between her sadistic death wish and the love of and for a better-adjusted little brother. Mercifully, Leap Year arrived a year early.

• Strand: http://www.strandreleasing.com

23. The Mill and the Cross

23. The Mill and the Cross

Dir. Lech Majewski

[Telewizja Polska]

In the history of films that insist on not only being art, but on literally diving into it — a history that would include Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams, Robert Altman’s Vincent & Theo, and Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Le mystère Picasso — there has never been so thoroughly dedicated an entrant as The Mill and the Cross, 2011’s Polish answer to the age old question: What are all the peasants in medieval paintings doing on the other side of the canvas? Director Lech Majewski pulled out all the stops with his art director and set designers in order to do a lifesize recreation of Flemish master Pieter Breughel the Elder’s The Procession to the Calvary (1564), and the result is achingly gorgeous. Majewski may well intend his film to be a religious experience too, and whether or not such an experience is had probably depends on the belief system held by any particular viewer (there is no denying the possibility of religious conversion). But you wouldn’t have to be previously curious about medieval painting to be carried away by The Mill and the Cross; its devotion to art is contagious.

• The Mill and the Cross: http://www.themillandthecross.com

• Telewizja Polski: http://www.tvp.pl/filmoteka

• TMT Review: http://tmxt.es/2inh

22. Take Shelter

22. Take Shelter

Dir. Jeff Nichols

[Sony Pictures Classics]

As an examination of the power and control exerted by dread, few films could surpass Take Shelter. Jeff Nichols’ film put contemporary anxiety at the fore, both as psychological event and as a new type of natural disaster. Cyrus (Michael Shannon) struggled to distinguish his apocalyptic visions from the knowledge that he is very likely developing schizophrenia, bringing social and financial ruin on his family in the meantime. The film’s interpretations of catastrophe were various and haunting, as shadowy figures, violent weather, vicious creatures, and ultimately those closest to Cyrus each infiltrated his visions and attempted to undo him. Nichols expertly structured waves of tension, offering only moments of gasping relief before again inflicting Cyrus on himself. Cyrus tested wife Samantha (Jessica Chastain) relentlessly; as she approached a fuller understanding of his demons, she commited as fully as possible to her husband, protecting and supporting however she could. The trust Cyrus demanded was impossible, but Samantha intuited that the only way out of his madness was by going through it. Buoyed by flawless performances from Chastain and Shannon, Nichols delivered a remarkable sketch of what family can mean at its best in such a decidedly exasperating and ominous era.

• Take Shelter: http://www.sonyclassics.com/takeshelter

• Sony Pictures Classics: http://www.sonyclassics.com

• TMT Review: http://tmxt.es/2i35

21. In The Family

21. In The Family

Dir. Patrick Wang

[Self-Distributed]

In The Family, the astonishing debut by Patrick Wang, seemed to appear out of nowhere, but once word got out, its ascent was rapid, earning its director critical love and an Independent Spirit award nomination for Best First Feature. All the more remarkable since Wang had to go it alone for so long. In the face of incomprehension and rejection by producers, festival programmers, and distributors, Wang poured his life savings into financing and self-distributing his film. The plot could have so easily fallen into cliché: a gay Asian man living in the small-town South loses his partner in a car accident and must battle for custody of their son. But Wang, who comes from a theatrical background, employed a restrained yet deliberate style. He was uninterested in the easy cinematic and commercial jolts of sex, violence, or melodrama, and rejected hollow conventions at every turn. What he was deeply invested in was truth, and he told an honest, subtle, and very human story about the dense, bewildering terrain of family, grief, and forgiveness. In an era where glibness is king, In The Family was a quiet revolution, and the work of a remarkably talented director.

• In The Family: http://www.inthefamilythemovie.com

20. The Four Times (Le Quattro Volte)

20. The Four Times (Le Quattro Volte)

Dir. Michelangelo Frammartino

[Invisible Film]

The Four Times, Michelangelo Frammartino’s meditation on the Pythagorean divisions of living matter, initially sounded like the worst kind of filmic indulgence. It had no dialogue and only one human character, a goatherd who staves off death by drinking the dust from the floor of his church. The camera lingered on goats overrunning the land, on a tree engaged in a ritual as old as itself, on charcoal being born; while the film embraced reincarnation with the merest means necessary. But with remarkable patience, Frammartino crafted a thesis on the circularity of living beings that contained the things we recognize and need — humor, loss, fear, celebration — without once tempering his ambition. The film succeeded brilliantly because it ignored artifice. Rather than use mysticism to say something about life, Frammartino used the almost aggressively quotidian to study life’s most essential interactions with itself. In doing so, he revealed both that we all simultaneously share in the earth’s data and that such collisions were rarely bereft of beauty. By couching his film in the isolation of rural Calabria, Frammartino was able to speak to his themes through a nearly fable-like microcosm. Fewer films have ignored modernity so well and found such profound rewards in doing so.

• Invisible Film: http://www.invisibilefilm.com

• TMT Review: http://tmxt.es/2el3

19. Weekend

19. Weekend

Dir. Andrew Haigh

[Sundance Selects]

Glen and Russell hook up after a lonely night at a gay bar. Glen’s comfort with his (homo)sexuality presents itself the next morning as he whips out a tape recorder and eggs Russell on to recount the previous evening for use in an art project. Russell is cowed, but relents and then exposes himself as a romantic: he tells Glen’s eventual audience not that it was a fun random hookup, but that he thought they “were having a really nice time.” This exposed moment reflected director Andrew Haigh’s approach to capturing the brief but intense romance of Glen and Russell, two diametrically opposed modern gay archetypes, played by Tom Cullen and Chris New. Weekend had a naturalistic feel that allowed the viewer to get extremely close to the couple, both sexually and emotionally. Were Glen and Russell pulled to one another because they were genuinely meant to be together, because they were opposites, or because there was a countdown clock on their time together? Haigh didn’t provide a coda explaining what happened after their two days spent together; he simply offered an intimate look at two people who had connected deeply, however fleetingly, an experience that transcended the constructs of film romance, regardless of sexual orientation.

• Weekend: http://www.weekend-film.com

• Sundance Selects: http://www.sundanceselects.com

• TMT Review: http://tmxt.es/2i1r

18. Terri

18. Terri

Dir. Azazel Jacobs

[ATO Pictures]

With such a strong depiction of a boy’s inescapably depressing life, there were moments in director Azazel Jacobs’ Terri that made me forget that it was a work of fiction. At times, the muted color palette, minimal dialogue, and general bleakness made the film feel as if it were shot in a backyard over the weekend. Dust motes from the natural lighting seemed to filter through the screen, and as I watched Terri eating beans and toast on a forlorn sofa, I felt like I was there, or I remembered where “there” was. The unpopular/disfigured/misunderstood teen is a trope that hinges largely on the strengths of the lead and the writers, and in this case, it’s a moon-faced kid with morbid obesity shuffling between school and home in his pajamas, portrayed with aplomb by Jacob Wysocki in his screen debut. But the film wouldn’t have been nearly as memorable without the misfits who latch onto him, including yet another pitch-perfect performance from John C. Reilly as assistant principal Mr. Fitzgerald. Jacobs is really coming into his own as one of our great young auteurs, and with Terri, he created the kind of offbeat charm that attracts a devoted cult of followers, and maybe even some imitators.

• Terri: http://terri-movie.com

• ATO Pictures: http://atopictures.com

• TMT Review: http://tmxt.es/2gbt

17. I Saw The Devil

17. I Saw The Devil

Dir. Kim Ji-woon

[Magnet Releasing]

South Korea has been the forerunner in doing cinematic violence right for at least a decade, finessing its brutality with psychological circumspection, humor, and a poignant sense of despair where others are content to saw their way through one genre film after another. Director Kim Ji-woon’s I Saw the Devil joined the pantheon as a film of eviscerating violence that also succeeded as a probing essay about the degenerative effect of revenge on the human psyche. Choi Min-sik, your favorite Oldboy, returned to the revenge-themed screen to deliver a bone-chillingly triumphant performance as the creepiest of remorseless serial killers ever to make you paranoid about pretty girls going places alone. As his eye-for-an-eye relationship with a victim-turned-vigilante spiraled into spectacular mayhem, we were reminded that vengeance and predation — just like masochism and sadism — can be two sides of the same coin. The film was beautifully shot with a painstaking eye for detail and symbolism that you might not have noticed since you were steeling yourself for the next blow. Cannibalism mirrored the self-consuming nature of obsession, and unquenchable bloodlust proved to be just as hobbling as a severed Achilles tendon. In between gasps and cringes, we were engrossed by a cycle of infliction and retribution that would put the Capulets and the Montagues to shame. Seeing the devil might just mean becoming one.

• I Saw The Devil: http://www.isawthedevilmovie.com

• Magnet: http://www.magnetreleasing.com

• TMT Review: http://tmxt.es/2dw5

16. Martha Marcy May Marlene

16. Martha Marcy May Marlene

Dir. Sean Durkin

[Fox Searchlight]

Yes, this film was about a cult. Yes, it starred Elizabeth Olsen, younger sister of the Full House twins. But those were just details that distracted from the strength of Sean Durkin’s debut feature. I went into the film with arched brow, expecting another closed-room lovefest: Durkin collaborated with indie wunderkinds António Campos and Josh Mond, a Tisch-spawned collective with Cannes and Sundance cred. But this film caught me by surprise, from its cool, tight pacing to Olsen’s steely, jarring performance. An underestimated skill of directors is the ability to align yourself with talent, and Durkin pulled quite a Sofia Coppola here, particularly with DP Jody Lee Lipes (whose name pops up on best-of lists again and again). They worked in tandem, using framing and hard cuts for temporal shifts and flashbacks, wordlessly communicating Olsen’s confusion and terror. She escaped the cult, but remains stunned and somewhat feral, equally entrapped in her sister’s bourgie lake house. Martha Marcy may have been stylized, thin on characterization, and skittish about addressing a world larger than its own confines, but I give tremendous credit to Durkin for allowing the women to dominate this story, making the catty, stiff relationship between the sisters the film’s psychological core. The dark, dark side of the Bridesmaids coin, Durkin’s thriller externalized the terror that lurks in female sexuality, and was a nervy and chilling debut.

• Martha Marcy May Marlene: http://www.iamateacherandaleader.com

• Fox Searchlight: http://www.foxsearchlight.com

15. Bill Cunningham New York

15. Bill Cunningham New York

Dir. Richard Press

[First Thought Films]

Watching Bill Cunningham at work was one of the more wholesome pleasures offered by any film this year. This documentary found the octogenarian constantly on the move, shooting street fashion and society functions for The New York Times, never far from the Schwinn cruiser he used as transportation across Manhattan. A cheerful and lightly rumpled gent, Cunningham clearly relished the fact that, for any of his unassuming yet strikingly dressed subjects, he could just as easily have been a retired hobbyist out on a lark as an icon of the fashion industry. In the film, Cunningham described clothing as “the armor to survive the reality of everyday life,” and indeed he had his own forms of protection: his deceptively run-of-the-mill wardrobe, along with his solitary lifestyle and Spartan living conditions, made him fundamentally enigmatic. But what was there to know beyond what Cunningham wanted us to see? Both through his photography and his life, Cunningham argued that we have the tremendous power to be the arbiters of our own image. Toward the film’s conclusion, there was an unexpectedly moving moment in which director Richard Press attempted to nudge Cunningham into addressing some general impressions of the photographer’s inner life. Cunningham stayed mostly mum, but it was a deeply eloquent, and elegant, evasion.

• Bill Cunningham New York: http://www.zeitgeistfilms.com/billcunninghamnewyork

• First Thought Films: http://firstthoughtfilms.com

14. Dragonslayer

14. Dragonslayer

Dir. Tristan Patterson

[Drag City]

Part art film, part verité doc, part scumbag Laguna Beach, Dragonslayer documents the unfocused vibrancy of a generation that’s struggling to make something meaningful in suburban landscapes of foreclosed homes and empty swimming pools. A skate documentary where instead of ollies the tricks are fatherhood, earning a living, and falling in love — and the injuries are deeper than skinned knees or broken bones — the film followed awkwardly upbeat and infinitely quotable subject Josh “Screech” Sandoval through a brief but transformational period in his life in Fullerton (the real OC), as he reentered the skating world after a bout of depression, hooked up with a longtime crush, and learned how to be a father, sort of. Plus, lots of cheap beer, drugs, and trespassing. Visually, Dragonslayer was absolutely off the hook, pirouetting between restrained realism and gorgeously indulgent abstraction with a gritty, oversaturated grace that was as memorable as Sandoval’s weird-ass skating style. But as first-time director Tristan Patterson documented his subject’s stumbles, the director’s emotional pallet proved to be even more nuanced than his aesthetic one. In lesser hands, Screech Sandoval might have merely been one of cinema’s most iconic slackers of all time. Patterson’s feat was in showing us his subject’s ambition.

• Dragonslayer: http://dragonslayermovie.com

• Drag City: http://www.dragcity.com

• TMT Review: http://tmxt.es/2irq

13. Cold Weather

13. Cold Weather

Dir. Aaron Katz

[IFC Films]

Cold Weather was an aptly titled film. About an ex-forensic science student and Sherlock Holmes enthusiast living with his sister in his hometown of Portland, OR, this film hunkered down and moved slowly. We’d worried that mumblecore had flared out before delivering on its promise. While Aaron Katz’s film didn’t sting us like Beeswax did, it had the advantage of a couple of unique pleasures. The first: the main character got a job in an ice factory. The second: he embarked on an amateur investigation into an undermotivated and underexplained mystery involving his ex-girlfriend. Most of the film’s charm — and it ran on charm — was in its economy of movement. We were happy to wait while the characters established themselves (in greater or lesser depths). When the action got underway, it was easy to follow; it didn’t get our adrenalin coursing any more than it drew blood. This made the final scenes that much more joyful. While blazing glories had long left us cold, the conclusion of Cold Weather kindled in our breasts quiet warmth.

• Cold Weather: http://coldweatherthemovie.com

• IFC: http://www.ifcfilms.com

• TMT Review: http://tmxt.es/2drv

12. Rubber

12. Rubber

Dir. Quentin Dupieux

[Canal+]

Michael Bay’s robotic porn series Transformers has earned over $2.5 billion worldwide, enough to purchase 50,000 private islands. But when the most open-minded film lover hears about a move where a tire comes to “life” and uses telekinesis to blow up heads, he or she wants nothing to do with it. Indeed, Rubber was a beautifully shot horror-comedy with a concept that was predictibly passed off by the general movie-going audience. For the rest of us lucky enough to see Robert, the name of the tire, roll through the California desert, we experienced satire at its finest. From hearing the plot and viewing the trailer, one may have expected a B-movie with bad acting and fun-filled gore. But while there were plenty of laughs and over-the-top violence, director and writer Quentin Dupieux gave the audience even more by breaking the fourth wall, including a side plot of binocular-wielding on-lookers watching the film take place in real-time. The commentary on Hollywood movies was purposefully spoon-fed to us while possibly unintentionally distracting the viewer from the actual craft of poignant filmmaking that unexpectedly took place. Rubber didn’t break new ground, but it undeniably treaded down a rugged path of creative ingenuity.

• Rubber: http://www.rubberthemovie.com

• Magnet Releasing: http://www.magnetreleasing.com

• TMT Review: http://tmxt.es/2ef8

11. Certified Copy

11. Certified Copy

Dir. Abbas Kiarostami

[IFC Films]

The setup itself was already uncharacteristic for an Abbas Kiraostami film, since it almost perfectly embodied the stereotype of the European import. Set in Tuscany, Certified Copy starred Juliette Binoche as an antiques dealer who encounters an art historian and lecturer, and spontaneously ends up spending the day with him. The pair proceed to exchange a steady stream of ideas about art, philosophy, and life… in other words, your standard arthouse fare. In its first half, Kiarostami proved himself quite adept at making this type of picture, almost playing out like a Before Sunrise for the aging academic set; relaxed, beautifully written and photographed, and consistently engaging. But it’s in the second half that the film ventures into truly unchartered territory, morphing and distorting itself in a way that I’ve literally never encountered in a movie theater before. Mind you, Certified Copy isn’t the type of gimmicky exercise in jigsaw mindfuckery that requires being “worked out” (à la Inception), although it could easily be viewed that way. I prefer to experience the film as a dizzying disquisition on the nature of relationships themselves, a film that viewers ought to savor and luxuriate in, rather than attempt to decipher or decode.

• IFC: http://www.ifcfilms.com

• TMT Review: http://tmxt.es/2dau

10. William Never Married

10. William Never Married

Dir. Christian Palmer

[Burning Ladder Films]

Christian Palmer is a singular new voice in American cinema, and it’s hard not to resort to an overabundance of superlatives when trying to describe how William Never Married established itself as such an indelible and entirely new kind of film. So I won’t even try not to. Palmer and his small crew in Seattle wrought this masterpiece with a very limited budget and the desire to turn one of the most basic kinds of stories into something completely fresh and unnervingly compelling. Palmer starred as the titular William, a budding alcoholic and obsessive young man constantly hindered by his mother’s late-stage alcoholism. Using the assured camerawork of R.K. Adams and virtuosic editing skills of both Ian Lucero and Palmer to impart just as much meaning to the film as the naturalistic and painfully awkward dialogue (which will hopefully become a trademark of this creative team), WNM embodied a gripping sense of sustained and virtually limitless loss that was as beautiful/disturbing as it was devastating. We feel altogether confident in asserting that William Never Married will maintain a pride of place among American tragicomitragedies.

• William Never Married: https://www.facebook.com/pages/William-Never-Married/120391067935

• Burning Ladder: http://www.imdb.com/company/co0277165

• TMT Review: http://tmxt.es/2d6s

09. Drive

09. Drive

Dir. Nicholas Winding Refn

[Film District]

Following last year’s undervalued Valhalla Rising, a tone poem of sheer brutality and epic myth-making, Nicholas Winding Refn further sated his appetite for the offbeat undercurrents of machismo with the more nuanced, narrative-based Drive. Tapping into the zeitgeist’s appropriation of all things 80s, Drive exhibited a retro-chic as effortlessly smooth and precise as its driver behind the wheel; its sheen of neon-pink font upon the dark, quiet streets of L.A. coupled with the pulsating rhythms of its remarkable score, an enrapturing combination of Italo disco beats and minimal synth pop, created an atmosphere that was both familiar and alien. But Drive’s true greatness came once it peered beneath the veneer, revealing a shy stunt car driver who just wanted to do the right thing in a violent world where honor and trust sign your death warrant. Refn’s channelling of Jean-Pierre Melville by way of Walter Hill yielded a brilliant balance of minimalism amid broad gestures, where action punctuated the drama rather than drove it (no pun intended) and the tension between big moments exuded a surprisingly tender humaneness, especially in its awkwardly touching love story. The film’s ability to successfully blend both genuine emotion with artifice and tenderness with extreme tenderness made it one of the year’s most unique and satisfying experiences.

• Drive: http://www.drive-movie.com

• Film District: http://www.filmdistrict.com

• TMT Review: http://tmxt.es/2hsm

08. The Skin I Live In

08. The Skin I Live In

Dir. Pedro Almodóvar

[Sony Pictures Classics]

By now, it’s almost a cliché to put a Pedro Almodóvar film on a year-end list. True, his last few movies may have been “disappointments,” a little too self-referential and cycling back onto some of his earlier films. But The Skin I Live In spoke more to the level of his output from Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown to Talk to Her than anything else. With this film, Almodóvar took a familiar trope, the mad scientist obsessed with revenge, and transformed it through his inimitable style of absurdist melodrama. Sure, he similarly featured Antonio Banderas kidnapping a young woman in his 1991 film Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!, acting as a subversion of the traditional role of the psychopath. But this time, Banderas’ Robert Ledgren was a less ambiguously twisted madman, yet his performance through the sinuous narrative ensured the audience would sympathize with his motives. Almodóvar’s interest in the human body and the questions of sexual identity felt somehow more at home in this one-off amalgam of science fiction and captivity horror. Whereas in the past, he might have inserted surrealist touches, à la Buñuel, to push the viewer’s visual conceptions of what it means to be flesh, The Skin I Live In intrigued us by literally grafting it on, piece by piece.

• The Skin I Live In: http://www.sonyclassics.com/theskinilivein

• Sony Pictures Classics: http://www.sonyclassics.com

• TMT Review: http://tmxt.es/2i8l

07. Bellflower

07. Bellflower

Dir. Evan Glodell

[Oscilloscope Laboratories]

Bellflower, Evan Glodell’s directorial debut, told the story of two best friends, who, in the most blatant display of dudeness, spent their days consuming beer and bacon for breakfast and preparing for the future by building a badass muscle car for what they hoped to be the impending apocalypse. The film’s weird combination of Mad Max and mumblecore, not to mention its peculiar use of homemade cameras and moldy lenses, could very well have resulted in a messy ordeal. However, with dexterity and sensitivity, Glodell crafted it all into an enraged, energetic story about coming to terms with adulthood while the anarchic energy of youth still just wants to burn it all down. All of this was strengthened by Jonathan Keevil’s hauntingly beautiful soundtrack, whose theme song was nothing short of an anthem for the frustrated dreams of youth. Bellflower dealt with that tragic moment when we finally realize that, no matter how angry and resentful we may be, not everything in life can be fixed with a flamethrower. In a decade where indie cinema has come to mean an endless and repetitive flow of quirky characters in cute love stories coated with indie rock soundtracks, Bellflower could very well be the fiery salvation we’ve all been waiting for.

• Bellflower: http://www.bellflower-themovie.com/home

• Oscilloscope Laboratories: http://www.oscilloscope.net

• TMT Review: http://tmxt.es/2gwa

06. Love Exposure

06. Love Exposure

Dir. Shion Sono

[Omega Project]

Writer/Director Shion Sono’s roughly four-hour-long epic about religion, obsession, perversion, the finer points and practice of upskirt photography, and the innate allure of purity knocked our socks off. Shot in an astounding three weeks and imbued with the same visual and narrative inventiveness that brought him worldwide attention 10 years ago (2001’s The Suicide Club), Love Exposure was an oddly touching and perversely (ha!) joyful experience. Perhaps owing to the crunched shooting time, this movie’s frenetic pace mitigated its gargantuan runtime, and when all was said and done, we were introduced to some of the most compelling characters to arise from the cinema in recent memory. Yu Honda’s single-minded, almost daft obsession with finding a modern version of the Virgin Mary to marry was never lampooned. And far from serving as a mere exemplar for Sono’s brutal social insights (as so many characters in this director’s other films have), Yu’s struggle to find something pure is treated with a positively Rublevian level of compassion on Sono’s part. Plus, it was undeniably entertaining and downright hilarious in parts, and definitively redefined the way boners in sweatpants should be filmed.

• Love Exposure: http://www.ai-muki.com

• TMT Review: http://tmxt.es/2f99

05. Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives

05. Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives

Dir. Apitchatpong Weerasethakul

[Strand Releasing]

Leaving his traditionally bifurcated structures behind, Apitchatpong Weerasethakul plunged even further into the realm of tropical surrealism, tapping into parallel realities and past lives with a delicate restraint that was all his own. There may have been a talking catfish and laser-eyed monkey ghosts, but these were fantastical only in theory. Onscreen, the abstractions were merely an extension of the mundane reality of Uncle Boonmee slowly fading from existence. The tropical setting, a mainstay for Weerasethakul’s films, once again provided a perfect locale for the director’s melding of animism and the mystical, the material and the spiritual, and the ordinary with the otherworldly. Boonmee operated on its own internal logic, modestly inviting the viewer to enter its world on its own terms, never offering any guidance through traditional narrative structure or action. Instead, Weerasethakul blurred the line between past and present, living and dead, and man and nature to achieve a remarkable spirituality that retained its quixotic, enigmatic form as it dealt, quite touchingly, with memory, death, and lost love.

• Strand: http://www.strandreleasing.com

• TMT Review: http://tmxt.es/2dq3

04. Melancholia

04. Melancholia

Dir. Lars von Trier

[Magnolia]

How can one convey devastation? You can’t cry enough. You can’t scream enough. And you suddenly remember how comfortable boredom was. With Melancholia, we desperately shored up our aphorisms and metaphors like armchair embraces from phantom limbs. We went and paid to feel ‘more-than’ for a couple hours, basked in the vulgar rendering and sour aftertaste of countless bubbling milky melodramas. And then, all of a sudden, it was no sinking feeling, but a pure red-eyed state of fixed attention on the end of the fucking line. Exhilaration never felt so —— AAAAHHHHH!!! All because of yet another movie. A resplendently photographed depression-case stinkbomb designed to hurt. How could I possibly praise Melancholia as a distraction? I don’t need to. People will see it, and they will be affected if they can get past the unpleasantness (us Bergman and Cassavetes folk have a leg up). To what end you say? To the end. Somebody went and made a truly satisfying tome about it. There was a refreshing freedom in the harshness employed here. Whatever Roland Emmerich might think, no one need take in this subject in a well-rounded, side-road-providing way. It surely won’t be taking you in this fashion.

• Melancholia: http://www.melancholiathemovie.com

• Magnolia: http://www.magpictures.com

• TMT Review: http://tmxt.es/2gxm

03. Meek’s Cutoff

03. Meek’s Cutoff

Dir. Kelly Reichardt

[Oscilloscope Pictures]

With her fourth feature and first period piece, Kelly Reichardt maintained her position as a major talent in American cinema with Meek’s Cutoff. She and writer Jonathan Raymond applied the stark aesthetic of their previous collaborations, Old Joy and Wendy and Lucy, to a frontier tale that refused to settle into conventional rhythms or permit easy identification with its characters (played, without a trace of egotism or self-consciousness, by a small cast led by Michelle Williams and an almost unrecognizable Bruce Greenwood). Instead, the snatches of overheard dialogue and shots of pioneers dwarfed by desolate landscapes was like peering through a peephole at the Oregon Trail in 1845. Meek’s Cutoff was a demanding film — it risked boring audiences, and in many cases, it did. But patient viewers were rewarded with a rich experience that built tremendous intensity as it progressed. By the ominously uncertain finale, the film’s title had assumed endless and paradoxical meanings involving power dynamics and sudden endings and divergences. With mythical, Biblical suggestiveness, Meek’s Cutoff placed Manifest Destiny within the whole history of human hubris and greed, but this haunting film’s avoidance of nostalgia and anachronism made its sexual, racial, and political implications all the more powerful and complex.

• Meek’s Cutoff: http://meekscutoff.com

• Oscilloscope Pictures: http://www.oscilloscope.net

• TMT Review: http://tmxt.es/2er3

02. The Future

02. The Future

Dir. Miranda July

[Roadside Attractions]

Miranda July certainly took her time to present us with a new feature film, and, love it or hate it, The Future was filled with all the eccentricity one has come to expect from a filmmaker who manages to stir bouts of rage and cries of praise in equal measure. Paw Paw, a soon to be adopted stray cat, was the improbable catalyst for the personal crisis that will have the thirty-something couple Sophie (Miranda July) and Jason (Hamish Linklater) delve into a bizarre personal journey once they’re faced with the fear of the responsibilities that the new animal promises to bring. Despite the typical July cuteness (there is a narrating cat, after all), The Future had a remarkably different tone than her 2005 debut (Me and You and Everyone We Know), constructing itself as a far more serious, darker, and grimmer experience. The director’s mannerisms here all seemed to serve a higher purpose and did a great job of conveying the film’s central conflict between the desire to fully explore life and the inevitable anguish of being confronted with such overwhelming freedom. The Future certainly made for a bleak and cerebral experience, and if you could look past some of the annoyances and excessive quirkiness for which July has come to be known, you’d find one of the most thought-provoking and narratively ambitious films released this year.

• The Future: http://thefuturethefuture.com

• Roadside Attractions: http://www.oscilloscope.net

• TMT Review: http://tmxt.es/2go5

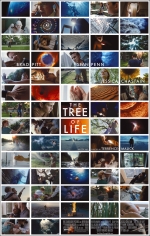

01. The Tree of Life

01. The Tree of Life

Dir. Terrence Malick

[Fox Searchlight]

Like many filmmakers, Terrence Malick likes to ask big questions. But unlike most of his contemporaries, he’s really, really upfront about it. A major proponent of voice-over narration, the director often layers the voice of one or more characters over a montage of fleeting events, a life in constant motion, eschewing conventional exposition to present human beings in uneasy transition. And in The Tree of Life, Malick made a grieving Mother (Jessica Chastain) whisper, “Who are we to you? Answer me!” as we watched a scientifically accurate rendering of the formation of the cosmos. At that point, it was enough to make a lot of people walk out of the theater. Maybe they hadn’t seen Malick’s other movies, which are some of the most palpably transient narrative films ever made, where moral uncertainty is always ameliorated by spiritual harmony, emphasizing the preciousness of moments when perspective is still open-ended. Or maybe they realized this wasn’t just some movie about a family living in 1950s Waco, Texas.

Indeed, though they took up most of its running time, The Tree of Life wasn’t entirely about the O’Briens; their surname isn’t even mentioned in the movie. In fact, we only learned where they live about halfway through the film, labeled on the side of a moving truck, spraying clouds of DDT over neighborhood lawns, a dozen children dancing and laughing in the white smoke. It’s one of many images in the film both ethereal and unsettling, not just because of its aesthetic rush, but because of the fantastical images that immediately preceded it: a boy hiding in an empty grave, a mother laid to rest in a glass casket in the middle of the woods. The reciprocation of life and death, of memory and imagination, are hardly new themes for Malick, but they were never as variegated or as fluidly depicted as they were here. In his fifth film, the director gave us not just another celebration of human experience, but a thoroughly detailed, impressionistic, uncanny portrayal of how that experience forms into long-term knowledge, often transcending it in the process.

By elevating one man-child’s story to cosmic proportions, Malick’s film was so thoroughly, unabashedly self-absorbed that it dared us to return to childhood ourselves. It recreated a time when one sees and hears many things, mostly forgotten or saved unconsciously to rediscover later. In miming this process, Malick began with an explanation of the ways of grace and nature, only to transmit them through various voices and guises, splintering and interweaving through long, often fragmentary sequences. With aggressive and elliptical editing, Malick created a dialogue of associative imagery: certain characters appear for minutes or mere seconds, or hang in the background as if in peripheral vision; many small incidents occur that occasionally seem plucked from whole other movies themselves. It’s almost fitting that the film ends stumbling through the gates, ladders, and paved paths of an alternate reality — Malick’s first foray into the supernatural — threatening to derail everything that came before it. (As if the rest of the film wasn’t set on confronting objective reality.)

By interrogating the universe, The Tree of Life proved to be Malick’s most profoundly anti-cynical and vulnerable film yet, a combination that doesn’t sit well in our increasingly self-conscious, jaundiced culture. As a result, no other film this year was as fiercely debated or scrutinized. Yet the film stood out in an incredibly strong year for movies overall, not simply for its ambition, but for its generosity. At once kaleidoscopic, personal, and unhinged from convention, Malick’s unwieldy epic consistently rewarded our imaginative sympathy.

• Tree of Life: http://www.twowaysthroughlife.com

• Fox Searchlight: http://www.foxsearchlight.com

• TMT Review: http://tmxt.es/2g7u

[Artwork: Keith Kawaii]

We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music and films that helped define the year. More from this series