Although it’s almost entirely inconsequential, The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel maintains throughout its lackluster runtime precisely one stirring aspect, even if it stirs in exactly the wrong direction. The movie uses the entire country of India as its own Magical Negro, bypassing the worthy aim of capturing (photographically or script-wise) the beauty and culture of the subcontinent in favor of using it to guide a passel of bored English gentlefolk towards some peace in their twilight years.

The Magical Negro, a cinematic trope identified by Spike Lee, is a perennial pop panacea: the dark-skinned quasi-mystic who lends his soulful ear and sage words to a white person in trouble. The most prominent examples are Morgan Freeman’s Red in The Shawshank Redemption, Scatman Crothers’ Hallorann in The Shining (the Magical Negro pops up a lot in Stephen King works), and Djimon Hounsou in In America and Gladiator. Too many filmmakers look for a narrative shortcut in their reliance on conflicted, neurotic white characters who believe in the myth of some mysterious, pure wisdom coursing through other races — people who can remain true to themselves (and by extension, their culture) rather than be led astray by society’s evils. Here we have a horde of neurotic whites nursing at the wisdom-teat of an entire nation’s worth of dark-skinned people. Undoubtedly, whole countries have been substituted for a single Magical Negro before (Under the Tuscan Sun? The Piano?) but perhaps never with such weightless results.

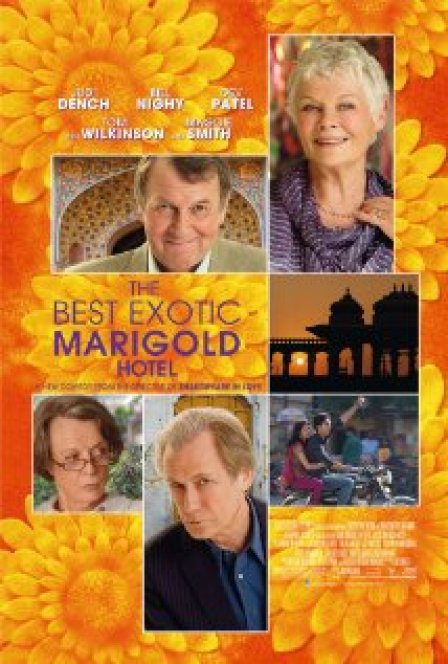

Actors Bill Nighy, Tom Wilkinson, Maggie Smith, Judi Dench, and a handful of less recognizable pros have been assembled to play discontented old Brits settling into a charmingly run-down old folks’ home in Jaipur, India. Ostensibly, they’ve come for an alternative to the hell of retirement in gloomy England; in actuality, they’re looking to receive the healing power of the cute Indian culture they didn’t know they’d been missing. Everything’s a joke on aging, fusty English manners, or the gastronomical effects of Indian food until, inevitably, each of the retirees begin to realize that India really does have the ability to lend them a new lease on life, at which point late life lessons are served up en masse.

Nighy and Wilkinson — as a retiree who invested his savings badly and a homosexual court magistrate, respectively — make the most out of their roles. Both actors are blessed with the ability to play crap material gamely while giving the impression that they’re in on the joke. Nighy is an ace at conveying ironic distance from sub-par scripts (witness Wrath of the Titans and Wild Targets, for two recent examples), and Wilkinson, a great actor, lucks out in Marigold by landing the only character whose problems convey a real interest in India (he’s searching for an Indian man who holds a long-lost connection to his youth).

Smith and Dench — as a wheelchair-bound former servant and a widowed housewife, respectively — are each more than enough actress to handle the schlock with which they’ve been saddled (Smith spends the movie gradually easing out of her lifelong racism by gradually developing an appreciation for the hard work done by India’s Untouchable caste). But both make the mistake of going for the kind of gravity usually reserved for Shakespeare or Ibsen — acting that seems ridiculously unnecessary when it’s reduced to portentous speeches about the nobility of the underclasses or the best way to dip a biscuit into tea.

As you might guess from the trailers, things more or less work themselves out for everyone involved, and India remains as placid an imaginary playground as it ever was in a movie that didn’t care about it at all. But it doesn’t follow that movies aimed at an older demographic should be more simplistic, and there’s no way that Baby Boomers have greater tolerance for tired tropes like the Magical Negro than do the rest of us. That generation grew up on movies from the 50s and 60s, which were the days of Melville, Mann, Godard, and the late, great work of Renoir and Hawks. Marigold, though, plays to more conservative tastes that themselves don’t justify the kind of derivative stereotyping the film practices. Like The Bucket List, it’s another generic parade of irascible, shockingly foul-mouthed, and wizened geriatric stereotypes — a film that treats the elderly and the dark-skinned like sketches on a drawing board while raising the narratively damning question of why they decided to put older people front and center in the first place.