Aspiring novelist and sometime critic David Harris (played here by David Schonfeld) sits down to watch Brand Upon the Brain!, the story of director Guy Maddin (played as an adult by Erik Steffen Maahs and as a child by Sullivan Brown) in a recollection that the director claims is 97% true. Earlier that day, the writer found a cat that had been savaged by coyotes in his front yard. He lives in a city, and the prospect of coyotes is both puzzling and enthralling. After viewing Maddin’s film, Harris dreamt that night of coyotes.

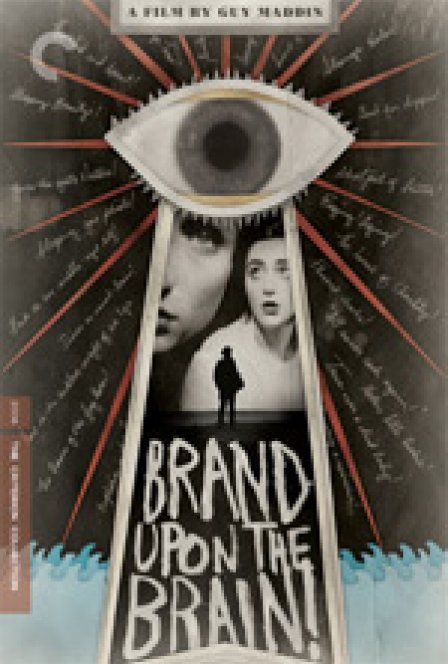

What if you could choose the voice that narrates your own life? Would it be the husky rococo throat of Isabella Rossellini? How about the neurotic ticking of Crispin Glover? Maybe it would be the age-ravaged tongue of Eli Wallach. Or it could be the director himself, Guy Maddin, narrating as his adult half returns to the island where his parents kept an orphanage. He has been charged to repaint the lighthouse at his dying mother’s behest. Imagine our writer Harris in a Sublime shirt waiting to be stained that evening with mustard oil, remote in hand, desperate to hear all of the seven voices and only able to select one. He chooses Glover. But as the film is divided into chapters, he gives each of these celebrities the chance to speak.

Unlike Maddin, Harris did not grow up in an orphanage. His mother did not sit in the lighthouse tower, scouring the island like the Eye of Sauron, in search of misbehavior and sexual transgressions. His parents were open about sexuality. Unlike Maddin, Harris grew up on a farm with adopted parents. They kept an octopus and a cockatoo for pets. But his father, unlike Maddin’s, did not practice nightly experiments, sapping the nectar from the brain stems of the orphans to make his mother young again. As Harris remembers his childhood, it’s not in silent film tropes. There is no orchestra. There are no title placards. Laurie Anderson does not narrate. The memories come more in waves of feeling. Like Proust, a taste or a scent can transport Harris (and it seems Maddin as well) to our 97% true childhood realms. That clichéd madeleine is much more powerful than one thinks.

First, unrequited love still haunts the grown-up Maddin. As his mother dies in his arms, the nude phantom of a childhood crush steers him away. As Harris tries to rest in his bed, visions of coyotes and chaos preventing our writer from sound sleep, sometimes his first loves return, hover over the bed, and prevent him from resting soundly. Unlike Maddin, there is no question of gender. He cannot recall a boy-crush. Even with a gay brother, there is no gender confusion, no cross-dressing (except for Halloween). Yet just as young Maddin sees women kiss women, young Harris has seen men kiss men. In both realities, this seems just fine.

The idea of mother always looms large. Maddin, enslaved to his mother’s moods and whims, rushes home whenever he is called to dinner. Mother so desperately wants to be young again, but rage makes her old. Harris, unemployed for the first time in adult life, could be satisfied with his current situation. But he has learned that employment equals self-worth. Mother will not be pleased. It feels like the time Harris lost his way in the woods one December. He wandered too far from the farm as he pretended to track a puma. The whiteness blinded him and as the delirium of hypothermia set in, the spirit of his departed grandfather guided him from those dark woods onto a highway. Three cars passed before someone bothered to stop and rescue the frozen child.

It’s shame that carries the most weight. Even as Maddin’s mother returns to her beloved isle, blind and feeble, the burden of the past cannot be forgotten. There is no more brain nectar to be had, and age has finally caught to her. But can Maddin forget her desperation? Like a coyote, she devoured his childhood friend, so fraught with the fear of wrinkles that she would consume the life force of another. Harris’ mother never did such a thing. She only got a facelift.

Ninety-seven. That sly number that equals what’s true. What is true and what is fake? Is memory anything other than an invention? Like all else, the coyotes will fade into time; only the residue of an emotion is bound to remain. Maybe that disemboweled cat will become a small dog. Maybe Harris will remember finding it in the evening, rather than walking home carrying his lunch. But as he delves deeper, scenes from his childhood melding with fiction and becoming his novels, does this fusion make his art, Maddin’s art, any less worthwhile? The destruction of that line, the division between fiction and truth, brings us closer to reality. That’s what Maddin wants us to see all along.