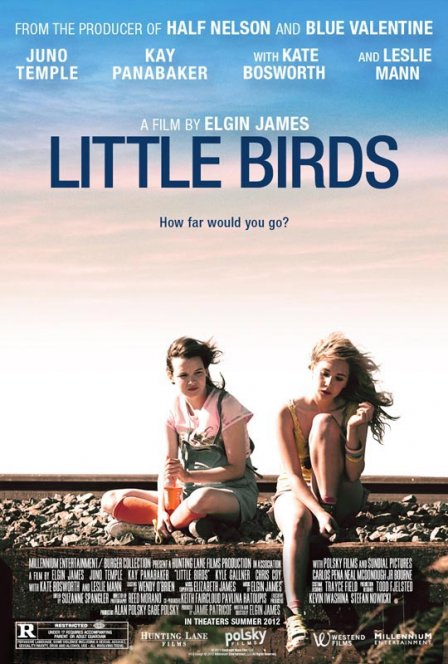

Bleakness and simmering violence are two primary moods of Little Birds. In between these extremes are tones of somber reflection and a lust for adventure, but underlying sadness and startling acts of aggression are what you will remember. I’m telling you this ahead of time so you won’t be alarmed when the film becomes physically uncomfortable in its predictability, a downward spiral of snuff that will likely make you wince.

Little Birds begins in a bathtub with a naked teenage girl (Juno Temple as Lily) examining self-inflicted cuts on her thigh. While she submerges herself, a voiceover from her friend Alison (Kay Panabaker) describes how Lily wants to drown in the toxic shallows of the Salton Sea. Polluted by agricultural runoff and banked with carrion and dead fish, the Salton Sea (technically an endhoreic lake basin) is an apposite setting for a story about internal desolation and the desire to abscond. Lily and Alison have unfulfilling home lives, but their friendship is really borne out of convenience and boredom, and these constants are ultimately what compel them to leave. They don’t need to flee, but when Lily meets a skater from Los Angeles she feels an irrepressible urge to get away from their proverbial hellhole. Impetuous and manipulative, she guilt trips Alison into stealing a truck and driving out to Los Angeles to meet up with her Casanova, who lives in an abandoned motel in Echo Park with his two worthless friends. Young and innocent as they are, the girls idealize the city and its escapist possibilities, yet they’re blind to the nihilism and recklessness of their gutter-dwelling acquaintances.

Although its overarching theme of innocence lost is typical, the story behind this story is a stirring one. Writer and director Elgin James is a product of the Sundance Institute’s Screenwriters and Directors Labs, but before that he was homeless and affiliated with gangs in Boston, so the senseless violence depicted in Little Birds is rooted in reality. A criminal for more than a decade, James has said that art house cinema was a refuge when he was embroiled in lawlessness. But while providential encounter with producer Jamie Patricof helped him find his footing and led to the creation of this film, knowing this doesn’t change Little Birds’ tone, which vacillates between intimate and stagy, as unassured as its protagonists.

The adults are particularly weak in their roles, and though we can see Lily’s detachment from her mother (Leslie Mann), the emotional distance being portrayed comes off like a rehearsal. Juno Temple plays the bitchy daughter effectively enough, but Leslie Mann is terribly miscast. Known for her comedic support in everything Apatow, Mann is unable to summon the well of distress that’s needed to be convincing. It only made me recall Holly Hunter’s impeccable turn as a distraught single mother in Thirteen, a film that Little Birds will inevitably be compared to. On a similar note, Alison’s father (David Warshofsky) literally does nothing. He sits in an armchair and interacts with his daughter once or twice, and it’s unclear if he’s an invalid or just depressed.

While the two halves of Little Birds are somewhat incongruous, the through-line of the story holds it together, and I will say that it leaves its mark. The tension that builds as the girls spend two days drinking and prowling is more than palpable — it’s confrontational. Perhaps too much so. I could imagine some defiant teenagers latching on to this movie, stridently identifying with Lily’s vociferous angst, but it misses the balance between grittiness and commiseration that we have seen in better films of this ilk. For its last half hour, I felt nothing but queasiness.