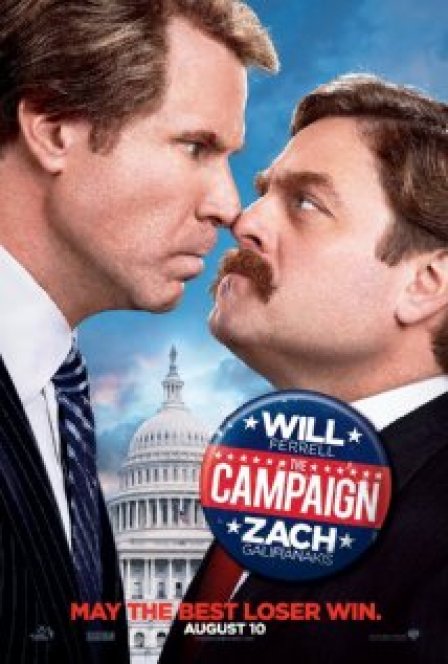

Will Ferrell has never had trouble finding comedy in incompetent politicians talking themselves into trouble by going off-script. So far he’s seemed content to release his wacky political impersonations in self-contained little chunks, but 2012 appears to be the year he’s decided we need to see one of his lambastings in feature length. After years of nailing George W. Bush in short form, on both SNL and in his own comedy specials, Ferrell has broadened his scope with The Campaign, a would-be satire on American politics whose crowning achievement is simply attempting something a little grander than cheap laughs.

Not that there are no cheap laughs: when a Ferrell film is given an R-rating to work with, the jokes tend to be so gloriously cheap you can’t help laughing, but here they’re precisely what cost the movie the successful satire it seems to have been aiming for. In The Campaign Ferrell plays Cam Brady, a corrupt, dim-bulb of a congressman who releases his own sex tape as a campaign ad promoting himself, honestly believing it will pump his numbers. Two contemporary political mainstays ripe for skewering have been forged together in hopes of pulling off one killer joke, but it’s so ridiculously over-the-top that it cancels any of the subtlety that satire requires.

Brady — a free-for-all mix of Mitt Romney’s over-coiffed, foot-in-his-mouth woodenness and Bill Clinton’s rabid, insouciant libido — is a Democrat used to running unopposed in his North Carolina district. When a pair of billionaire industrialists named Wade (Dan Aykroyd) and Glenn Motch (John Lithgow) decide that North Carolina is the perfect place to implement a money-making scheme involving bringing Chinese labor to the US, they plot to oust the scandal-prone Brady and replace him with a Republican puppet candidate. They find their man in gentle-soul rich kid Marty Huggins (Zach Galifianakis), a born loser in every sense except that his father (Brian Cox) is a powerfully wealthy Southern gentleman with a chubby finger in politics. Basically playing a broader version of the brother Seth that he uses in his stand-up, Galifianakis at first pitches Huggins as an earnestly innocent patsy, but, as is often the case with Galifianakis characters, he reveals a well of bottled, uncontrollable (though no less dumb) anger when Brady starts the nasty campaign tactics.

The Motches — over-obvious riffs on the Romney-supporting, billionaire Koch brothers — are played as the kind of pollution-loving, poor-people-hating corporate villains you might see on an episode of Captain Planet, obscuring the controlling role that money plays in the American political system. The Motches aren’t a total failure, however. While it’s often a bit confusing that the movie’s Koch stand-ins are actually working to bring down a character partially modeled on Romney (Brady), the conflict does lead to the movie’s best running joke, in which the all-powerful billionaires scramble to redirect their tactics every time their political puppets reveal themselves to be too dumb, hard-headed, or naive to act as expected. If The Campaign has anything to say besides that it thinks fat people, the word “pussy,” and Republicans are funny, it’s that no amount of lobbying can stop politics from being interesting, primarily because of the essential unpredictability, or maybe just the sheer arrogance, of politicians.

Unpredictability and arrogance have always been the mark of Ferrell’s comedy; his most popular characters invariably poke fun at some form of blustery masculinity. But Ferrell’s unpredictability is generally aimed at much simpler targets than the slipperiness of meretricious politicians: for laughs he mainly relies on phrases slung out of left field, absurdist interjections that are consistently funny (“Staple my balls to my nipples and do situps this is painful!” Brady screams after being bitten by a snake) but that just as often distance us from any notion that the character he’s playing might resemble a human being. This is the big problem with The Campaign: Ferrell’s humor is at odds with political satire, because for satire’s social critique to work we need to at least believe its humor is connected to the real world.

Like Sacha Baron Cohen, whose recent, similarly wide-aiming political satire The Dictator was a better, sharper movie because of its greater willingness to take its premise into dark territory with or without the promise of safe return, Will Ferrell (and the film’s writers, Chris Henchy and Shawn Harwell) refuses to steer clear of a good joke, even at the expense of narrative cohesion. To his and director Jay Roach’s credit (and this is high-praise for a Will Ferrell movie), no joke in The Campaign is allowed to digress so far that the plot is forgotten altogether. The film’s attempt to steer the well-known craziness of actual political campaigns into the realm of the truly, courageously absurd isn’t altogether a failure. But in the end, The Campaign, like any professional politician, is first and foremost concerned with making the most people possible happy with it; it’s ready to say anything it needs to if that’s what it takes to attract audiences.