The concept of paradise looms large in the history of man. Whether in the purely ecumenical sense as in Milton’s Paradise Lost or Dante’s Paradiso, the secular world of Thoreau’s Walden, or the sociopolitical one of More’s Utopia, humanity’s longing for paradise has taken many forms, each containing an ineffable perfection that is as beautiful as it is unattainable. In the early 1930s, just as the country was to be swept up in Hitler’s rise to power, several German couples of various backgrounds sought their own earthly paradise in the remote and uninhabited Galapagos Islands. Graced by plants, trees, and animals found nowhere else on the planet, this was perhaps the perfect place to escape from madness that would sweet across Europe in the next decade. Yet it ultimately devolved into an ironic demonstration of man’s inability to escape man, and what briefly had the potential for a Waldenesque paradise quickly devolved into Sartre’s No Exit, where Hell is quite literally other people.

The whole story of Galapagos Affair: Satan Comes to Eden begins with Friedrich Ritter — a Nietzschean philosopher looking to test out his will to power — and Dore Strauch leaving Germany, and their previous partners, behind to create a life of their own away from all remnants of society. The press back home caught a sniff of their story, spread sensationalist headlines all over the papers, and drew the attention of another German couple, the Wittmers, who packed up and landed on the island a mere two months later. While Friedrich and Dore were resentful of the Wittmers for infringing on their privacy, holding them in relative contempt — even more so due to Margret Wittmer’s typically bourgeois personality — little did they know that someone far worse would soon descend upon them. And so, like straight out of some twisted amalgam of Swiss Family Robinson and an F. Scott Fitzgerald novel came Baroness Eloise von Wagner, with two lovers in tow, claiming the island for herself and making her desire to build a hotel well known to the previous inhabitants.

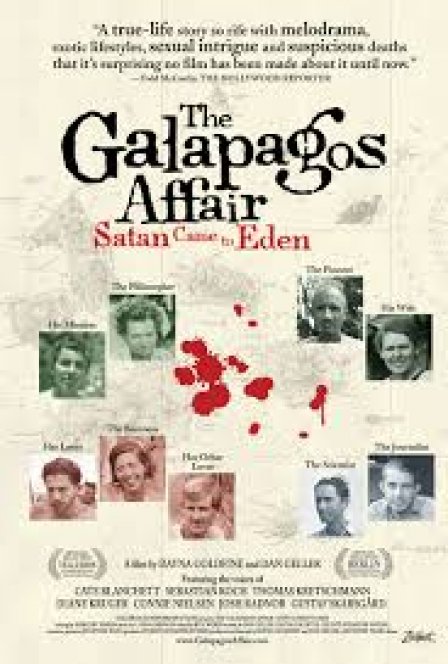

It is through the Baroness’s character — and I say character since her pomposity, villainy, and sheer brattiness would come off as too over-the-top and ridiculous even in a work of fiction (although the short film she shot on the island, which is shown in its entirety within this film, is quite remarkable in its sheer megalomania) — that the film presents its most fascinating events, as alignments are made, potential conspiracies develop, and people begin to mysteriously disappear. But while this lurid tale is inherently fascinating; and the wealth of video footage, pictures, diary entries and book excerpts (given life quite effectively by the voices of Cate Blanchett, Diane Kruger, and others) provide a respite from talking heads as well as a fascinating peak into existence in a unique and remote location; Galapagos Affair presents far too much filler with interviews of the original settlers’ descendants and the island’s newer occupants that offer little more than rumor and speculation that was already heavily inferred in the archival material.

Despite The Galapagos Affair’s bloated runtime, clocking in at a shade over two hours, the two-thirds of the film that is good is a very compelling illustration of the inescapability of human nature and the constraints of society. The archival material, particularly of the Baroness, makes it very watchable, but all the more disappointing in its refusal to delve beneath the surface and tackle the motivations of the film’s major players, from the two couples’ desire to flee Germany to the entanglement between the Baroness and the rest of the inhabitants. Rather than examining these issues in any great detail, The Galapagos Affair relies mostly on hearsay and conjecture, embracing the operatic nature of the island’s tragic mysteries instead of looking closely at all of the potential causes behind them and remaining blind to the broader philosophical implications of all the events it describes. Yet, as underwhelming as the filmmaking is at times, even a description of these events is enough to sustain a feature. The occurrences throughout the film are truly unique, not only in their bold melodrama and flare but in their fascinating representation of humankind’s insatiable, if entirely subconscious, desire to fuck everything up for everyone. There’s a reason fiction is packed with far more dystopias than utopias. We all know which one we’re really heading toward.