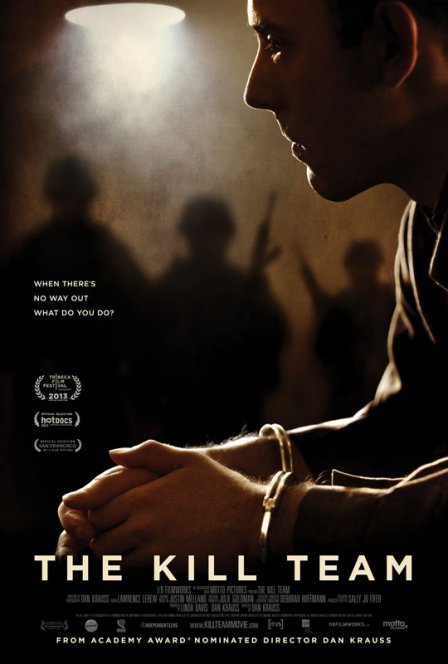

The Kill Team, the new documentary by Dan Krauss (The Death of Kevin Carter), is neither a great film nor a particularly strong piece of journalism. You should probably still see it, though: as food for thought, it says as much in its shortcomings as it does in its strengths.

The Kill Team is primarily the story of Adam Winfield, a US Army specialist deployed in Afghanistan in 2009. Somewhere in the middle of an interminable conflict that many recruits expected (and indeed wanted) to be an endless warrior battle, Winfield’s division comes under the charge of a sergeant who is willing to seek out the fights he craves, even if the “enemies” are unarmed civilians. To cover up the murder of innocents, this “Kill Team” plants weapons on their victims to make it look like the division was under attack.

Winfield doesn’t participate in these atrocities willingly, but he gets sucked in after his calls for help (via his father) go unheeded by army brass. The sergeant, catching wind of Winfield’s attempts at whistleblowing, threatens the young specialist’s life to ensure cooperation. When the story of the Kill Team is finally revealed by another soldier, Winfield is not rewarded for his abortive attempts to prevent his division’s misdeeds, but arrested for complicity. The fallout from this event makes up the bulk of the film’s narrative.

Before this mess, we see Winfield as a wide-eyed patriot, scrawny and well-meaning. He’s a typical suburban all-American boy, with an ex-Marine dad and a doting, protective mom; his determination to join the military despite his physical frailties is framed here as an underdog story. Although it may just be rose-tinted history, Winfield truly seems to be a good-hearted kid, with an almost pre-atomic notion of what it means to be a soldier.

Winfield’s innocence may be overplayed, but it’s far easier to sympathize with him and his rock-and-a-hard-place dilemma than with the other members of his division. These young men are an anti-war documentarian’s dream: arrogant, entitled children all, brainwashed bullies weaned on a steady diet of jingoism, binary us/them ideology, first-person shooters, and solipsism. Private Andrew Holmes describes his first time in combat as “intense… really cool,” saying that it immediately brought to mind Kenny Loggins’s hit from the Top Gun soundtrack, “Danger Zone.” Another private, Justin Stoner, has a cringe-worthy Twilight quote tattooed across his back and the pseudo-intelligent arrogance of every shitty “brogrammer” type you’ve ever met, and is perhaps the sickest fuck of them all: “You’re infantry. Your job is to kill everything that gets in your way. Then why the hell are [the army] pissed off when we do it?”

It’s hardly news that the modern US military is crowded with irresponsible, angry, emotionally detached young men for whom violence is just another game, but here The Kill Team’s narrow focus proves an asset. We are exposed at length to the psychology that drove these specific young men’s actions; the results are painful and infuriating to witness, but necessarily so.

This specificity also lends the film its biggest drawback, in that it downplays the typicality of its story. Stoner acknowledges at one point that “this goes on more than just us, we’re just the ones that got caught,” but it seems like the others involved have a vested interest in making their story seem anomalous. If one allows for this conceit, it makes it easy to erroneously frame the Kill Team’s barbarism as isolated, wrinkles in an otherwise smooth system. With this approach, the audience gets to keep its critical distance: one is invited to take a short walk in the shoes of the story’s victims and then move on, comforted by the fact that it is neither their problem nor that big of one.

In endeavoring to produce an objective portrait, Krauss also makes too many concessions to sympathy. While it’s admirable to not impose an authorial voice, kowtowing to the desires of the guilty parties allows them to maintain their ill-earned dignity on camera. One corporal only agreed to appear in the film if he could do so in his dress uniform, rather than the prison garb that reflects his current circumstances. You can smell the still-lingering sense of entitlement. That all of the soldiers involved in these monstrous actions are allowed this kind of sympathy, whether by intent or by oversight, reinforces the same issues that the film supposedly tries to illuminate. That they are even allowed to say their piece on camera also feels like a concession to the us/them mentality that created these little monsters in the first place, while the voices of their victims’ families are conspicuously absent. The “madness of war” notwithstanding, the Kill Team’s actions don’t deserve this sympathy. This is a far cry from Vietnam conscription; the havoc these men wreaked was their choice.

Speaking of Vietnam: the soldiers who made up the Kill Team are, debatably, the first military generation to come of age outside of that legendary disaster’s considerable shadow. In the wake of Vietnam, it was widely held that to be gung-ho about joining the armed forces was to invite being bent over the barrel by a heedless government. Much of that ideology seems to be wholly foreign to the current crop of soldiers. In a way, though, the shadow that follows them is even greater. All Americans, not just soldiers, suffer under the reign of a popular culture that trades in violence pornography and makes war seem “cool.” This has served to create, at least in the most impressionable youth, a drive to experience the very things that make war hell. Their military service is born not out of pride and goodwill, but out of bloodlust, an insatiable drive for nihilistic self-satisfaction. Soldiers enlisting now often want their own Top Gun or Black Hawk Down; to participate in a “legendary” battle would be the biggest kick, the ultimate goal of their service. They are signing up for the military not to build, but to destroy.

Maybe it’s naïve to think that all that much has changed. Either way, The Kill Team’s strengths lie in bringing these circumstances into starker contrast. If Krauss had had the guts to really rub his audience’s faces in it, then hold up a mirror to show the resultant filth, it might have garnered more than a cautious recommendation.