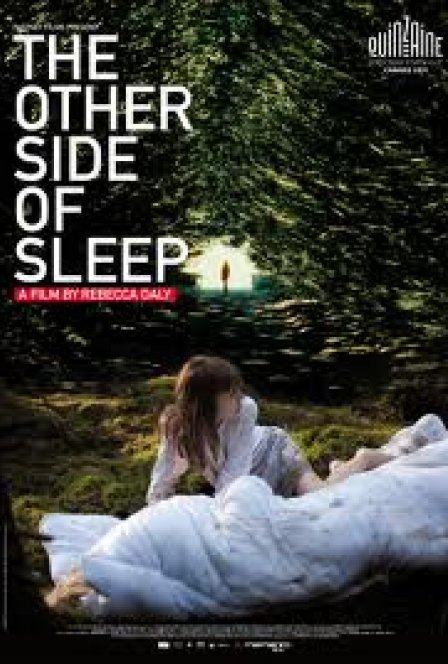

In an age where the independent motion picture is becoming increasingly marginalized, I find myself extremely reluctant to be critical of the minimalism (long takes, elliptical cuts and pensive slices of people doing things) employed by many of today’s directors. In a distraction-prone society, it’s understandable that such a trend persists. Subtracted, steely anti-meta narratives have their place in an increasingly overflowing zeitgeist that is virtually impossible to keep apace with. Patient films such as The Other Side of Sleep (the feature debut of Irish film-maker Rebecca Daly) are not easy to market, but not hard to appreciate if you let them speak to you.

Obviously, The Other Side of Sleep requires close attention. Not in the sense that it’s a puzzle, though it is billed as a mystery. It’s more that it needs to be raptly experienced in all its languorous detail in order for us to even begin to understand the protagonist. Effortlessly embodied by Antonia Campbell-Hughes, the taciturn, ephemeral Arlene is a tough nut to crack. Through the dichotomy of her connection to a recently murdered neighborhood girl vs. that of her coworkers, family and community, we are presented a character that is utterly unmoored. Nothing much makes sense to her except routine. She attempts to go about her sort of co-opting of the grief of a murdered girl’s family under false pretenses as though it were another day at the factory. But she’s not vacant. She’s older and younger than her years. There’s fear and compassion and cold light of day in those big doleful eyes. She’s ever changing, and no small-screen, multi-tasked viewing is going to make you appreciate just how vividly this is captured.

Empathy doesn’t come cheap. We’re selfish, instant-gratification fueled simps most of the time and can’t see or won’t see the point. There’s a practicality in this though, which almost frames Arelene’s seeming fascination/compassion with the horrible loss of a neighbor as dysfunction. She doesn’t come at the situation in an empathetic fashion because she had literally sleepwalked to this girl’s body. It’s as though she’s been lost a long time and now believes her subconscious mind is telling her something. Perhaps she’s sensing more of a place for herself in the world. But the community is cold and unsupportive toward anything out of the ordinary and she seems doggedly convinced that her part in it is merely utilitarian. It’s a singular oddball story in that the protagonist only reclaims their meager status after a life altering event. Ultimately, it’s being able to work and not think so much that reprieves her from encroaching madness.

Despite its initially grim whodunnit atmosphere, this is no genre picture. It is a sharply rendered, miniature portrait turned around so much in the hands as to have frayed, uncertain edges. It is perhaps best appreciated as a study of loneliness, and why we often cling to it. It beautifully shows how an alienated person may experience the death of someone who’s more connected to the world than themselves as a sort of communion. Arlene tries to experience physical intimacy, but is only shocked by the raw frailness of it into remote silence. She is a tragic figure in a world where we depend on symbiosis and physical contact much more than we realize. It wouldn’t matter if this story was set in a city, as aloneness begets aloneness wherever it finds us. But the cyclical, finite nature of the small midland village where Arlene mildly metes out her days illustrates this exponential solitude perfectly.

So while I may’ve had my aesthetic gripes (the agonizingly played-out ablution shower sequence is here, as are distractingly flashy insert shots to underscore intensity) and a bit of weariness over the seeming continuation of the “I can show less than you” contest among directors, I can only recommend this film. The above observations are mostly intuited from my own notions of the human condition, as The Other Side of Sleep is a decidedly elusive story. It may confuse. It may aggravate. But its spooky realism (no musical score), fine performances and gorgeous cinematography by Suzie Lavelle will be enough to entice and reward the adventurous viewer.