In Drib, one of the selections at this year’s SXSW, the film’s subject invokes critic Manny Farber’s comparison between “termite art” and “white elephant art” — more or less the difference between art made in the margins and that created with the blessings of prestige. It is useful to reflect on this difference in light of the festival itself, which has, over the past decade, transformed from music fest sidebar, to bastion of zero-budget filmmaking, and finally to red carpet premiere destination for studio and higher-budget indies. As SXSW has evolved into more of a marquee American film festival, it has sometimes struggled to balance its new life as a celeb destination with its name-making reputation for finding, and sustaining, new voices with unusual ideas. It is maybe telling that some of the filmmakers first nourished by the festival have returned this year with their most accessible films to date — and yet, the festival’s programmers have remained committed to finding space (sometimes, indeed, on their program’s margins) for emerging filmmakers trying to find something else.

This dialogue between the mainstream and the underground gives SXSW a lot of its particular flavor, and part of the excitement of being here is the potential to stumble into films you didn’t even know you were looking for. What follows is an imperfect hunt through the festival’s underbrush. Some movies that are very much worth your consideration — particularly Janicza Bravo’s Lemon, Erik Ljung’s The Blood Is At the Doorstep, Mónica Álvarez Franco’s The Cloud Forest, and Yuri Ancarani’s The Challenge — are overlooked, which is regrettable, but you should find those movies and watch them.

Rat Film (dir. Theo Anthony)

The only film at this year’s SXSW I was hard-pressed to find anyone with a bad thing to say about it, Rat Film charts the history of vermin control in Baltimore to weave a dense parable about the city’s legacy of racial segregation. Anthony pulls from many sources (interview, portraiture, primitive 3D imagery, android narration, historical record) to bring hard, damning evidence about who is valued — and who gets thrown away — in America. Anthony shows his skill as a filmmaker by saying much of this through his imagery, which is frequently unforgettable, and does the heavy lifting of tying complex ideas together naturally. If the film has any weakness, it’s that the visionary rat-controlled sound generator by Baltimorean Dan Deacon (who also contributes the score here) gets frustratingly little screen time. A great film that speaks intelligently to the long, horrific road that led to this period in American history, and whose closing image will haunt you for the rest of your days.

Lucky (dir. John Carroll Lynch)

A kind of special effects-driven movie where the “effect” is age, Lucky (the first feature from beloved character actor John Carroll Lynch) is defined by its lead performance from Harry Dean Stanton. Ninety years old and still going, Stanton seems to be the film’s reason for being, and the legendary actor gives the picture more than just a presence: co-written by Stanton’s longtime assistant Logan Sparks, the script borrows much from the man’s biography to tell the low key story of a long-retired crank shuffling through a lifetime’s worth of regret in a marginal desert town. It is quirky in the way we now expect ‘indie’ films to be, and full of the sort of big moments often found in films directed by actors, but Lucky has heart, is stacked with memorable cameos (Tom Skerritt’s one scene soliloquy is a highlight), and stays enlivened by Stanton’s easygoing, “I’m here for the cigarettes” performance. Plus, you get to watch Stanton and longtime friend/collaborator David Lynch (no relation to John Carroll) bounce lines off each other for what feels like half the movie (Lynch looks pretty good in a hat, in case you were wondering).

Easy Living (dir. Adam Keleman)

As driven by its lead as Lucky but in every other way made on a different planet, Easy Living is the sort of movie one hopes to find at film festivals but rarely does: independent, personal, and bonkers. Director Adam Keleman’s vision of an alcoholic makeup saleswoman (an incredible Caroline Dhavernas) starts off with a familiar dynamic: will our hero clean up her act, or stay a trainwreck forever? At times edging into Lifetime movie territory, Keleman gradually ups the crazy while matched step for step by Dhavernas’s willingness to “go there.” By the time the film hits its out of nowhere third act, you just kind of have to go along for the trip, unforgettable dialysis machine sequence and all. Like a pizza with every topping, Easy Living gives you more than you ever asked for: melodrama, high camp, robberies, townies, a primer on small business loans, and an ultimately sincere look at the difficulties of living life on your own terms. In a film culture that withholds so much, it is refreshing, for once, to be granted plenty.

Satan Said Dance (dir. Kasia Roslaniec)

The third feature from Polish auteur Kasia Roslaniec has a curious double life: though screened here in a feature-length cut for festival purposes, Satan Said Dance was conceived as a nonlinear, interactive piece in which viewers use an app to assemble its scenes into a sequence of their choice. Though the official synopsis describes it as an “Instagram film,” this is simply a film through and through. Telling the transfiguration story of a fledgling novelist who crashes, burns, and comes back to life (not necessarily in that order) through the crucible of the European hipster party world, Satan embraces the fragmented feeling of online videos to more deeply capture its protagonist’s view of the world. The avalanche of party scenes can feel repetitive, and in this viewer’s opinion not all of the sequences work — but in taking the risk to find a new language native to this era instead of just cynically throwing together an app-based social media campaign, Roslaniec deserves a lot of credit for succeeding at the high level she does. That the filmmaker asks you to decide for yourself what works and what doesn’t provides a freedom few directors allow or encourage, a trait which, in its best moments, makes Satan Said Dance seem nearly heroic. Here’s hoping that other filmmakers act on the challenge Roslaniec has thrown down.

Sylvio (dir. Albert Birney)

Another, very different film drawn from the landscape of the internet, Sylvio began life as “Simply Sylvio,” a long-running series of Vine videos starring the eponymous anthropomorphic gorilla. The Vines were charming and, well, simple, qualities that largely carry over into the creature’s feature length debut. Co-directed by “Sylvio” creator Albert Birney and SXSW legend Kentucker Audley (the man who put “Movies” on a hat), the film grafts an underdog-battles-the-odds plot (and a backstory) onto its silent star, throwing the hapless ape into a quest to save a local public access talk show while staying true to his autobiographical puppet show (long story). Slight and stunningly low-stakes, Sylvio is at its best when it relies on what the Vines did well: deadpan physical comedy and Sylvio’s natural charm. Those with a weakness for meticulous production design and tender fantasy will most likely fall for the yearnings of this young, sensitive primate trying to find his place in a mixed-up crazy world.

Person To Person (dir. Dustin Guy Defa)

Can kindness be a radical act? Person To Person seems to suggest as much, and your appreciation for it will probably depend on your ability to accept a film on terms this gentle. Set over one ambling, reasonably paced day in New York City (and one with really nice weather to boot), Dustin Guy Defa’s follow up to SXSW alum Bad Fever is as open-hearted and pleasant as his debut was one long angst nightmare. Defa has made a series of accomplished shorts between these two features (including the excellent introduction to this film’s “Bene” character from 2014, also titled Person To Person), and one can’t help but see this latest work as the culmination of his half-decade of experimenting with character. Though the film features some recognizable faces (Michael Cera and Abbi Jacobson maybe most of all), Defa privileges nobody and depends on his full ensemble, building a series of stories that don’t so much interlock as run parallel to create a unified, lightly connected image of city life. Person is probably nails on a chalkboard to somebody not receptive to its particular, breezy vibe; this viewer, however, fell hard for its tribute to friendship and the modest doses of happiness that make life worth shuffling through. Generous throughout, Person To Person returns the affection it invites from you right up to its final, heart-stopping declaration of love.

Maineland (dir. Miao Wang)

Miao Wang’s previous, excellent feature Beijing Taxi used the stories of local Beijing taxi drivers as a gateway for the director to understand the ways in which her native city had changed in the years since she had moved to the U.S. In Maineland, Wang flips her strategy, following a group of upper-class Chinese teenagers as they leave home for a boarding school in Maine. Perhaps reflecting her own young expatriate journey to the states, Wang’s film dives into the emotions of these kids in an unfamiliar place, showing both the difficulty they have relating to their new home as well as the occasional comforts (scenes of the students meeting up at the local nondescript Chinese takeout place are both touching and a little sad). As they debate what to make of their futures, their personalities, and capitalism, Maineland reveals itself to be not only a portrait of these children of the elite — and probable future leaders of the free world — but of the complexities of adolescence itself.

Win By Fall (dir. Anna Koch)

In its own way a fitting companion piece to Maineland, Anna Koch’s Win By Fall (not to be confused with the similarly titled Joe Swanberg movie that came and went here) also uses the documentary form to chart the growing pains of a group of boarding-school students. In her case, however, Koch stays at home and digs deep into her native Germany to chart the trials of a quartet of girls at Frankfurt/Oder’s “Elite School of Sport,” a highly competitive wrestling program. Using the familiar structure of a sports film (we even have our countdown to the Big Game), Win By Fall elegantly compares the agony of failure, and the thrill of victory, to inherent anxieties about the body, status, and identity by blowing it up to a competitive level. Gorgeously shot, and edited with a crispness that always gives you just as much as you need at any moment, Win By Fall nevertheless seemed strangely overlooked at this festival. Perhaps the world of German teenage wrestling is too niche for a general audience, but for those willing to seek it out, Koch has given you a great, memorable film about the big questions of youth.

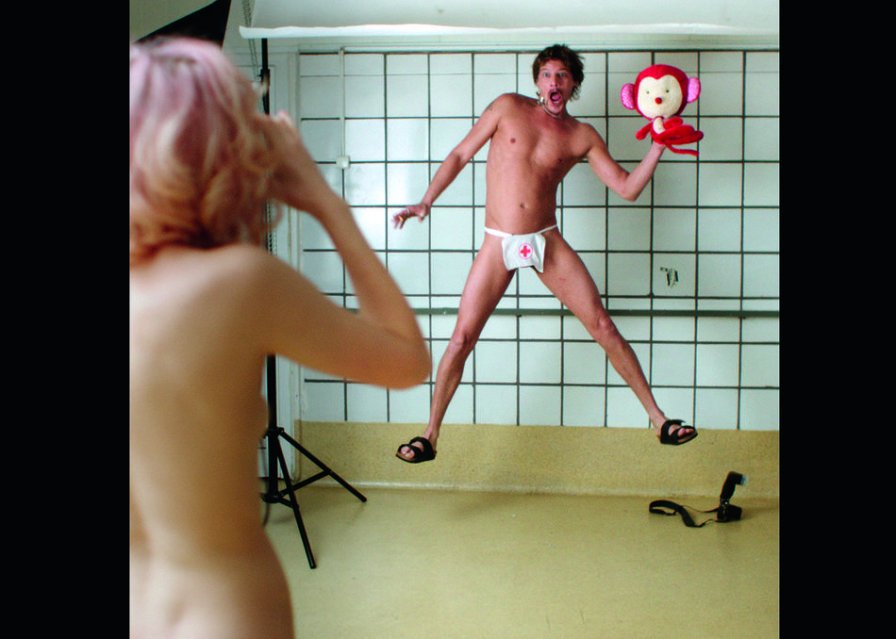

Drib (dir. Kristoffer Borgli)

If Kiarostami’s Close-Up was about branded content, and also totally jacked-up, you might get something like Drib, a metafictional account of one prank artist’s attempt to troll the system — and how it undoes him. Andy Kaufman-worshipping Norwegian comedian/viral video star Amir Asgharnejad recounts his attempt to get a famous energy drink company to hire him as their spokesman, and things predictably go from bad to worse. Complicating the tale, however, is the presence of his friend Kristoffer Borgli (the director of Drib), who stages reenactments of Asgharnejad’s story starring… Asgharnejad himself. As these mirrors fold in on themselves, Borgli asks us to puzzle out the truth not only of Amir’s story but his own reenactments of them, raising the question of whether it is ever possible for someone to tell a story honestly through mediation. A bitter bloodletting session about this present era of Vice-approved “edginess” (embodied in the film by Amir’s antagonist, a perfectly cast Brett Gelman as an insufferable, Faustian ad exec desperate to stay relevant), this film speaks so immediately to its moment it feels as if it’s being made while you’re seeing it. Animated by an extremely on-brand score from PC Music associate Felicita, and stuffed with the same hi-gloss, ad-world imagery it parodies, Drib is dizzying, compulsively watchable, and a real blast. Don’t forget to like and subscribe for additional content.

I’d also like to give an honorable mention to Kristen Lepore’s short film Hi Stranger, which screened in the Midnight Shorts block and sat on my mind like a curse ever since. Perhaps describable as “dark ASMR,” Lepore’s brief, deeply unsettling animation is best seen with no preparation —other than to say that if you have problems with intimacy, well, hold on tight. Hi Stranger can currently be viewed for free on Vimeo.