We’ve heard it trumpeted countless times from the self-appointed tastemakers, the hidden hand offering up distressed jeans and cell phone minutes: young men want to be rock ‘n’ roll stars. One by one, they march to the killing floor, bright-eyed and naïve, flailing about for the elusive gold star, eking out a living on meager wages and flagging hope, or else never really getting started at all, resting the Squier on the barely-used practice amp and moving on to a future in public administration. “Yeah, I tried the rock thing,” the craggy silver fox will intone in voice-over, dismounting his Harley minutes away from an out-of-frame slamming-down of two HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. “Didn’t quite pan out. But I know the dream is still out there.”

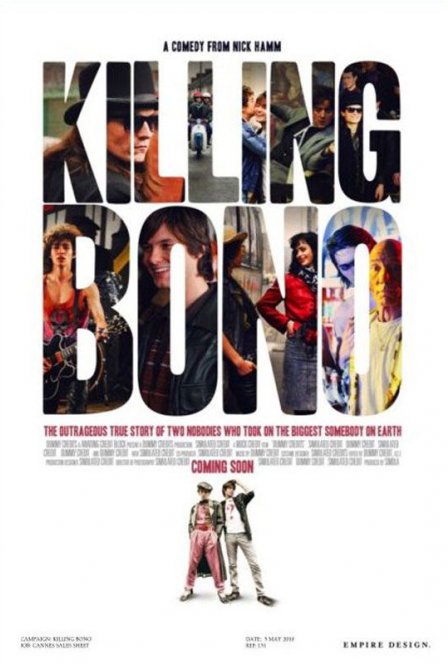

Dublin native Neil McCormick (Ben Barnes) is all too happy to be acting out his own particular version of this modern myth in Killing Bono. He has internalized the idea of himself as an aspiring rocker; it has become as much a part of him as his brown hair or his off-putting demeanor. There is little in the way of explication as to how he became this way beyond the usual articles of faith: fame, sex, wealth, and glory. It is good to be a famous musician, and so Neil would like to be one.

Great suffering lies in store for Neil. He recruits his hapless brother Ivan (Robert Sheehan), and they set off for London. Perpetually poised on the brink of success, some absurd sequence of events (often set into motion by Neil himself) invariably sends the brothers plummeting back into the depths of despair and obscurity. Still, they toil on, hunkering down in a dank studio space, living off of money loaned to them (in one of the film’s more bizarre plot elements) by the Irish mob, setting up poorly-attended gigs, and shopping their songs to fly-by-night record execs. The two make quite a pair, with Neil’s rampant egotism and lack of foresight doing what it can to counteract Ivan’s doe-eyed naïveté and tendency to crack up in the face of adversity.

Neil is continually spurred on by the unimaginable success of four of his school chums who form a band and turn out to be U2. Mocked relentlessly by their rapid ascent into a global phenomenon, Neil’s resentment is compounded by his guilty conscience at having prevented Ivan from joining the band at its inception. Neil and Ivan watch U2 perform at Live Aid, as Bono hoists the weight of the world onto his shoulders, dances with fans in the mud, becomes Jesus, and goes back on the road to smoke cigars with Sinatra. The misery continues.

This tableau becomes tiresome, then oppressive, a fate the film could have avoided by making the two main characters sympathetic or at least engaging. Ivan is a nonentity until he shows up to whine about something. Neil is never fully fleshed-out as a misunderstood hero or a scrappy up-and-comer or an idiot or whatever he is, and so ends up wavering between broad caricature and psychopath. His naked desire for stardom fails to charm or to even be interesting as a variation on the canonical rock ‘n’ roll narrative.

Attempting rock idolatry is of course a ridiculous pursuit, and not only because there is such a minuscule chance of success. In order to succeed at the level Neil is striving for, there is much pouting, press-baiting, and shape-throwing that must be performed. This is fine, as long as you commit. Barnes, though, ultimately play-acts the play-acting, his rock star poses so self-consciously silly that they throw his character’s intentions into question. To be a Mick Jagger or an Ian Curtis or even a Bono, there must be at least some sense of danger or gravitas behind the spectacle, if the performance is not to become laughable.

Neither does Neil benefit by comparison to the other, more convincing rock stars of Killing Bono. Mob boss Danny Machin (Stanley Townsend) resembles a bass player for an early heavy metal band after too many nights of booze, coke, and backstage deli spreads, leaving him with a lumbering, decadent calm that slides into villainous rage. Similarly resembling a rocker gone to seed is Neil and Ivan’s landlord Karl (the dear, departed Pete Postlethwaite), though he hews more toward the glam end of the spectrum. Outdoing them both is Hammond (Peter Serafinowicz), music industry hustler extraordinaire, a nihilistic Tony Wilson cum rage-filled Lionel Hutz.

Serafinowicz wallows in Hammond’s sleaze-encrusted aura, his heavy-lidded eyes projecting the exhaustion that comes with having to coddle an endless procession of man-children. His single-minded pursuit of profit and notoriety stands in contrast to Neil’s in that Hammond does not harbor any delusions of grandeur. “I don’t even like music,” Hammond admits just past the film’s mid-point, and it comes as a breath of fresh air.