There’s little new in the argument that it’s exploitative to forge art out of the misery and annihilation of others. We all know the story: a composer, director, or writer coolly appropriates the notoriety and emotional resonance attaching to a particular tragedy or inhumanity, siphons it into her latest work, and simply reclines in her chaise longue in anticipation of the plaudits, while the subjects of her profound “study” either continue to suffer or continue to rot. This shtick is made all the worse by the fact that we — the audiences of such questionable band-wagoning — often use the offending artifacts to perpetuate the self-satisfied lie that we’re compassionate, conscientious, and committed people, when in fact many of us probably spend the time outside of our agony tourism never uttering a word to our neighbors, never offering rides to hitchhikers, and never giving to charity. And yet, if a war film or holocaust novel can change a single person’s attitude and outlook to the extent that this change improves their lives and the lives of those around them, then surely this offers some appeasement for the guilt that can infest those who are venerated simply for sticking a camera in front of a starving child.

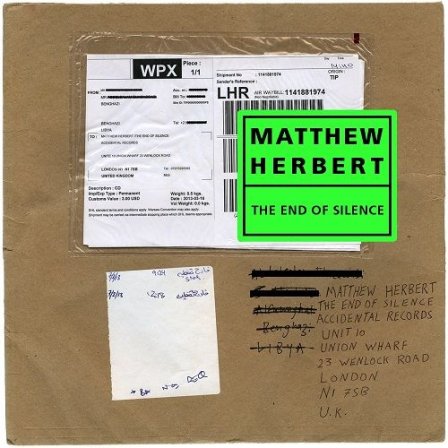

It’s because of this potentiality for renovating worldviews that we should ply cautious optimism to Matthew Herbert’s latest album, The End of Silence, which among his already semi-polemical albums has the potential to be his most divisive yet. Sculpted (almost) entirely from a 10-second soundbite of a bomb that, in March 2011, was gifted from pro-Gaddafi Libyan warplanes into the vicinity of photojournalist Sebastian Meyer, it represents what Herbert himself has elsewhere described as an attempt “to freeze history, press pause, [and] wander around inside the sound” of engineered destruction. And while the (simulated) exploration of the innards of this destruction may not make for the most hospitable or easygoing electronic album of the year, it undoubtedly goes some way to achieving its stated aim, even if its ethics could conceivably be indicted from the above-mentioned angle.

Though, it should be relayed at this juncture that Sebastian Meyer was not wounded in the air attack that he recorded in Ra’s Lanuf (although it’s not clear whether others were similarly fortunate). Nonetheless, the opening of the album feels like the confused and shell-shocked aftermath to a cataclysmic event. Inaugurated by the unedited and inexhaustibly jarring audio of the airstrike, “Part One” immediately collapses into a stuttering, introverted and emaciated loop of miniscule glitches. These are intermittently joined by a series of yawning bursts and whirs, fragmented atmospherics that together with the narrow oscillations of the piece’s underlying heartbeat induce a massive sense of isolation, detachment, and disorientation. Even though Herbert has explicitly declared that his intentions were to dissect the texture and composition of the blast itself, it’s easy to arrive at the parallel notion here that The End of Silence is just as much a portrayal of the devastation that followed in its wake. Listening to the first 10 minutes of “Part One,” with its woozy pulses and its wafting of charred static, a picture quickly emerges of a violence that has stripped its victims of their humanity, reason, and emotion, and reduced them to little more than shambling, anthropomorphic husks. Reading into its stuttering, unnerved destitution even further, it’s possible to claim that Herbert is trying to tell us that violence and humanity are mutually exclusive, and that the one renders the other completely impotent and irrelevant.

Even when he pulls us out of this initial meltdown and solidifies a more accelerated and borderline harmonic rhythm, we still find that the gradual reconstruction of normality, or civilization, is permeated by the brutality that founded it. Throughout the album’s duration, the original clip of the detonating bomb makes sporadic reappearances, as if the object of post-traumatic flashbacks, and when it reasserts itself around the 16-minute mark of “Part One,” a repeating, industrialized siren marks the point at which the album becomes more animated and sonically dense, although not without escaping the effects of its original wounds. “Part Two” continues this slowly resuscitating trajectory, yet at all times, the increasingly agitated, discombobulated energy it manifests is disturbed and disrupted by arrhythmic bleeps and snatches of feedback, as well as the occasional caesura of digital noise. It’s almost as though the memory and threat of violence is still far too omnipresent for the music to regather anything other than a tokenistic semblance of human coherence, and there’s something faintly absurd and unsettling about the track’s dubby, nearly danceable motif when heard in the context of the tumultuous chaos that bookends it.

Needless to say, “Part Two” is killed off via a spasmodic reiteration of its lightheaded “hook” and a wash of radio hiss, charting perhaps the undignified and almost inevitable demise of any attempt to be civil or humane in a war zone. Yet if it evokes the hopeless absurdity of modernistic culture in a fundamentally violent world, then “Part Three” would convey the inured numbness or stoicism that might be the only sanitary adaptation to the strife of the battlefield. Beginning with quickfire volleys of ordnance fuzz and the quasi-ghoulish whines of some computerized whistle, it eventually lurches and hobbles its way to a bassy, halting riff, which in its subdued yet poised cycling could be regarded as the point at which the bomb’s casualties finally obtain some much needed repose, even as the replaying of the bomb’s descent continues to recur at sporadic intervals. And there’s a certain power imparted by the fact that this phlegmatic, abstracted figure is completely undeterred by and oblivious to the explosion’s continuing reproduction, suggesting that it has resigned itself to the permanence and irresistibility of violence/war as the basic substrate of human existence.

Yet regardless of this figurative and conceptual clarity, and regardless of how vividly as a wholeThe End of Silence represents the manner in which violence stunts and confounds any endeavor to transcend its ultimate authority, two questions still remain unanswered. The first relates simply to whether this all amounts to an unwaveringly “enjoyable” or “stimulating” listening experience, and the answer to this would be a qualified yes, that is, qualified to acknowledge the moments of uncomfortable stasis and inertia into which Herbert occasionally submerges us. The second question — Is the album’s commodification of bloodshed justified or redeemed by its edification of the listener’s politics? — is less straightforward, however, and the album’s symbolism might even suggest that all improvements in ideology are instantly rendered vapid and obsolete by any immovable show of violence. But having said that, I hope that someone less pessimistic and self-absorbed than myself will listen to the gravity of The End of Silence and will take it as a cue to stop being silent themselves.

More about: Matthew Herbert