We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music and films that helped define the year. More from this series

2013: The Year Offense Criticism Ruined Art and the Internet

In 2013, real-world news seemed to arrive as fully formed myths — larger-than-life events that both encapsulated and magnified the tensions that characterize our more mundane, everyday lives. Race? George Zimmerman, Trayvon Martin. Economic uncertainty? Detroit. Sexual orientation? Proposition 8/Defense of Marriage Supreme Court cases. Gender? Chelsea Manning. Safety? Boston, Sandy Hook. Consumerism and globalization? Bangladesh. Privacy? Edward Snowden.

But while it’s hard to think of another year in which so many decades-long debates could be distilled into mere proper nouns, despite how iconic these stories were, none seemed to adequately capture our collective 2013 preoccupations. Or mine, at least.

Sure, I was shocked and disturbed by the Sandy Hook shooting, and I held my breath for the Zimmerman verdict. But I didn’t spend days afterwards lost in endless chains of articles debating their implications for American society and lighting up our social media.

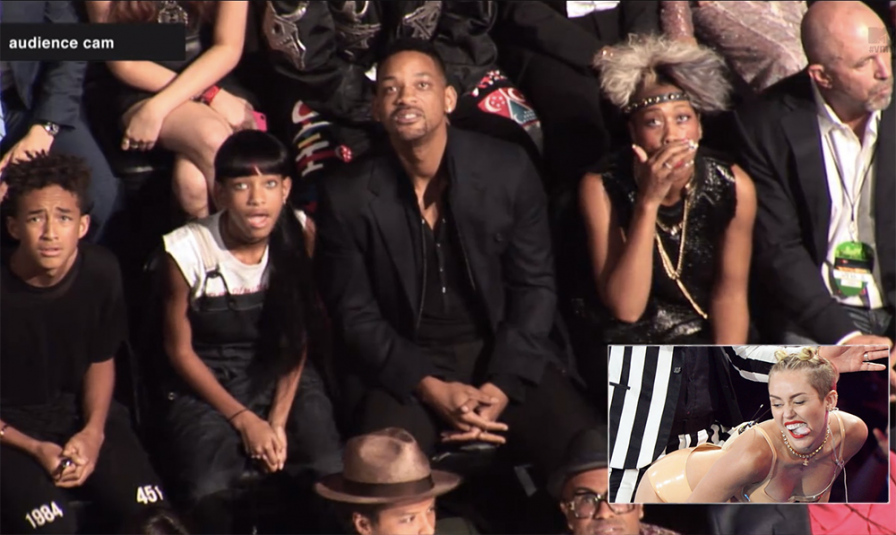

That was reserved for more urgent questions: Is that one Robin Thicke song rapey? Should white girls like Miley Cyrus be allowed to twerk? Should Lily Allen be allowed to make a video commenting on said white girls who twerk? What is thin privilege, and how can we reconcile it with the fact that most obesity worldwide is in rich countries? Speaking of thin privilege, does Lena Dunham hate black people because there aren’t any in her show? Also, do the lyrics to the new Kanye West album mean that he hates women? And just how, exactly, is Kanye West’s fist like a civil rights sign, and wouldn’t that give some awful splinters?

Instead of worrying about the state of the real world, I spent this year obsessed with online debates about the media’s representations of it.

Instead of worrying about the state of the real world, I spent this year obsessed with online debates about the media’s representations of it.

And judging from Google search results, I wasn’t alone. Type in “Miley Cyrus twerk*” and you’ll get 372,000,000 results; “Trayvon Martin” yields a paltry 109,000,000. “Blurred Lines rape” is at 103,000,000, which is still four times “Supreme Court Defense of Marriage,” with 12,100,000 pages. Global events follow the same pattern. “Lorde Royal?” 70,500,000 — more than the number of people who live in the Kiwi singer’s home country. “Bangladesh factory collapse?” 2,940,000.

But were we really more concerned with whether there’s too much boob in Game of Thrones or too much white people in Girls (“Girls show racist”: 35,700,000) than we were about whether there are too many actual black people in prison? (“African American prison population”: 2,480,000; “Orange Is the New Black”: 74,400,000) Or is this imbalance of attention more a product of displacement than disinterest?

After all, our interest in media seemed to revolve more around finding offense than it did finding refuge (thankfully, since “having fun” and “escapism” are #privileged, #thingswhitepeoplelike, #firstworldproblems). Gracias a sites like Flavorwire, Buzzfeed, Jezebel, The Atlantic, Salon, and Upworthy (and our devoted patronage of them), the bulk of our discussion about songs, music videos, TV shows, and films — many of which most of us otherwise wouldn’t have even seen — was limited to their ability to be offensive in terms of race, gender, and sexuality1.

Of course, maybe our internet-assisted cycle of consumption and subsequent regurgitation ))<>(( of pop media was actually a form of self-conscious hand-wringing that belied a deep concern for some of the same political and social discourses we refused to engage with IRL. But even if we were just projecting our societal anxieties about the real onto the imaginary, it was the imaginary that suffered most of the negative impact.

TL;DR: Miley Cyrus’s twerking probably didn’t hurt race relations in the US, but the endless “offense criticism” it inspired did hurt our relationship with art.

Being Offended by Art in the Age of Digital Reproduction

Being offended by art isn’t exactly new. A century ago this year, Igor Stravinsky’s ballet The Rite of Spring nearly caused its audience to riot during its premiere at Paris’s Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. Presumably, wealthier patrons expecting an easily-digested traditional ballet got their monocles in a knot upon seeing the avant-garde performance’s then-groundbreaking violent, erratic choreography and similarly rule-breaking — at least for the venue — music.

A hundred years later, showcasing unfamiliar dance moves (twerking) in a new setting (the mainstream) can still apparently cause an uproar. And at their most basic, our justifications for being offended — whether overly rigid moral codes, misguided objective ideas about good taste, or impermeable boundaries between collective identities — haven’t changed much, either. Nor has the language we’ve used to say, “Harumph!” Stravinsky’s critics called The Rite of Spring “puerile;” this year, after her VMA performance and We Can’t Stop video, internet criticism zoomed in on Cyrus’s relationship to her own childhood.

But there is an important difference between offense at art today and nearly all of its previous incarnations: unlike the audience in the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées — who heard about the ballet beforehand, made the journey to the theater, paid for tickets, and waited in line with anticipation — most of us actually have no investment at all in the art that pisses us off.

Igor Stravinsky at the 1913 VMAs

Igor Stravinsky at the 1913 VMAs

Miley Cyrus being highly offensive

And neither do critics. Stravinsky’s naysayers were ballet and classical music aficionados, near-comedically well-versed in and obsessed with the minutiae of the form’s history and technical elements. But I’d hazard a guess that most of Cyrus’s internet critics didn’t even know what key her song was in, or otherwise care about her music2.

This shift in audiences’ and critics’ relationship to the art they hate is tied to historical changes in both media production and distribution, as well as in our relationships to them. Around the 1970s, university English and art departments, which formerly upheld the traditional artistic tastes of the upper class, were infiltrated by the cultural studies valuation of working-class artforms like TV and blockbuster films. Soon afterward, identity-centric ideological critiques like critical race theory, post-colonialism, queer theory, and feminism came to dominate academia’s approach to visual art and literature. At the same time, TV and radio channel proliferation began to chip away at what was formerly a single, national mass media market — and with it the notion that any particular program should appeal to the values and tastes of a national or global audience. Today, technologies like torrents and streaming content continue to fracture audiences even further, with the added complication that content became, in many cases, free.

1. Perhaps not accidentally, class — and along with it, issues of economic justice and equality — was pretty much ignored besides vague allusions in the ever-present privilege discourse.

2. Without curiosity about, or investment in, what makes art tick, what’s left to say besides surface-level critiques about how art illustrates, or even causes, our most ubiquitous social ills?

We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music and films that helped define the year. More from this series