We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music that helped define the year. More from this series

Obama’s dirty secret is how he spends his time alone. Each night after dinner with his family, he removes himself from all company, and late into the night — with seven lightly salted almonds — he focuses in the personal quiet of the White House’s Treaty Room. There he reads letters that have been addressed to him, works on the next day’s speeches, catches up on current news, and perhaps allows the light background presence of a game (if one of his teams is on). When The New York Times reported this long-running practice of Obama’s, it was already quite late in the president’s career, and it came out as a mild, little-known narrative factoid — nothing too noble and nothing too astounding.

How did our past presidents become publicly intimate? FDR held his “fireside chats” — prototypical stagings of familial intimacy at the dawn of live mass communication. John F. Kennedy forced the public to engage with the corporeality of public figures through his own death: a horrific reduction of the world’s foremost figurehead — the president, an emblem of power and values — to a precarious organism, shattered and splayed against car seat leather and the first lady’s dress. Then, in another event of blowing up, Bill Clinton’s intimate life erupts with the graceless event of a sex scandal. Here lies the context for the cheeky New York Times headline that frames the outing of Obama’s late hours of solidarity: “Obama After Dark: The Precious Hours Alone.”

Obama’s contribution to the lineage of performances of public intimacy by US presidents is stunning, because it is subtle and silent in this case. Barely noticeable, those several hours that the president spent alone every night for the past eight years were self-gratifying and unannounced, bearing the integrity of their commitment to the real as opposed to the spectacular. In his separation, however mediated it may be, Obama finds a moment of personal repose.

Chance Meeting

There is so much that can be (and has been) said pointing toward the ways in which the presence of the spectacle — as postulated by french philosopher Guy Debord in 1967’s The Society of the Spectacle — has only become more apparent and imposing in the five decades since its postulation. It has become painfully clear that Debord was correct when he wrote that while the early economic domination of social life “entailed an obvious downgrading of being into having that left its stamp on all human endeavor,” we currently exist in the stage of domination that “entails a generalized shift from having to appearing” (emphasis mine). Debord continues: “all effective ‘having’ must now derive both its immediate prestige and its ultimate raison d’etre from appearances.”

The spectacle, in short and in so far as I will use the concept, represents the alienation suffered through the fragmentation, totalization, and representation of social experiences as they are mediated by economic technologies, including the spectacle’s “most stultifying superficial manifestation,” the mass media, a technology now partially understood as the online media through which we receive new terms of self-presentation and connectivity. As significance is more greatly represented and understood through follows, likes, and shares — regardless of whether or not the originating event of those engagements (the performance of a song, the end of a relationship, the brutality of police, etc.) was at all concerned with online significance — it becomes clear that the veracity of being has shifted in some degree to appearing. In that shift, being is hyper-stimulated, ever present and presentable.

Ben Ratliff writes on music in this age of hyper-representation and alienated non-meaning in his recent book Every Song Ever. He lends an approach toward coping with (and perhaps appreciating) saturated cultural abundance. Each chapter outlines a different quality found in music across vastly different sources (these are broad qualities: slowness, fastness, loudness, silence, repetition, etc.), suggesting that if one can find what is to be appreciated about any piece of music they come across, they are more well-prepared to traverse the contemporary music listener’s landscape of hyper-availability and algorithmic introduction. Ratliff’s enticing sense of openness when listening is valuable insomuch as it lends itself well to acceptance, appreciation, and tolerance. However, in its endgame, it turns the listener into a fine-tuned processor of the cultural noise of music genome models like Pandora and Spotify Radio, a post-Fordist interpreter of the endless data-curated mix.

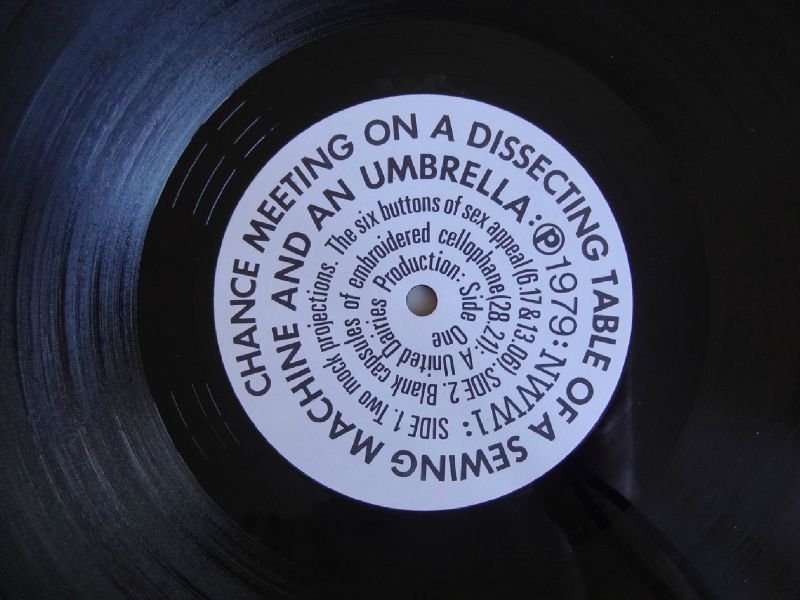

Two somewhat recent articles come to mind for illustrating the pitfalls of becoming Ratliff’s ideal listener: (1) this article about DJ Screw by clipping.’s William Hutson, which begins by expressing frustration at the elevation of DJ Screw’s music without an appreciation of the southern rap that begot it; and (2) this L.A. Weekly article outlining the cultural thrust of a particular list of “weird” music artists donned on the artwork of the Nurse With Wound album Chance Meeting on a Dissecting Table of a Sewing Machine and an Umbrella, a “Rosetta Stone, in the form of a cryptic list of names looking for the right person to decode it.” Each of these takes on music appreciation values the listener’s cultural experience and point of reference over their analytical (or even emotional) comprehension of a piece of music. While Ratliff’s listener simply copes with the anxiety of listening within our current manifestation of the spectacle, the above stories remind us that music mediates — and is mediated by — culture. The positions of the geek (the fanboy) and the specialist (the collector) are the ones who better grasp the social meaning of musical life, standing with their feet in the soil of being and having, respectively.

Scrolling (Fall Forever)

Last month, I deactivated for the first time, although I’d always known my day would come. My Facebook habit filled the tiny cracks in my day until I came to self-diagnose bouts of scrolling as signs of unresolved anxiety. If a moment could be deemed too short to actually work on a task, it was the perfect amount of time to scroll for a mild fix. Days went missing in the form of lethargic, slow-burning panic attacks.

Somehow, I found comfort this year when I got around to reading Tao Lin’s Taipei. The novel is heavy with drug use such that it renders itself as an ever-collapsing tranquilized daze. Taipei’s protagonist Paul makes an island of himself when he loses a sense of relation to others beyond the drugged experiences shared with them. Throughout the novel, this drug/relation theme is forcibly entangled with an experience of internet connectivity. Lin writes:

In mid-June, one dark and rainy afternoon, Paul woke and rolled onto his side and opened his MacBook sideways. At some point, maybe twenty minutes after he’d begun refreshing Twitter, Tumblr, Facebook, Gmail in a continuous cycle — with an ongoing, affectless, humorless realization that his day “was over” — he noticed with confusion, having thought it was a.m., that it was 4:46 p.m. He slept until 8:30 p.m. and “worked on things” in the library until midnight and was two blocks from his room, carrying a mango and two cucumbers and a banana in a plastic bag, when Daniel texted “come hang out, Mitch bought a lot of coke.”

When confronted by hyperactivity, it’s easiest to be passive, to sway against its tides.

Months later, having just graduated from college, jobless and decidedly “surfing couches for a bit,” I hear Car Seat Headrest’s Teens of Denial and, frankly, it helps me a lot. Our own Rob Arcand relates it to the “now-unfashionable texts of Alt Lit figureheads like Tao Lin, Mira Gonzalez, Melissa Broder, and others,” by lending it the same descriptor they were given: New Sincerity. Teens of Denial is oversaturated with expressions of disaffection, hopelessness, self-disappointment, and aimlessness delivered with well-calculated detachment. When a listener receives the recursive singalong hook to “(Joe Gets Kicked Out Of School for Using) Drugs With Friends (But Says This Isn’t a Problem),” they can’t be sure on what level they must take it: “drugs are better with friends are better with drugs are better with friends…”

It’s a simple line and, in its context, can easily be judged as tragic. Nonetheless, I soberly take it as a maxim for relation, a reminder that shared experiences of any form and quality really do surpass our obligations to having and appearing.

I often think about an article my friend Ty shared on Facebook something like two years ago. I’ve searched it and re-searched it, read it and re-read it again and again since then, always thinking I’ve finally put it to rest. It’s called “We Are All Very Anxious,” and it was published by the organization Plan C and the Institute for Precarious Consciousness. Its subheading is “Six Theses on Anxiety and Why It is Effectively Preventing Militancy, and One Possible Strategy for Overcoming It” and its argument is thorough, nuanced, and too refined to do proper justice here. In short, however, it claims that “[i]n contemporary capitalism, the dominant reactive affect is anxiety,” and that this is a public secret, which is to say that it is “something that everyone knows, but nobody admits, or talks about.” Thinking back to my own dependency on (and eventual aversion to) Facebook, Ratliff’s coping with musical hyper-availability, and Obama’s nightly repose away from company, I consider the following that Plan C has to offer:

Today’s public secret is that everyone is anxious. Anxiety has spread from its previous localized locations (such as sexuality) to the whole of the social field. All forms of intensity, self-expression, emotional connection, immediacy, and enjoyment are now laced with anxiety. It has become the linchpin of subordination. […] It is difficult for most people (including many radicals) to acknowledge the reality of what they experience and feel. Something has to be quantified or mediated (broadcast virtually), or, for us, to be already recognized as political, to be validated as real.

The public secret functions on the predicate that feelings are insufficient as sources of meaning. Artists, musicians, writers must acknowledge this and interrogate it if they wish to radically exhibit the nuances of feeling and rethink forms of political art. Perhaps art, so long as the art under interrogation is non-presumptuous and hazard-less, is the one field in which one should never need to make claim of their validity. Perhaps self-gratifying art will always be understandable.

2016 has been marked with constant news of denied validation to many: the DAPL battle, the Brexit decision, the unending stream of racialized police violence in the US, and the general narrative and outcome of the US elections, to name the most prominent examples from my point of reference. When facing such denial, it helps to remember that each of us is valid and can act in a multitude of ways. When Trump was elected, I felt powerless and ashamed. I joined others in the streets of Los Angeles, which felt good, but didn’t always satisfy the lowness that I woke up with for days and days. I felt small and silent. My hope is that, in the wake of an election that proved in part that loudness, performances of surety, and self-righteous hate speech could be so easily exploited within politics, it will become increasingly valuable to embrace introspection, nuanced uncertainty, and intimate vulnerability, executing these traits by means honest to our goals.

More about: 2016, Car Seat Headrest, Christian Wolff, Frankie Cosmos, Kero Kero Bonito, Michael Pisaro

We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music that helped define the year. More from this series