It’s a rare historical experience to witness the birth and rapid maturation of an entire art form, but that’s exactly what happened with film in the space of little more than a century. Movies have carried our collective narrative for several generations, largely usurping literary fiction and theater as our primary medium of storytelling.

Film evolved into the creative medium perhaps best suited for the manipulation of time: the flashback, the dream sequence, and the split screen stretch and compress time with a precision rarely achievable in older media formats. New techniques to control audience focus exploded into practice as well, with closeups, panning, and bridging giving rise to a new symbolic language. These techniques arose quickly, appearing in some of the earliest film shorts from filmmakers like Edwin Stanton Porter and George Albert Smith.

But a fundamental expressive weakness loomed over early cinema: there was no way to reproduce synchronized sound. Dialogue and narrative had to be conveyed through exaggerated gestures, written “title cards,” and props with large written labels. By the late 1920s, “talking pictures” became technically achievable at last, with simultaneous dialogue and action on-screen. Music, which had been presented through live piano or chamber orchestra accompaniment, could now be directly integrated into the experience as well. And as it happened, a fledgling Walt Disney Studio in Hollywood, led by a core staff of Kansas City expatriates, was experimenting with new animation techniques around the same time.

The Silly Symphony Collection 1929-1939 is a 16LP box set from Walt Disney Records and Fairfax Classics that documents in full this early confluence of cinematic sight and sound. Before movie studios became corporate monoliths, before regimented demographic research and press junkets, and before product placement and viral marketing, the discipline of scoring music for film largely began within this series of 75 animated shorts. The early Silly Symphonies are fundamentally experimental works — single reels of five to 10 minutes in which new ideas could be workshopped and then integrated into later feature film productions if they proved successful. The release of this box set marks the first time in history that this music has been available as a strictly audio presentation, making this an important moment for further study and appreciation of these urtexts of film music.

Carl Stalling

Several prominent film composers contributed their work to the Silly Symphony series, but it was the legendary Carl Stalling who brought the concept to Walt Disney and scored the introductory year of the series. Stalling had come to film music through the earlier discipline of live accompaniment: before synchronized sound, music was provided by pianists or small ensembles who played familiar, mood-appropriate themes during screenings. This was a primitive, partially improvised process whose success depended largely on the performance skills and aesthetic sensibilities of each accompanist. With a goal of bringing more consistency to screenings nationwide, a few tools of the trade were developed around this time. These included fakebooks with familiar themes, organized by mood or dramatic potential, and basic cue sheets for suggesting what pieces might work well for a given film, complete with tempo and duration indications to match on-screen action. The earliest recordings made for film followed this practice, with music being produced to a finished edit of the movie.

Stalling had produced scores for several Disney productions in 1928 and early 1929, but he proposed a revolutionary concept for the Silly Symphony model: music would be arranged and recorded first, working from a rough storyboard, and the animation would be completed to the score. Cue sheets were exchanged for “bar sheets,” providing rhythmic direction for the animation staff. Disney saw this as an opportunity for his animators to further develop their own technique. What started as an experimental practice went on to become the standard procedure for most animated films to this day, wherein dialogue and most music are recorded first. Further enhancing the technical precision of his recorded scores, Stalling conducted first with a metronome and then with a click track, which in that era was a physical product of punching regularly-spaced holes in a filmstrip so that the conductor could monitor the tempo via headphones.

Much of Stalling’s renown as a cartoon music composer is indebted to his astonishing Warner Brothers-era scores written for the Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies cartoons in the late 1930s to the late 1950s, but hearing his early work for the Silly Symphony series is a revelation. In “The Skeleton Dance,” the first Silly Symphony from 1929, Stalling’s iconic sense of timing and phrasing arrives fully formed from the first minute. A woodblock-, vibraphone-, and string-dominant arrangement of Greig’s “March of the Dwarfs” is the centerpiece of this score, but Stalling’s original writing around the theme is perfect: ambitious, imaginative, and full of delightful tempo shifts, stop-time passages, and unexpected turns.

The same holds true for the other six Silly Symphonies scored by Stalling, which comprise the first LP of this box and the start of Disc 2. This is truly foundational music, a model for subsequent composers’ contributions to the Disney series and a catalyst for a broader symbolic language of film music that continues to the present day. Many of the early Symphonies are animated dance numbers, but a few incorporate short narratives, initially following the seasonal behavior of animal characters. These short stories are where the Stalling vocabulary fully asserts itself: the swooping and racing of legato string passages, the sneaking and lurking of low pizzicato quarter notes, slide whistles of surprise, percussion bursts of dramatic confrontation, tempo shifts that change on-screen direction, vibraphone interruptions at confused pauses. Stalling’s musical effects have since become so ubiquitous that the listener can imagine the plot and action with no screen necessary.

Bert Lewis and Frank Churchill

Upon the departure of Stalling, composer Bert Lewis was brought to the Silly Symphony series. Lewis knocked out eight post-Stalling charts to finish out 1930, staying close to the Stalling model of cleverly intertwining three or four familiar melodies per score. While most of the Lewis scores feel a bit more cautious than Stalling’s, his musical personality became apparent by the end of the year in an intense arrangement for “Playful Pan.” An intriguing mix of lighthearted Tin Pan Alley vibes and heady, ominous transitions, Lewis’s composed sections for this mythological adaptation employed chromatic, whole-tone, and diminished runs that were very hip for 1930, presented with a delightfully bombastic percussion approach.

Composer Frank Churchill joined the Silly Symphony music team in 1931. His scores initially were similar to Stalling and Lewis, but he worked from a perspective closer to that of a “songwriter” than a “composer/arranger,” with a penchant for memorable melodies. Over several years, his scores were steeped in more original material and relied less on familiar themes. His score for “The Bears and Bees” (1932) featured almost entirely original music with imaginative arrangements, including mallet percussion runs that would have sounded right at home on a Frank Zappa record.

By 1933, Churchill’s melodic strengths as a songwriter netted the Silly Symphony series its first and only big commercial hit: “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf.” The centerpiece of the “Three Little Pigs” Symphony, it went on to become an iconic anthem of the Depression era. Though the Silly Symphonies were designed as one-offs with no recurring characters, Disney attempted to capitalize on the surprise success of the song with three sequels: “The Big Bad Wolf” (1934), “Three Little Wolves” (1936), and the penultimate Symphony “The Practical Pig” (1939).

Leigh Harline and Albert H. Malotte

While Churchill continued to score occasional Silly Symphonies, composers Leigh Harline and Albert H. Malotte wrote the scores for much of the latter half of the series. Both had relatively formal music backgrounds compared to the live accompaniment resumes of their predecessors, and this was evident in their polished scores. By the halfway point in the series, the core dialect of the music had transitioned from experimental to familiar, and the a larger studio orchestra had become much more confident performing this demanding music. Recorded dialogue and singing were added, taking some of the Silly Symphonies into opera territory. The Harline/Malotte era was marked by a new sophistication and subtlety.

Though he doesn’t have the contemporary name recognition of Stalling or Churchill, Harline’s music is consistently the best in the series. Whatever he might have lacked in bombast and innovation is more than repaid with a deep understanding of orchestration. Even his earliest Silly Symphony work, like his collaboration with Churchill on “Lullaby Land” (1933), introduced a new level of contrapuntal thought in the introduction, with many later passages that wouldn’t be out of place on a Mr. Bungle record. While Harline’s music was often playful and fun, he also handled terse and tender moments with sensitivity, tackling darker subject matter like the Rape of Perspehone from Greek mythology in “Goddess of Spring” (1934). Other pieces like “Music Land” (1935), an “epic battle” between classical and jazz music, likely resonate more with the benefit of time. Redolent of the high-concept stylistic mashups of the NYC downtown scene in the 1980s, the score features a music-genre wedding ceremony near its conclusion that employs a bizarre instrumental recitative/sprechstimme technique. Some of the best musical moments of the whole series arrive in the Harline score for “The Pied Piper” (1933), an all-original score packed with sophisticated rhythms, dizzying tempo and style shifts, and an extremely wild ensemble flute riff that sounds more psychedelic than a Timothy Leary speech.

Malotte’s scores appear only in the last few years of the series, which is a shame. Though his work isn’t as immediately exciting as Harline, he demonstrates a steady hand and a classical sense of orchestration, exemplified in the modern avant-garde breathing sounds and pointillistic lines of “Broken Toys” (1935). His best overall score for the series appears in “Moth and the Flame” (1938), an excellent mashup of pop melodies, light dance styles, and downright furious symphonic writing. The circumstances behind that symphony suggest that he may have arrived too late for the opportunity to mature as a Silly Symphony composer, however. The animation for “Moth” was in development for three years before the music was completed, suggesting that the original music-first production concept established by Stalling had been reversed in at least some cases as unfinished/abandoned projects were revisited in the twilight of the series.

Presentation

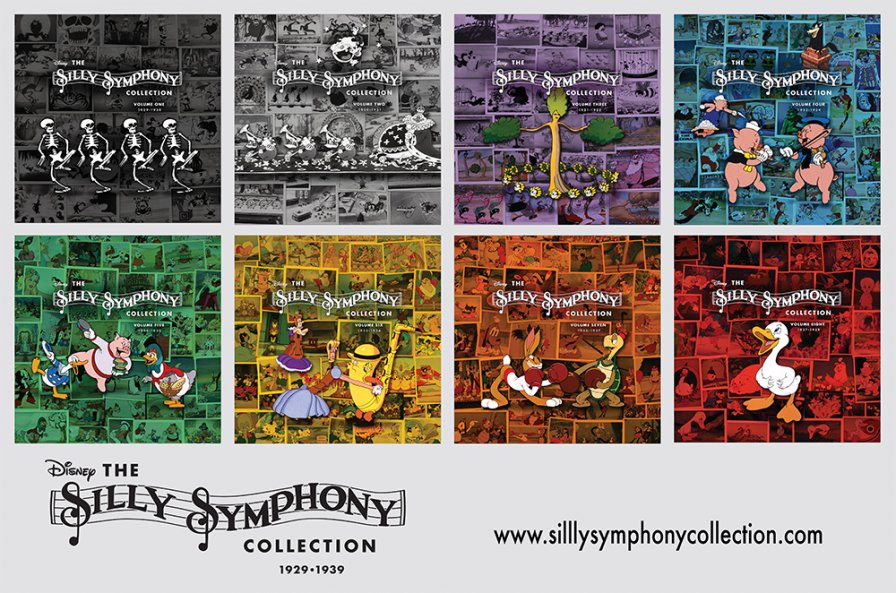

The Silly Symphony Collection is lavishly packaged in eight heavy gatefold Stoughton jackets, all contained in a classy clothbound slipcase. Animation stills are collaged as artwork for each jacket and cleverly transition from black-and-white to color images with the introduction of Technicolor within volume 3 (1932). Instead of a book, the insides of each gatefold contain detailed liner notes from Disney historians J.B. Kaufman and Russell Merritt. Production notes for each Symphony, including musical director and lists of compositions quoted in each score, are detailed on the back of each volume. Though the sound quality naturally varies over the course of the series, Disney producer and historian Randy Thornton has done a great job bringing detail and warmth out of these ancient recordings to the greatest extent possible, and the vinyl is quiet and crisp.

My only quibble with this box is the liner notes. While Kaufman and Merritt have literally “written the book” on the Silly Symphony series (see their Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies: A Companion to the Classic Cartoon Series for even more detail), they approach the material as film historians, as opposed to musicologists. Toward a deeper relationship with this music, both perspectives are invaluable. More scholarship should be done to further investigate the broader context for this music, as it occupies an important developmental state between the Wagnerian leitmotif and contemporary sampling/remixing practices. Now that it has been made widely available through this box set, hopefully that conversation can begin on solid footing.