Dominick Fernow’s “collage project” Prurient has been getting a lot of attention after the release of his Hydra Head debut Bermuda Drain, but not all of the attention is positive. A frontman of the so-called noise scene and head of New York City label/retailer Hospital Productions, Fernow has boldly tread through new territories of sound and melody with his new releases, which has brought about confusion with noise purists who have an insatiable desire for tradition/comfort within a realm of musical expression that largely defied tradition and comfort in its early forms.

We spoke with the man behind Prurient about his new 12-inch EP, Time’s Arrow, his new directions in sound, and the long list of misunderstandings that follow him.

There’s a lot of talk about this “new turn” with the Prurient moniker with the release of Bermuda Drain, with some fans expressing disappointment that it’s not a “noise record.” Would you say it was really that great of a shift? To me, it seems no more melodic or musical than Cocaine Death, just perhaps less buried in noise. Would you describe this perceived change as a slow progression or as a sudden shift?

I think that you’re right in a lot of the sense that it’s not really that new. I’ve been working with melodies and synthesizers for years. The idea is the same in terms of what sounds are being used, but the hierarchy of the sound is reversed and new. Whereas before, the melody would remain in the background, now it’s kind of in the foreground. Noise becomes more of a texture and an atmosphere rather than a lead element, too, but the biggest change for me would be the clarity of the voice. We originally tried to do all the vocals completely clear with no effects whatsoever and do them all in one take. That didn’t work at all, but it was an interesting experiment to see how to handle voice without all the effects. I basically had to relearn how to speak.

So it’s ironic in the sense that it was supposedly trying to strip away the affectations, but in reality it created a hyper-conscious awareness of my actual voice and how that would translate onto recording. There’s an extreme stiffness in the vocals that I think never existed before, as they were wilder in the past. And the equipment usage was also totally new, although you’re not wrong in making the links to the past. It’s also ironic because the guy that I worked with heavily on the album, Kris Lapke — he has a project called Alberich that’s entirely beat-oriented industrial music, and I’ve been doing stuff with Vatican Shadow for over a year. So it’s funny for me to see people’s reaction to the new Prurient material as totally criminal and unacceptable, but at the same time these are the very same people who love and follow the Vatican Shadow and Alberich projects for having beats and melodies and being “noise free.”

“When all the people our age and older are dead, and all that’s left are the people who have grown up online, I’ll be glad that I’ll be dead at that time.”

Yeah, there seems to be a lot of noise purists with rigid standards.

Yeah, and that’s really sad to me, because it used to be the opposite. Noise used to be a place that was devoid of expectations, but there are people who have been working 24 hours a day to make it into a genre of music like any other with a set of rules and regulations, which to me is the antithesis of noise ideology. So I have no problems with not being categorized as such, because that word has come to mean the opposite of what it should. Ultimately, at the end of the day, I’m making sounds that I want to hear, and that’s really the main thing that’s important within that kind of philosophy that originally drew me to it: the total selfishness of creating your own world and only doing it for yourself.

It’s interesting that you said that, because I was going to ask you about a previous interview that you did for Noisecreep, where you explained that you don’t make music, you make noise. I wanted to ask you about your writing and recording process, and if it was an entirely individualistic experience or if you remain conscious of the audience that will ultimately receive it. In other words, do you ever attempt to create something aesthetically pleasing?

When I say that I make music for myself, it’s true, but that doesn’t mean that there’s no audience consideration. It just means that the audience doesn’t influence any decisions. If you’re going to play shows and release records to the public, then by definition you’re addressing the audience one way or the other, but that doesn’t mean that they control the results. It just means that they’re there and that their interaction is a part of it. I would say that, for me, it’s important to draw the distinction between something that’s music and something that’s musical. I would say that I am an artist that uses music and sound; I would never say that I am a musician, although Prurient may be musical in that sense. The intent is not to create music, in the sense of an exclusive sound experience. The intent is to use the idea of sound or music as a platform for the communication of the subject matter and to provide a context for the imagery, content, the lyrics, the performance, etc.

However, I will say that I’m more and more drifting away from the idea of trying to participate in the so-called music scene, as I feel that there’s not enough emphasis or appreciation of content. I think there are too many people that have an attitude of “Oh well, if it sounds good, then it’s good, and I like it, and I don’t care where it’s from or who’s making it or what they have to say.” And there’s kind of a literalism to the approach toward subject matter that I find incredibly uninspiring and unsophisticated, frankly. If you use something about serial killers, then the only possible explanation is that you’re a serial killer or you want to be. If you address drugs, then you must be using those drugs, and so on and so forth. People associate music with identity so much to the point where they’re unable to separate the image that’s supposedly being promoted by the artist and the sound in any other way than at face value, and I find that extremely frustrating.

Along with the false controversy of Bermuda Drain’s sound is this sudden need to assign agency to your involvement with Cold Cave as a direct influence on your current direction.

Yeah, and that’s another thing that I don’t understand, why people would think that they’re somehow discovering a conspiracy that my involvement in Cold Cave would somehow influence my work as Prurient. Prurient is a solo project that is a reflection of my life that I’ve been doing for years, and I’ll probably be doing it until the day that I’m dead. So, concerning the fact that I’ve been involved with Cold Cave for almost five years and have done hundreds of shows and thousands of hours of touring, I don’t understand why people are patting themselves on the back for making that connection. Of course it’s an influence. No shit. I would also say that I’ve influenced Cold Cave. Wes and I have worked together intensely for years in a variety of ways. It’s hard not to be influenced by people that you spend 24 hours a day with for months on end. In a more direct sense, I’ve certainly learned more about electronic music and working in a studio because of my experiences. I just don’t get the insistence on drawing that point when it seems so blatantly obvious. It’s not exactly like I’m operating in Cold Cave under any sort of anonymity. And furthermore, Wes has played the only shows with me as Prurient this year since Bermuda Drain has come out.

“Noise used to be a place that was devoid of expectations, but there are people that have been working 24 hours a day to make it into a genre of music like any other with a set of rules and regulations, which to me is the antithesis of noise ideology.”

How would you describe the new 12-inch, Time’s Arrow, as a follow-up to the last LP, Bermuda Drain? Is this a continuation for you or a next step?

I would say while Bermuda Drain focused more on melody and atmosphere, Time’s Arrow is more related to texture and dissonance. Originally, all of the tracks on Time’s Arrow were going to be on Bermuda Drain, and it was going to be a double album. I made the decision to divide them into two separate releases, because I felt that it was such an enormous undertaking to create a project using entirely new equipment, which was a very long process of discovery for us. We would get somewhere and have a breakthrough and think “oh this is it,” and then a week later we would have another breakthrough, and it would make everything else diminished. So as we went on, we just kept revising, building, changing, redoing, and editing, and it became clear that there was really two sides to the album. I felt that, by dividing them, it was a gesture towards emphasizing the dynamic in a way that wasn’t necessarily hitting the audience over the head so much as it would by sitting down and listening to a record with this one smooth kind of techno song and then a really brutal noise track, and a quiet song and a loud song and a quiet song and a loud song. That kind of special effects on an album, I think, is really tiring and takes away from the ability to enter into a world. So I made the decision to divide it into halves, because I think that when you try to say everything at once, sometimes you end up saying nothing. I didn’t want to make excuses for Bermuda Drain. I knew a lot of people would be startled by how melodic it was, how clear it was, and how electronic it was. I didn’t want to be like, “Hey, look, I’m still making noise guys.” I didn’t want to have that disclaimer. We chose to release the Bermuda stuff first to avoid having any apologies.

Could you talk some about the concepts of the new EP? I have heard that it’s based on “the Black Dahlia” murder and Martin Amis’ novel Time’s Arrow.

Unfortunately, it’s actually totally incorrect that the record has anything to do with the book under the same name. Sadly it was disseminated as such by a reviewer, and it actually has literally no connection whatsoever. Although it may be an obvious one to draw, there’s no attempt at that.

It does reference the Black Dhalia murder, but not in any sort of literal way. The name “Time’s Arrow” comes from a book on wormholes and blackholes and addresses the idea of entropy in our brains and entropy determining the way that we perceive events and time in a linear fashion. The chapter on “Time’s Arrow” basically said that if we didn’t have entropy, if we didn’t have the process of decay in our brains — mind you, this is all theoretical — then we would not be able to perceive time in a linear fashion. It gave an example that we would see a deck of cards reshuffling themselves. We would see coffee being poured back into a pot, and we would see smoke reversing back into the tip of a lit cigarette. And it scared the shit out of me when I read it. I felt that it was related to an experience that I had with a woman who I was living with for years who decided one night that she wanted children and would move to Los Angeles. So here’s a person that I spent years with who basically disappeared from my life overnight. So the idea is more of a metaphor for information loss, that feeling of things being unresolved or unsolved, and not knowing and becoming very familiar with something that you don’t actually have a clear picture of. So it’s kind of a metaphorical poem about loss, mystery, the unknown, and knowing someone is there but not having any communication with them. In a sense, there’s this sort of a death that takes place in our lives when these relationships and events suddenly change. And even in real deaths themselves, the line between life and death is minuscule. The line between knowing and not knowing is minuscule.

I was very disappointed that the information went out that it was about the novel, because it had absolutely nothing to do with it. I mean, it’s a perfectly fair assumption to think that the two could be related, but they’re not.

Time’s Arrow will be your second release for Hydra Head. How would you say the releases for Hydra Head differ from, say, your recent cassette releases on your own Hospital Productions this year, like Despiritualized or Reflective Tile Inside The Tunnel?

There’s always been a separation, kind of, in the sense of the more private, direct, gesturally documentative work of the cassettes than the larger statements of the vinyl albums and CDs. I don’t think that there’s necessarily any difference from any of the past releases that have been full-on major releases, like the stuff on Load, for example. I don’t believe in the quality of releases. I think some things are meant to be limited and obscure and more personal and other things are meant to be larger and more ubiquitous. They’re all building toward the story, but there’s a process and an intent that takes place within each medium. Recording to tape is an entirely different experience than recording to a computer.

Like getting back to this idea that these purists are out there, Prurient is not a puritanical project. It never has been. It’s always existed to serve the moment. If I feel there’s a need to record something small, fine. I don’t think that everything I do has to be heard by everyone. Getting back to this idea of time and information loss and mystery and sequence, I think that one of the saddest parts about the time we live in, the information era, is that there is an attempt to answer every question immediately. I think when you do that, you’re really losing the pleasure and experience of investing into something. It used to be that you would go into the record store and you’d have heard about a band, and maybe the first record you get from that band wouldn’t be the classic record. You’d get some weird latter-period Bad Brains record first, and that would be your first experience of Bad Brains, having never heard Pay to Cum. I think that’s a great thing. I think that builds a personal experience for a listener that can go against and challenge and enrich your expectations. If you heard about Black Flag as this punk band, and then the first thing that you get is Family Man, because that’s all you can find, that’s an entirely different experience than what your expectations have led you to believe. And I think that’s great. I think that it’s great not having all the answers, because you start thinking for yourself, asking your own questions, and trying to understand them. And that’s part of the whole fun of music and art: not that you know everything about everything, but it’s that you don’t know, and that’s why you’re investigating, to learn something, to share something. So, I continue to do these more limited, private releases, and I think that it’s okay that not everyone has them or has the complete picture. To me, that’s more interesting; to me, that makes something worthy of investigation. It challenges the individual listener on this ongoing story or search.

In the pre-internet days, that was actually possible. Now every single tape is immediately online illegally within moments of it being released, which is an incredible disservice to not only the art, but to the people getting the material. I feel sorry for the children today who don’t have the pleasure of really going on the hunt for music and art. It’s like reading the last page of a book first. I think it’s really going to have massive cultural ramifications that we can’t even anticipate yet. When all the people our age and older are dead, and all that’s left are the people who have grown up online, I’ll be glad that I’ll be dead at that time.

“I think some things are meant to be limited and obscure and more personal and other things are meant to be larger and more ubiquitous.”

I completely agree with you. The current state of how people come to music is really discouraging to me, but I don’t know if I’m just being nostalgic.

I don’t think it has to live in a world of nostalgia. I think that it’s more about literally the way things are being consumed. It’s like eating and digestion. If you get a gigantic plate of food that’s too big for you and try to eat it all as fast as you can, then you’re not going to be able to correctly digest the material. There’s this obsession with quantity over quality, and I think that the absolute epitome of the internet is “well if I can hear every album from a band in one day, then why wouldn’t I?” And I just feel sorry for people experiencing music now like that, because it’s no longer really an experience. It’s just consumption. To me, music and art used to be the escape from a consumer society, not the main root of it.

The most disturbing element to me is the sense of entitlement that has been cultivated. It’s no longer an argument of “should I?” but just “I can, so therefore I will.” At the same time, [Hospital Productions] is offering tapes digitally that we release now, and I think that we’re one of the first noise labels to do so. I ask the artist if they want their material to be available legally online. It’s no longer an issue of “do you want it?” It’s already there. It’s just more like “do you want to have any control in the matter?” And it gives people, who do want to support the artist instead of disgracing their artwork, the option to do so.

How has the new material translated into your live performances?

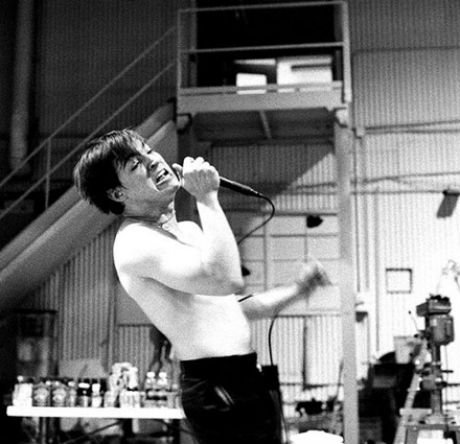

I’ve been performing with another member, and that’s not necessarily new, as I’ve actually done several performances with other members over the years. It creates a triangle of the experience. Rather than just me and the audience, it’s now me and the audience and this other person, and that’s an entirely geometrically different dynamic for the visual aspect of a performance. Sonically, we’re trying our best to translate the material from the new album live. By definition, playing live is essentially a prescribed experience. There’s a time that you go on, there’s a stage, there’s an audience, you face them, they face you, etc., etc. And you’re basically trying to make people believe that what they’re seeing is authentic or real, and maybe it is. But that’s the challenge about performance, to overcome the stiffness and lack of surprise that the whole event is defined by. I don’t think it’s an easy thing to do, and I don’t think I’ve done it enough yet. It’s something that will continue to evolve as the sound and music evolve. I have some plans moving forward to try and communicate more of the content and subject matter and less of the sound live. So there are no future performances booked at this time, and I hope to change that with an even newer live show.

I’m sure everyone will be excited to see that. So are there any final thoughts or anything needing attention that I may have overlooked?

I would just like to reiterate that I don’t consider Prurient to be music. I consider it to be a collage project that uses music and sound, and all of the elements are of equal importance. And I guess in one last response to some of the analyses that I’ve seen and that are totally inaccurate, ultimately it may be focusing on the youthful energies of rhythm and melody, but essentially Bermuda Drain addresses adult subject matter. It addresses the issues of marriage, children, and the life rituals of society. It has nothing to do with youthful ideas. That would be it.