Willie Lane is one of my favorite living guitarists. I liked his 2009 album Known Quantity so much that I voted for it as one of my top albums of that year in Village Voice’s Pazz & Jop year-end critics poll. Nobody else voted for poor Willie, but Known Quantity ended up tying for 937th place with about 300 other albums that probably deserve to be closer to the top of the list. Oh, well. As the wise man who visits me in my dreams always says, “Aesthetic justice is something only fools hope to find in the real world.”

Lane, a 30-year-old picker currently based in Philadelphia (but moving very soon to Western Massachusetts), plays an extremely loose, primal, noisy type of improvised and extra-heavy dirt-blues. He first popped onto my radar with Recliner Ragas, released in 2006 on Matt Valentine’s Child Of Microtones label. It’s a gnarled gem — pure grit. Same goes for everything he’s released since. But Willie doesn’t release much music into the world, so when he quietly dropped the follow-up full-length to Known Quantity a few months back, it was a very pleasant surprise.

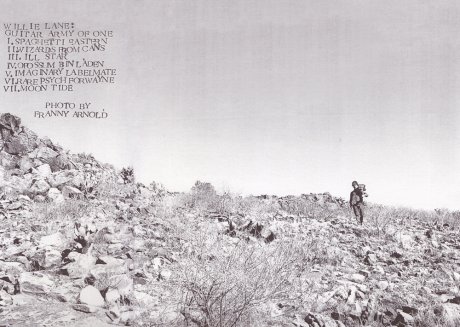

The name of the new album, released on vinyl on his Cord-Art label in an edition of 350, is Guitar Army Of One. It’s lovely and jangly, with bizarro screeches and boomy kraangs at all the sweetest spots. I caught up with Willie after he got off work recently at the University Of Pennsylvania’s Van Pelt Library. We talked about as much as we could talk about in 45 minutes, because we were both hungry for supper.

You just walked out of the library. What were you doing in there?

I do a lot of the physical processing of the books and DVDs and things. I put the stickers on them. It’s not too demanding.

What’s the highlight of your day?

It depends on what sort of music I bring to listen to — there’s a lot of headphone time — and how witty the emails I get from my friends are. And lunch. Lunch is definitely the pinnacle.

What music did you bring to listen to today?

I listened to a lot of Hatfield and the North on Youtube, and I listened to The Zombies’ Odyssey and The Oracle. Oh, and I listened to the Book Of AM. It’s this early-1980s psychedelic record made in France, I think. It has some relationship to Daevid Allen and Gilli Smith from Gong. I don’t know if they play on it — they might have just been friends. It’s somehow related to that axis.

Do you own a lot of records?

I do. My collection’s all over the place. Jazz, noise, pre-war blues. I’m actually going to the Brooklyn Flea this weekend to sell some of them. I’m moving to Easthampton, Mass., in a few weeks, so I need to get rid of some stuff. My living space in Philadelphia right now houses it, but the future living space might not be so accommodating. I’m preparing. I wouldn’t mind lightening the load by a few-hundred pounds.

I’m like a nation at peace. I’m an army made out of one guy who is at his best a security guard.

Why are you moving?

I’m making a career change. I’m tired of putting stickers on books, and just looking forward to lunch everyday. I’m going to study cabinetmaking at this school called the New England School of Architectural Woodworking. I wanted to do something a little bit more engaging, and something that involves a skill. It seems practical. People get jobs pretty easily after graduating. It seemed like a good way to change directions, and do something radically different.

Have you done much woodworking in the past?

I messed around with stuff when I was a kid. I’ve hammered boards together and made book and record shelves at home. I always enjoyed doing that. I’ve generally done more physical work in the past, and I miss that. I have a problem with sitting in front of a computer all day. That life’s not for me. I’d rather be active. I spend a big hunk of the day now looking into a computer. For a while I was studying Library Sciences, and it was way too much. I started to get square eyes. It seems like the world — or at least the developed world — is trying to corral people into these jobs where they just stare at screens.

It’s painful. I do it all day, too. That aside, let’s talk about music. You grew up in Maine, right? When did you start making music?

I grew up in Bristol, which is about an hour from Portland. I started playing when I was about 12. I took guitar lessons, but before that I wanted to play drums. But no parent really wants to buy their kid a drum set. That didn’t happen. So I started playing on an acoustic, and learned to play stuff like “Stairway To Heaven,” “Johnny B. Goode,” Sabbath riffs, and all those things beginning guitarists learn.

Whom did you take lessons from?

Some local guy my Mom knew. He was very cool, in retrospect. He didn’t shove anything down my throat, and taught me what I wanted to learn. He had the patience to show me things that I wanted to learn, like Black Flag songs or whatever.

When did your playing start to diverge from the Zeppelin stuff?

It took a while. I probably didn’t start developing a personal style until I was in college at Hampshire. I played in a hardcore band in high school, but I didn’t feel like I had control over the sounds I wanted to make until college. That’s when my music taste evolved. I started listening to improvised music, and free jazz. Those things broke down the idea that there is a right and wrong way to play guitar. I learned that you could do feedback for 30 minutes, and that that was music, too. That was a big revelation for me. Once those old ideas were broken down, I started to rebuild.

Did you study music at Hampshire?

Not really. It was not something I really enjoyed. I took music classes that were more like The Social History Of Rock ‘n’ Roll, and stuff. I didn’t really study music theory. I can’t read music, and I can barely read tab. I’ve been thinking about learning some straightforward country-and-blues songs for technique purposes, but I’ll probably cheat and just watch a YouTube video about it instead.

The other day I was trying to tune a banjo, couldn’t remember how, so I went straight to YouTube.

Yeah, it’s scary. The next step will be a hand that just comes out of the screen and turns the pegs for you. Or some brain in a vat thing where you just get the sensation and pride of having played something without having to actually play it.

Oh, I hope so! But back to Hampshire. There’s a lot of strange music happening around those parts. That must’ve been a big change from Bristol, Maine.

Totally. In Bristol, it was hard finding people who were into music that wasn’t on the radio, or that you couldn’t find in a Columbia House catalog. An obscure band would’ve been Sonic Youth. I was already into stuff like Albert Ayler, and a lot of noise, but when I went to Hampshire, I was so surprised to find other people who know about that stuff. I made some great friends, and it was a very nice community of people who are all very serious, thoughtful fans of music.

One of the people you connected with was Matt Valentine up in Brattleboro, Vt. How’d you meet him?

I was a fan of his music, and I got to know him as a fan first. Matt sort of took me under his wing, and encouraged me to do solo stuff. He asked me to do a CD-R for his label, Child Of Microtones, and he had me play a show or two. I was mortified to play solo at first, and I still don’t like to do it. I’ve never gotten used to it. Matt’s very responsible for getting me to go out and play. I didn’t have the courage to do it on my own.

And that was Recliner Ragas, right? Was that your first solo recording?

Yeah, it was, in 2003. I went up to Matt’s house for the day and spent the night — I had no prepared material when I arrived — and I just played guitar. He just rolled the tape. He has his own way of recording things. He has some treatments and effects that he applies, and some unorthodox mic placements. He has a bunch of funny mics that friends have built him, and he places them in various spots of the room. He edited the album, so, to me, it’s more like a collaboration. It’s almost like a Fripp & Eno thing. I just played guitar, and he had as much say in the final product as I did.

I learned that you could do feedback for 30 minutes, and that that was music, too. That was a big revelation for me.

Were there any overdubs or anything?

No overdubs. There’s one track where Erica (Elder, a.k.a. EE) was playing a flute, or a shruti box. He just rolled tape the whole day and night, and then the next week sent me a master that he’d edited down. I provided the raw material, and he distilled it. It’s just instrumental music that doesn’t have much of a structure, so you can just cobble it together to make it sound deliberate when it wasn’t. I have a dim recollection of playing, and the evening getting on. We had a nice dinner and plenty of refreshments.

Next you released Known Quantity in 2009, six years later. What took so long?

I don’t know. I guess I just didn’t get my act together. When I look back, I realize that I’m really slow. So much time passes between my recordings, which are very few.

Did you compose any of those songs in advance, or were they improvised?

Some of them started from composed riffs. I normally just lay down a riff on the tape, and then add stuff to it that sounds cool. I’m not trying to capture a composition on tape, but it’s more like injecting a tape with sound. There are a few overdubs, but not many.

I particularly remember this one moment from the album where there’s a nice, mellow, jangly riff, and then out of nowhere, a really loud electric lead bend comes in. That was great.

Oh yeah, I know what you’re talking about. I don’t remember what I called that song, though. It might be called, “Tired Pioneer Blues.” I thought that was amusing to throw that in there. I think that was actually inspired by the Shadow Ring, like a sense of humor inspired by theirs.

When you moved to Philadelphia, were you friends with the guitarist Jack Rose?

I was. Jack was one of my best friends here when he was still alive. He was a great influence. When he was here, I had just put out my first proper LP. We’d hung out for the three years up until his death pretty regularly, and he’d always bug me about when I was going to put out the next record. I obviously wish he was still around, now that I’ve become a bit more active. I’d love for him to hear my music. He always delivered the goods. He was a great performer. He put all his energy into it, right then and there on the stage.

Did you ever play together?

No, his skill was way beyond mine. He was a professional player. He could read music and everything. And I was just formless, and really feeling it out. Only recently have I tried to get better at finger-style playing. We wouldn’t have been compatible. He’s much better playing with guys like Pelt, or Glenn Jones, or the Black Twig Pickers. I shared bills with Jack and MV & EE a few times, but that’s it.

You referred to Jack as being a professional. Do you see yourself as more of a hobbyist?

I still consider myself a hobbyist on many levels. I don’t earn my living with music. I can go through periods where I don’t feel compelled to record or play — the guitar can just be some sort of release from daily stress or something. This is different from someone who feels really driven, whose identity, and primary mode of expression, is to play music. People like that have this fire, or desire to play, and it never diminishes. For me, there’s an ebb and flow. It takes me a few years to get a record together. Jack was a professional. That’s what he did. He’d play guitar for two or three hours every morning when he woke up.

Tell me about your new album, Guitar Army of One.

If someone collapsed Known Quantity and this record into one, I’d say it sounds like it’s from the same session. There’s no big leaps of progress made in technique or recording. It’s recorded on the four-track again. I guess it’s a bit more composed this time. There’s a lot more overdubbing, and I sculpted the sound a lot more as it was happening. I’d lay something down on the tape – composing it to tape. With the last record, I went back and listened to old tapes I’d forgotten, and then put some reverb on it or edit out a snipped that was good. For this record, I’d work on a track as soon as I recorded it, and flesh it out immediately. There’s also a lot more electric guitar on it. I had some nice fuzz pedals around that I wanted to use. I didn’t really think about it too much.

Once those old ideas were broken down, I started to rebuild.

For every song on the new album, are there five songs that didn’t make the cut?

Not really. I do have a lot of tapes, and I don’t know what’s on them. But this time, I knew immediately, while I was making it, what stuff I liked. Normally, I forget about something I record, and then go back later and realize I like it. This time, I was excited about the stuff I was doing, and I had a vision for it.

There are some humorous song titles, like “Opossum Bin Laden.”

We have possums in our yard that terrorize the garbage bin, and the shed behind our house. He earned the moniker.

How do you come up with song names?

Well, they don’t come while I’m making the music, that’s for sure. They come when I have to make the label art and covers. They don’t always have anything to do with the music.

How’d you come up with the record title? Is it a Rhys Chatham reference?

No, but that’s funny you say that. It’s a play on the John Sinclair book Guitar Army, and Army of One being the U.S. Army’s recruiting slogan. I think the book was just sitting on my shelf and I saw it when I was trying to come up with a title. And I did all the music myself, so it felt like a good descriptor.

Do you think of yourself as a guitar army?

Maybe a defeated army that doesn’t see much combat. I’m like a nation at peace. I’m an army made out of one guy who is at his best a security guard.

The future: Are you gonna wait another three years to release another album?

I don’t know. I’d like to travel and play shows at some point, so maybe one day I’ll get my act together. Right now I’m uprooting and moving and changing and haven’t thought about recording. I have a feeling that once I get to Massachusetts, I might find myself with a lot of downtime. Maybe I’ll record. I’m not looking to flood the market or anything, but it would be nice to put out something every couple years. All bets are off right now.