A sprawling, folksy epic with a big heart, Beasts of the Southern Wild is the remarkable debut feature from director Benh Zeitlin and the Court 13 filmmaking collective. This densely layered film is a fable about grief, told through the wondrous gaze of a young girl named Hushpuppy (Quvenzhané Wallis). She and her father Wink (Dwight Henry) live in a harsh Eden, a remote bayou of southern Louisiana called the Bathtub, that they cling to with hardscrabble devotion. These names tip you off to the fact that we are still on the grid, but only barely, hanging onto reality — and America — by a wisp of land that threatens to sink into the sea. This is the margin, a border landscape of swelling waves and gristly animal bones, where every creature fights for survival, and Hushpuppy is no different. She has an innate, mystical sense of this, lifting animals to her ear to listen to their heartbeats; her language describes a universe getting “broken” or “busted.” Her fears are realized — and the delicate balance of her ecosystem threatened — by the arrival of a Biblical storm that will flood the Bathtub. One of the marvels of the film is how Zeitlin doesn’t allow the Hurricane Katrina metaphor to overwhelm the story, twinning the natural apocalypse with a personal one: Hushpuppy’s father is dying. In what Wink knows are his final days, he subjects Hushpuppy to a tough, cruel love intended to prepare her for survival on her own. Beasts of the Southern Wild is a story of how such love and survival twist and turn on each other, an American fable that celebrates one girl’s wild spirit while mourning an irrevocable loss.

Quvenzhané Wallis and Dwight Henry are both locals and first-time actors who anchor the film with the fierce, raw talent of their performances and by the cadence of their speech. Zeitlin operates much like a young Terence Malick, making liberal use of Hushpuppy’s narration and of shamanic images of nature that are beautifully captured on 16-millimeter film by cinematographer Ben Richardson. This mythical, innocent musing will grate on some viewers, and in its first act the film occasionally gets lost in the junkyard fantasy that Zeitlin and his team have built. But as Hushpuppy herself declares, “I wanna be cohesive” (a word that Zeitlin repeated at the screening I attended), and I think it’s an apt descriptor. The director has created an impressively complete story world, and several sequences are stunning in the way they marry language and emotion to visual imagery.

While the film is committed to emotion, Zeitlin is not sentimental — a crucial distinction in such a watery world. While the Bathtub is a somewhat colorblind community (where everyone raises their glass, and their children, together), the director is clearly aware of the tensions and politics that inform his story. A particular standout for me was a sequence at a refugee shelter, where Wink, Hushpuppy, and the reluctant Bathtub holdovers are sent, kicking and screaming against their will. The subdued sterility of the shelter is sharply evocative and jarring, reminiscent of Diane Arbus photographs as much as post-Katrina newsreels. When Hushpuppy reappears, hair combed and in a smocked blue dress, it’s a shock: I feared for a tamed and subdued Hushpuppy more than for the wild thing knee-deep in primordial ooze.

Even in his distress, the shelter can’t hold Wink for long, and he and Hushpuppy break out and return to the shattered remains of their home. From this point onward the film lifts to its moving finale, a graceful exit that had the audience in tears. Throughout the film Wink repeatedly tells Hushpuppy not to cry, and she remains stoic and dry-eyed in the face of very real terrors. She also faces down the film’s titular beasts, prehistoric creatures called aurochs that are released from the melting polar icecaps and eventually come tearing across the southern land. These enormous, tusked pigs are no match for Hushpuppy, the rarest of creatures herself: a fierce and feral heroine. She doesn’t just have an appetite, she tears into life with her teeth. Still, the sweetness that mists the entire film can sometimes obscure Wink’s stubborn denial that his daughter is in fact not his son (he calls her “man” and says she’ll be “king” of the Bathtub). In one of the film’s most potent scenes, Wink gives Hushpuppy a drink, has her flex her biceps, and asks her, “Who the man?” Her ferocious reply is, “I the man!”

Wink knows how to shove Hushpuppy from the nest, but the absence of her mother Marietta is an unspoken grief that the film evokes in visual ways. Hushpuppy hangs her mother’s basketball jersey on a chair, as if the woman will appear to fill it, and lingers on the few memories she has of her mother. Those recollections are lovely scenes, framed so that we never see Marietta’s face. She is a woman of prodigious hips, and of heat: a hunter who can kill while half-dressed, the shotgun blast leaving her panties stained with alligator blood. When a bereft Hushpuppy goes on a final journey to find Marietta, she and the other Bathtub orphans end up at what Zeitlin calls the “heaven of mothers,” that announces itself with a clever sign: the Elysian Fields Floating Catfish Shack LIVE NUDE GIRLS. The whores enfold the orphans in their arms, and together they sway to the music, a fleeting scene of purity and ugly beauty. Hushpuppy is strong, but she’s also just a child, longing to be held.

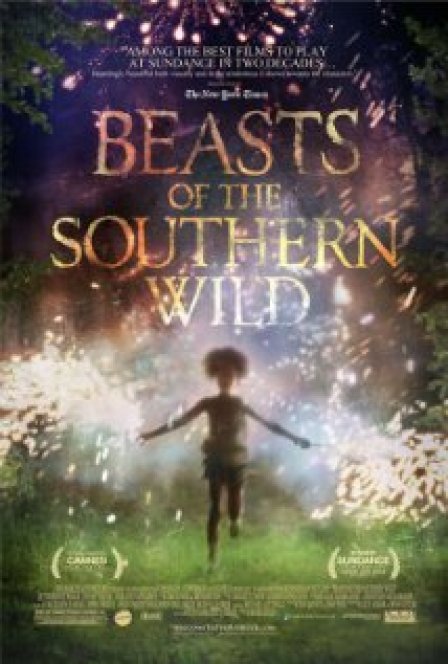

Beasts of the Southern Wild tore onto the scene at Sundance, where it won the grand jury prize, and rapturous critics called it “among the best films to play at the festival in two decades.” At Cannes it was lauded with an extended standing ovation and won the Camera d’Or. Its genesis? Gleaned from their (oddly primitive, 90s-styled) website, Court 13 calls themselves “a grassroots, independent filmmaking army” that considers the DIY ethos a “spiritual requirement.” Zeitlin, presumably the captain of this particular ship, is from Sunnyside, Queens, the son of two folklorists. He met his film compadres at Wesleyan (including Ray Tintori, whose short film Death to the Tin Man won a Sundance award a few years back). They seemed to have decamped en masse to New Orleans, where they made another short, Glory At Sea, a festival hit that set up the magical realist stylings that define Beasts. Still, Zeitlin is quoted as saying that Court 13 is “more of an idea than an organization,” and I can’t help but wonder how the “idea” will survive as the stakes rise. And rise they will, because Beasts of the Southern Wild is a game changer. To anyone who questions the future of American independent film, this is your operatic answer.