[WARNING: This review contains spoilers for The New Testament]

One aspect that tends to be overlooked in most retellings of Christ’s crucifixion is that he knew he it was going to happen. Before the betrayal in the garden, Christ had known for a long time that he was slated for torture and execution. The more interesting adaptations of the story — The Last Temptation of Christ and

Father James (Brendan Gleeson), the head priest of a small Irish town, is listening to confessions when one of his parishioners threatens to kill him on the next Sunday. As a child, parishioner was raped by a priest, but he thinks it’s a more fitting vengeance to kill a good priest like James than another wicked one like his abuser. Over the course of the next week, James interacts with the various members of his flock, none who seem to have any time for him or his religion. There’s the pompous rich misanthrope (Dylan Moran) who constantly ridicules the priest while he himself is awash in complete apathy. There’s an adulterous love triangle of a husband and a wife (Chris O’Dowd and Orla O’Rourke) and a mechanic (Isaach De Bankolé), in which the parties are all pretty much okay with it, but occasionally hit each other, too. There’s an elderly American novelist (M. Emmet Walsh) who wishes to go out on his own terms through suicide, instead of with a lot of pain and confusion. At least the atheist doctor (Aidan Gillen) is open about his disdain for James’s religion, unlike the rest who go through the motions of taking the sacrament and sitting in the pews every Sunday. Lastly there’s James’s daughter, Fiona (Kelly Reilly), from before he took his vows, who shows up back in town after a failed suicide attempt. With a town that is utterly uninterested in the church, seemingly going only out of tradition, what role does James play? Would they even notice if he were to die or, better yet, just skip town?

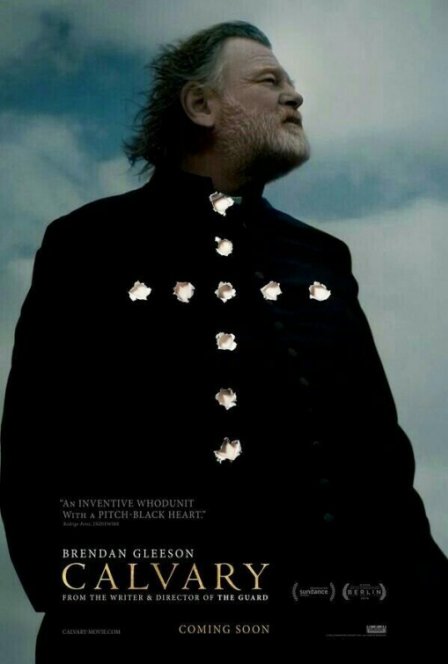

McDonagh’s second film in his recently announced “Suicide Trilogy”, Calvary is decidedly darker than the first installment, The Guard (TMT Review). Quite literally, in fact, as most scenes are shot with overcast skies or in other poorly lit spaces. There are still moments of black humor, particularly when James squares off with his nebbishy fellow priest (David Wilmot), but they are infrequent compared to the heavier subjects McDonagh pursues. James walks among his flock only to be constantly derided and reminded of all of the shortcomings in the church’s messy history. He drapes himself in the traditional cassock, long out of vogue for priests, as if suiting up in armor to go out among his fellow villagers; but where he draws strength from his faith, they see only weakness. Gleeson delivers a powerful performance as James, a complicated and deep character full of kindness, rage, faith, and depression. A big bear of a man, he projects strength but just as easily reveals how vulnerable he truly is by his facial expression when examining the wounds on his daughter’s wrist. Reilly also shines as another lost soul, feeling passed over for an unseen deity in the wake of her mother’s death. She’s strong and witty, but mirrors Gleeson’s ability to intimate that she is also clearly grappling with despair that threatens to swallow her whole.

A film about a priest called Calvary (the anglicized version of the name of hill on which Christ was crucified) clearly has a lot to do with Christianity, and McDonagh doesn’t hide the inherent Christian allegories in the work. It’s not heavy handed or awkward, but is nonetheless prominent in many of the scenes. Still, McDonagh and his talented cast make it interesting by confronting the duality of religion in an honest way that seems more interesting in the pondering than in delivering any predetermined thesis. The church’s crimes are laid out (multiple times) by almost all members of the cast, a community that believes the institution has outlived its usefulness. It’s a pragmatic, if pessimistic, group who see only suffering and cold indifference when they look for signs of God’s grace. But the film isn’t simplistically cynical, also showing the comfort that faith can provide and the ways it can inspire others to act better. James himself comes off like the best model of a priest — he doesn’t care for the petty sins of cursing, or adultery, or even suicide (he helps the elderly novelist procure a gun to euthanize himself and tries to avoid discussing the mortal sin aspects of his daughter’s suicide attempt), but instead simply wants people to care again. But at the same time, he never notices how abandoned his daughter feels when he took his vows, and he’s prone to getting violently drunk, proving the fallibility inherent in delivering God’s message through mortal men.

Kierkegaard once wrote, “I can swim in existence, but for this mystical soaring I am too heavy.” He was saying that even though he knows how to be truly devout Christian, he also knows he’s incapable of achieving those heights due to his own weaknesses. In Calvary, James clearly wishes to soar mystically and inspire his town with great acts. The problem is that none of them would notice his flight, their eyes downcast as they simply try to get through their gray days of various capitulations. He wants to do Good (capital “G”), whether through martyrdom or convincing his would-be assassin to abandon his plans. But would anyone even care? Would it just become another accepted tragedy and people would move on? Christ at least had the benefit of foresight and assurances that his sacrifice was for something; all James has is a pub filled with people snickering behind his back. It’s a powerful portrait of a well-drawn character that comes from the excellent collaboration between McDonagh and Gleeson. James tells his daughter, “I think there’s too much talk about sins, to be honest. Not enough talk about virtues… I think forgiveness has been highly underrated.” There’s strength to be found in faith, but there’s dread and doubt there as well. Calvary examines this double-edged sword and suggests that in order to dispel all of our anger — at each other, at the world, at God — we have to forgive each other and ourselves.