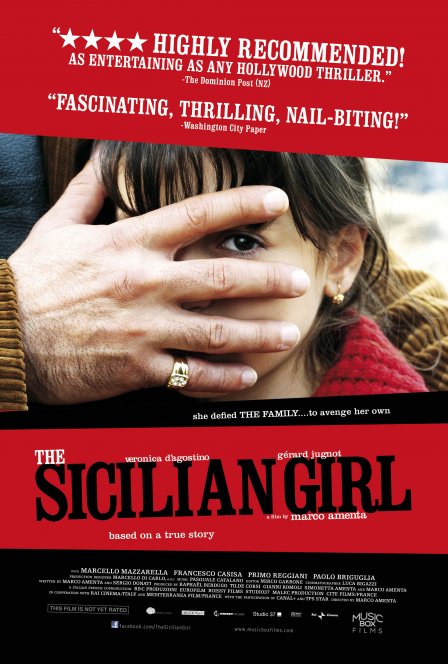

A young, 17-year-old woman turns her back on what is left of her family and the town in which she grew up. Yes, it’s a familiar storyline, but The Sicilian Girl is in fact the true story of Rita Atria (Veronica D’Agostino), who, after the execution of her father by the mafia when she was young, set out to document the criminal brotherhood around her small town of Sicily. A decade later, when her brother is killed and a hit is put out on her, she decides to give all the evidence that she has — diaries, photographs, etc. — to the police, the first time any woman had broken the Omerta (the code of silence) in the Sicilian mafia.

The source material for The Sicilian Girl is fascinating, giving the film all of its momentum. It attempts to downplay the inherent allure and sexiness of the mafia, of the life of power and crime. The mafia here is a dark place, and everyone but the syndicate boss, Don Salvo (Mario Pupella), comes across as a normal person, flawed and trapped in a world where the mafia seems to be their only answer. Rita’s back-stabbing boyfriend Vito (Francesco Casisa) is a prime example of what director Marco Amenta has done right: he’s a normal young man, nothing glossy or desirable about him, yet we see the mob lifestyle turn him against Rita in favor of upward mobility within Salvo’s inner circle. He goes so far as to report Rita to Salvo for visiting the police, having been assigned to silence her the “good way or the bad way.” Vito accepts, but tells Rita to flee Sicily.

Yet it is not the outcome of this historic mob takedown that takes center stage here; it’s Rita’s personal torment. Amenta focuses on the difficulty that Rita faced, the ways in which she was betrayed by those who professed to love her, and the immense danger that was present for everyone who aided and protected her. But the segregation from family and society is never really fascinating or moving. This is unfortunate, because the real Rita is fascinating, and her story is moving. This superficial approach plagues many of the secondary characters: Vito, Rita’s mother (Lucia Sardo), and Paolo Borsellino (Gérard Jugnot), the anti-mafia prosecutor — they are all complicated, tormented characters who are never fully actualized.

D’Agostino, in particular, is leaden. She shines in the subdued, brooding moments of the film — and there are plenty — but her lack of emotional depth is clearly evident. The melodrama of the film works to its own disadvantage: it chooses not to skirt the emotional peaks and valleys of these characters, but to broadcast them, even going so far as to include five-second cutaways of Rita crying on the floor to indicate emotional status. Little is left to the imagination, and the performances leave something to be desired. No one but Jugnot — who is fantastic — can hold their weight in such heavy material.

The half-hearted stylization of the film — especially in the first act — is overwrought in an attempt to capture the idyllic beauty of youth, of Rita’s innocence. The frame is filled with washed-out landscapes and gray skies, but every shot attempts to become a lush portrait or a short symphony of camera movement. In these moments, the cinematography — shot by Luco Bigazzi (Kiarostami’s Certified Copy) — never becomes fused to the story; it pulls the mise-en-scene away from what matters and sets it aside, drawing attention to itself as stylization for the sake of stylization. But this material deserves better. The Sicilian Girl, while engaging, feels like a vehicle with all its tires moving in separate directions. While it’s by no means terrible, the separate facets of the film unfortunately never converge or become something greater than the sum of their parts.