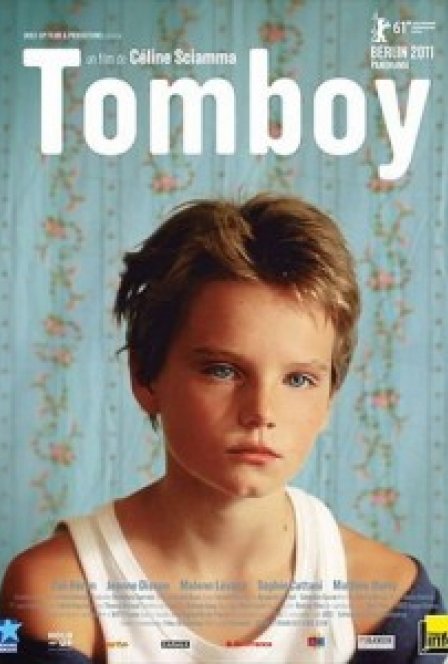

Céline Sciamma had already shown great talent with her 2007 directorial debut, Water Lilies, and after four years, Tomboy delves into similar terrain: the coming of age and blooming sexuality of young women. Whereas Water Lilies focused on the lives of teenage girls, this time around she introduces us to the 10-year-old Laure, who, with her crop haircut and grey sleeveless shirt, could easily pass as a boy in most contexts. Along with her parents and six-year-old sister, Laure (Zoé Héran) moves into a new apartment. Without yet having any friends in the neighborhood, she runs into Lisa (Jeanne Disson), who understandably mistakes her for a boy. Laure sees this as an opportunity and decides to go along with the lie, introducing herself as Mikail, and thus the stage is set for this coming-of-age drama.

Cinematographer Crystel Fournier, who worked alongside Sciamma in Water Lilies, plays an important role in Tomboy. When we see Laure at home, Fournier presents us with a high-contrast, warmly-dimmed light and a camera that often keeps its distance so as to display the intimate family moments from afar. It’s a cozy environment, and Laure certainly has a healthy and loving relationship with both her parents (even if her mother does sometimes hint that she should be more feminine) and especially her little sister (with an impressive and adorable performance by Malonn Lévana). However, as warm and safe as the photography portrays the environment, something is missing for Laure to feel truly at ease with herself. These moments arrive when she is Mikael, the new boy in town playing football outdoors and swimming in a lake with his newfound friends. For these scenes, despite the broadness of the exterior fields and lakes, the camera tends to focus on the expressions and faces of the kids, particularly that of Mikael. And indeed, Tomboy would not have a fraction of its power if it weren’t for Zoé Héran’s outstanding performance as Laure/Mikael and her ability to communicate so much through facial expressions.

Although it would be easy to place Tomboy in the realm of the gay interest film, the label carries too many limitations to really work. While I’d much rather draw similarities to Claire Simon’s 1998 French documentary Recreations, a film that deals with the sociability of children during school playground activities in a cinema vérité aesthetic, Tomboy is more likely to be compared to the well-known Hollywood production Boys Don’t Cry. But Tomboy manages to both limit (by a portrait of Laure) and widen (by posing subtle questions about how we understand sexuality) its subject matter in a way that the overtly didactic American production fails to do so. This is not merely a story about intolerance, and there are no one-sided characters or simple dualisms. Laure’s world is a loving and caring one, yet it’s still terribly difficult for a girl who wants nothing more than to be Mikail.

Even though this is only her second film, Sciamma expertly manages to bring complex political undertones through the cute storyline and a subtle, naturalistic aesthetic that doesn’t rely too heavily on drama or tragedy. One particular scene stands out in that aspect, running the risk of having its powerful symbolism overshadowed by what could become an unnecessary controversial debate. When we get to see Laure stand up from her bath, a full frontal nudity shot reveals to us the “proof” that she is a girl. This is an important scene in the film, for at no moment can we ever see Laure as anything else than Mikael. We know her lie will have to end at some point, but we dread when that moment will come. Mikael is such a lovely and identifiable character, we can’t help but fall in love with him and share his frustration and anguish in that the only reason “she” can’t be a boy is due to the simple (yet culturally prevalent) fact that she doesn’t have a penis.

While some critics have pointed out Laure’s confusion regarding her gender, I instead see the early stages of simply coming to terms with who you are — something that becomes clearer to the audience when Laure tosses away her dress in the middle of the woods. If anyone is confused — and this is another subtlety of Sciamma’s marvelous awareness at dealing with pre-adolescent life — it would be the love interest of Mikael, the typically girlish Lisa. Lisa develops a crush for Mikael after realizing — and verbalizing — that he is somehow different than the other boys. When Lisa is confronted with the truth, it’s hard to tell if her character is slowly coming to terms with her own emerging homosexuality or if she is beginning to understand the complexity of a world far too simplified by gender dualism.

In the end, Sciamma has delivered a straightforward yet deeply perceptive story about the desire to be someone else. It’s as much about the hardships that arise from our imperfect sexual and gender boundaries as it is about discovering first love and remembering those nostalgic days of childhood summer fun (as we get older, we tend to forget how difficult it can be to live in the harsh social environment of children). In a year where dinosaurs have acted alongside Brad Pitt to tell us the meaning of life, where the megalomaniac Lars von Trier has ended the world in order to communicate his depression to the audience, it’s refreshing to see such a sincere, well-acted, and tightly written film presented with such rare sensibility. Tomboy is not only cinematic storytelling at its finest; it’s also one of the most compelling films of the year.