1. River Gods

I do not know much about gods; but I think that the river

Is a strong brown god - sullen, untamed and intractable,

Patient to some degree, at first recognised as a frontier;

Useful, untrustworthy, as a conveyor of commerce;

Then only a problem confronting the builder of bridges.

The problem once solved, the brown god is almost forgotten

By the dwellers in cities - ever, however, implacable.

Keeping his seasons, and rages, destroyer, reminder

Of what men choose to forget. Unhonoured, unpropitiated

By worshippers of the machine, but waiting, watching and waiting

– T.S. Eliot, “The Dry Salvages,” from Four Quartets

All day down at him, there

In the coldest abyss I heard

The stripling moan for liberation,

In floundering rage accuse earth,

His mother, and the thunderer who

Begot him, and they heard him also,

His parents, pitying, yet

Mortals fled the place, for it was terrible,

With him in his chained dark torsions,

The frenzy of the demigod

– Friedrich Hölderlin, “The Rhine,” from The Hymns (tr. Christopher Middleton)

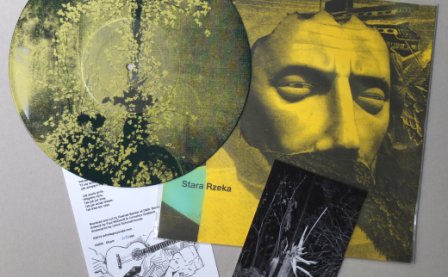

2. Magical Brutalism

In one of his least philosophically justifiable but most profound moments, Schopenhauer claims that music, unlike all other arts, is not mere representation of an inaccessible reality, but a direct manifestation of the will itself (will being the undifferentiable real that dwells beyond human sense perception and cognition). In other words, music was for him the most real of the arts, disclosing the secret form of the world beneath our projections. Music is physis, nature in itself. Likewise, Kuba Ziolek, mastermind of Stara Rzeka, states that the very essence of music belongs to the essence of the river. The stated intent of Stara Rzeka is to incorporate the human as a non-invasive element in the silence and expanse of nature. This intention unfolds into a metaphysical system Ziolek calls Magical Brutalism. Although his manifesto is in Polish, a rough translation provides some clarity: Magical Brutalism is a form of radical materialism that involves the contemplation of human within the raw essence of matter, and an investigation and manipulation of matter’s sacred emptiness. Zamknęły się oczy ziemi, the final statement of Stara Rzeka, represents the culmination of these principles in musical form: the interweaving of song and cosmic noise into a single fabric, the investiture of the human into the sublime chaos of being.

3. The Human

In an insulated house while a haze of media whirls about my sense-organs, I sit to write this review about an album about the wilderness. The television is on in another room. PDFs of Schoopenhauer’s The World as Will and Representation and Hölderlin’s Hymns sit in the system tray next to a comic book reader; of the 15 tabs open on my browser, three are Google Translate tabs of Kuba Ziolek’s writings, and one is open to his Facebook page, where his manifesto appears. I basically understand what he means in spite of the poor translation and the manifesto’s facile interactions with Being and Time and the Kabbalah, but I find it strange to be thinking it where I am. On my second monitor (which I found thrown away on the street), a wallpaper of a lush, mossy pine forest tries to invite me down a single-point perspective path. I can’t go. It’s just a picture, a picture of a sense-representation of a forest, which is an amalgam of billions of organisms and who knows how many bits of organic material that all happened to arise together in a certain region of the map. I’m not even sure where this forest is. For all I know, it’s not some gorgeous, Tarkovskian Zone long beyond the edge of civilization, but the undeveloped edge of an industrial park; and at the end of that vanishing point, I would reach a parking lot and not a sublime river that flows with all the force of time itself.

But I did go outside, and with headphones on, I could almost forget that the woods I walked within were not the Polish wilderness but a small parcel on the edge of a sports complex (complete with screaming children); the woods just barely slipped out of the noose of development because too many mountain bikers complained (there are no mountains in the area). Was this copse a holy site, too? Could the music that filled my ears, a masterful blend of German kosmische, noise, and psychedelic folk (with tinges of black metal), render the matter that surrounded me in a new light, transforming my walk into a glimpse of the sacred? Truthfully, it can, though that process has little to do with the words that surround the work and much more to do with the way in which Zamknęły się oczy ziemi blurs the boundaries between the many cosmoses we as humans inhabit. In order to reveal the artificiality of the boundaries between these spaces, Ziolek leads the microcosmic human to enter into and realize the macrocosmic space, along paths of tradition, continuity, and repetition. Finally, these intersecting paths pour the song into representations of chaos itself, inviting the listener to follow. I stepped forward, I reached out, I touched the earth; and the whole threat of the world’s violence against this clod of turf seemed to surround me. But I could only sense the magic through the membrane of my thrownness: my struggle to sense the sacred seemed to echo the forest’s resistance to its parceling into an order of potential timber and untapped space, ready for use. My experience of that forest did not rise to exalted peaks of splendor; it invested me in what that place really is: a system of material and life struggling to process sunlight in the midst of its status as a natural resource, ripe for its destruction.

4. What Is a Song?

Although Ziolek has claimed that he doesn’t classify Stara Rzeka as a folk project, the melodic structures of Zamknęły się oczy ziemi’s acoustic guitar pieces such as “Melodia,” “Mapa,” and “Mitylena” clearly partake of the styles of psychedelic folksong, a tradition that transcends national boundaries but is nonetheless a tradition, a river whose many tributaries draw the global landscape of folk music into its body. The song-form, in a basic sense, consists in a lyric and melody, usually accompanied by one or more instruments. However, the song is a form that transcends any technical definition. If we are to believe Schopenhauer’s metaphysics for music (or at least, for poetry), song must access something primal within us. The song, then, would be that which is essential to the experience of the human, the direct manifestation of the will as it works through the human self. Psychedelic folk represents an attempt to free song from the static forms of tradition and access deepest within us, a transcendental self, the primordial will that links us back to the unity of the physis.

And yet song differentiates us from that quintessential humanity. The voice of the vocalist is irreducibly singular, so much so that many folk artists are known primarily for their voices or their guitar styles. The I’s and you’s of their lyrics refer to specific individuals; the stories that songs tell involve characters that are not us. But if song didn’t somehow disclose a universally sensible real, it would be utterly inaccessible to anyone but the writer. Looking at the vast swath of vocal music in mass culture, at the overwhelming desire to canonize songs within the halls of hierarchy, it’s clear that this disclosure must be occurring. At that layer, the lyrics either press us deeper into the gate or cease to matter entirely. Ziolek’s Polish lyrics and even his English ones all seem to melt into the cyclic guitar and ambience. At its most powerful, song reaches deep within the existential solitude of the human frame and extracts something whole, complete: a window into our most essential reality, a portal into the raw current of the undifferentiated self. The song is a river of our presence, emptying into the ocean of the real.

5. Beyond

Better histories of the German post-krautrock synth music aesthetic known as kosmische are out there, but it’s important to note that a primary influence of the aesthetic was free-jazz in its cosmic, form-destroying mode (Albert Ayler and Pharaoh Sanders even appear in sample form on Zamknęły się oczy ziemi, showcasing two of the finest workers of raw potentiality in jazz). Kosmische’s attack on the stasis of rock music was two-fold, mirroring cosmic jazz’s assault on form and musicality: it transcended the calcified song-form of rock with lengthy, continuous compositions and used previously unavailable synthesis techniques to evoke the otherworldly. In this way, both free-jazz and kosmische sought to reveal the cosmic, not just in the sense of space, but in the sense of the ordered whole of all existence. Perhaps more strongly tied to this tradition than any other, the music of Stara Rzeka in passages also seeks this cosmic otherness, the vastness of existence, but not in order to evoke its distance from the human. Its macro-cosmos is that of the primordial wild that lies open and available to human ingress. It’s not mere human access to this cosmic rawness that despoils it; it’s certain human relationships with nature that ignore its potential as a source of cosmic connection. Zamknęły się oczy ziemi doesn’t fetishize nature so much as lets it be what it already is; the kosmische-inspired passages of “Czarna Woda,” “BHMTH (czyli historia z wujkiem Albertem),” and “Stara Rzeka,” among others, invite Ziolek’s songs to take up residence in their continuity, blurring the borders between the internal song-cosmos and the external cosmos of the ambient world beyond it. It’s precisely this motion that allows the album to work. More so than 2013’s Cień chmury nad ukrytym polem, Zamknęły się oczy ziemi unites its disparate elements in ways that feel authentic and unfragmented. Its dark passages tinged with black metal don’t so much attempt to artificially insert the genre as logically pass into its territory, one that shares a surprising amount with kosmische and folk song. It too seeks raw essence, but it seeks it in the void of chaos, the sheer abyss that surrounds human solitude. Ziolek doesn’t hide from the dark, destructive elements of reality even as he seeks the beautiful: the sublime yields vast potential to shatter the frozen forms of being, to cast them into chaos.

6. The Sublime Chaos of Being

The real audible form of the cosmos is noise. That’s not to say that it is purely random. There are patterns within it, and to a certain extent, it can receive order. But that ordering is doomed to entropic decay. Nature, physis, is a chaos that ultimately flees all language. That’s why music is most suited to it and why Schopenhauer was so drawn to music: it is capable of communicating experience past language or form. Music, indeed, is like a river, carving out unpredictable coastlines, flowing with vast currents of will. Poets have succeeded at evoking the sublime, but they can only circumscribe the chaos of the river (though it’s precisely this circumscription that consists in its power; poetry is a bridge). Music can partake of it directly, and noise is a particularly sublime example of the purity of reality that it can uncover. The compositions of Zamknęły się oczy ziemi constantly threaten to fall headlong into an abyss of noise, which remains churning like an undercurrent beneath the long-form compositions that feature on this album. But out of these canyons emerges a sound: a guitar, clean, played by human hands. These moments, the interplay between overlapping cosmoses of song, space music, and noise, are the key element of Stara Rzeka’s method. They are the magic unveiling the brutal real.

7. “Mitylena”

I don’t know for whom Ziolek wrote the final song or whether it’s about her. It’s a twinkling, sub three-minute guitar song that seems to fade out before it’s finished. It’s barely produced, and there are no lyrics. You can hear Ziolek’s hands sliding across the strings. I don’t know why Zamknęły się oczy ziemi is the last recording of Stara Rzeka (though he still intends to perform live); perhaps Ziolek felt that this was the most complete statement of his metaphysical project that he could conceive, and that his leaving behind the project only deepens the opportunity to uncover the treasure buried in the depths of Zamknęły się oczy ziemi’s riverbed. That’s not hard to believe, in one sense, because as the last notes of “Mitylena” fade, a sense of finality, not exhaustion, washes over the listener. The album is over, but in the silence that follows, there is no sense of finitude. The Old River still flows on, beyond, and we only have this: an album that challenges its listeners at every turn to involve ourselves in the infinite. But we are always called back, and we almost always go, and what is left at the end of the work is the fading song of experience, the cyclical tune of memory, always carrying us back to the beginning of the melody…

More about: Kuba Ziolek, Stara Rzeka