100 Flowers is a roots-level view of the of the contemporary Chinese musical underground. The aim of this column is to articulate the contingencies of the Chinese scene and arrive at a parallax view of Chinese society from the perspective of its most peripheral negotiators. Read the previous entry here, and email the author here.

“To speak of ‘experimentation’ in China means to discuss it literally: Every single person in the entire country experiments daily and tries out new things. This is particularly true of the last decade. In pre-Olympic Beijing any street, building, restaurant, store, company or regulation could be transformed or even disappear at any given moment. The Nike advertising slogan ‘Everything Is Possible’ reflects the spirit of these times.”

So writes Yan Jun, the de facto godfather of Chinese experimental music. In Beijing, he is often referred to honorifically as Yan Laoban or Yan Laoshi: boss, teacher. This quote is from the insert of milestone 2008 4CD comp Anthology of Chinese Experimental Music 1992-2008, released on Sub Rosa in the same year Beijing hosted the Olympic games and symbolically stepped up to prime position on the international stage. After detailing the strange genesis of the Chinese musical avant-garde via randomly imported Western influences, naive experimentation, and the kind of outsider art practice that could only develop within the context of China’s historic authoritarian rigidity suddenly ceding to a new era of capitalistic flexibility, Yan concludes: “Westerners deconstruct their own traditions in order to redefine them, whereas the Chinese simultaneously attempt to understand the Western tradition and to rediscover their own. While Westerners believe that the Chinese are re-inventing sounds that already exist, the Chinese believe that they are simply re-inventing themselves.”

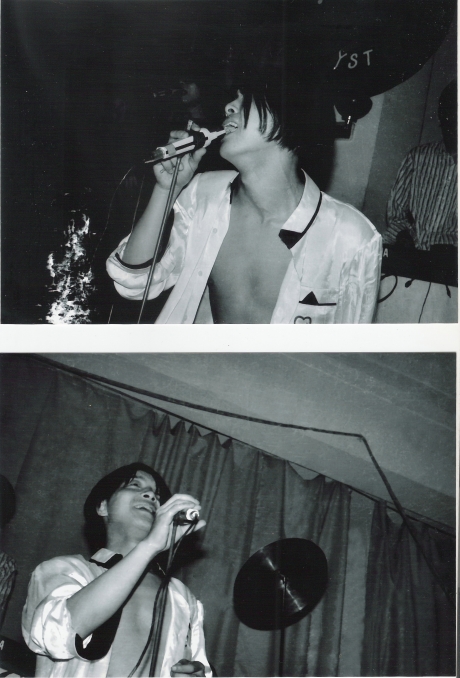

Yan Jun grabbing the mic at a Lanzhou dancehall

Yan grew up in Lanzhou, capital of China’s northwestern Gansu Province. As a college student there in the early 1990s, he was among the first generation of youth poised to seize upon China’s new attitude of economic openness, best encapsulated by then-regnant Deng Xiaoping’s apocryphal edict: “To get rich is glorious.” While his classmates scrambled to heed these words, Yan followed a natural predilection toward more strange and perverse cultural forms, which at the time took extreme dedication to find. He bonded with his mother’s colleague’s son over a shared interest in Beijing metal bands Black Panther and Tang Dynasty, who by then had broken through to become among the first Chinese rock bands to achieve national exposure. From this connection, he met students in his university’s music department who spent their evenings playing in metal cover bands at local dancehalls with 2元(~$0.30) covers.

Yan initially engaged with music via his first passion: writing. An aspiring poet and student of literature, Yan treated his first months in Lanzhou’s underground music scene as an assignment: “I decided to write a report. I spent one month to meet them, to meet all these new kinds of human beings. All this underground life. The music was very poor. The scene… most of them just copied Cui Jian and Black Panther.” He quickly developed a rough classification scheme grading the quality of various Lanzhou bands. At the top was Decay (残响), a Tang Dynasty cover band who won respect for their serviceable renditions of the latter’s hyper-technical, pentatonic riffs. Decay became Yan’s best friends, along with fellow show-goer and Lanzhou’s resident avant-garde music pioneer, Wang Fan.

Wang Fan’s first public performance, alongside his job as a dancehall singer, March 1993

Yan published his first “report” in the Lanzhou Radio/TV Newspaper — a local rag printing showtime schedules — in 1993. After that, he fielded offers for freelance jobs reviewing rock albums, but given his non-linear thinking and the growing importance of underground music in his daily life, these “reviews,” more often than not, took the form of romantic poems. By the mid-1990s, the standard bearer of Chinese music journalism was the Beijing publication Music Life (音乐生活), which focused on “new music.” (This catch-all term included jazz, electronic music, and other Western forms, but was mainly employed because the government forbade any publication explicitly focused on rock ‘n’ roll.) Yan avidly followed the work of Music Life staffer Hao Fang, the first Chinese journalist to write seriously about techno and noise music and the first to introduce Nirvana to the Chinese scene on a wide scale via his 1997 biography of Kurt Cobain. Inspired by the idea that he could write about anything, Yan submitted a 16-page article to Music Life with the hope it would be read by an ex-girlfriend, who had moved to Beijing, and his hometown friend Wang Fan, whom by 1996 had begun home recording with prepared guitars, household objects, and found television sounds, and whom also had relocated to the capital.