Moving Inward: Kwanyin, Olympics, The Tourist Culture

As the halcyon days of Beijing underground rock came to an end, Yan moved inward. “There will be more small concerts, more experimental activities, more strange musicians,” he wrote at the time. He developed a solo music career, producing no-input mixer and feedback noise alongside his evolving poetry and performance art practice. In the wake of the SARS scare, Yan hung out and frequently collaborated with hometown friend Wang Fan, Beijing-born video artist Wu Quan and Zhang Jian and Christiaan Virant of the ambient electronic duo FM3, who would gain international fame after inventing the Buddha Machine years later. This crew played around with event formats, seeking more intimate, casual, and non-rock contexts for their performances, such as a “10 Night Talk” series of discussions convened at each other’s apartments and a 24-hour show in Beijing’s 798 contemporary art district. In 2004, they launched Kwanyin Records, an imprint of Subjam focused exclusively on avant-garde, electronic, noise, and free-improv music.

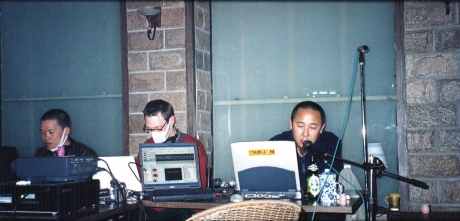

Zhang Jian (left), Christiaan Virant (middle), Yan Jun (right), and Wu Quan (not pictured) perform at Wansheng Bookstore, Beijing, April 8, 2003, days after the Beijing government officially acknowledges the SARS epidemic

In 2004, the Kwanyin scene went international. FM3 began playing isolated gigs in Europe in 2002 and returned in June 2004 for a three-date gig at the Louvre that financed a six-month European tour. Yan and Wu Quan took the opportunity to meet them in Belgium that October, their trip coinciding with a European tour for southern Chinese sound artists Li Jianhong and Wang Changcun. This semi-random overseas meeting of China’s leading avant-garde musicians was fruitful: Wang Changcun landed a contract with Brussels label Sub Rosa, and Yan Jun went home with renewed inspiration to build a culture around the Kwanyin concept.

In May 2005, Yan’s old River Bar associate Gao Feng opened 2Kolegas, a live-music dive bar located on a grassy field next to a massive drive-in movie theater in Beijing’s central business district. Within a month, Yan Jun launched Waterland Kwanyin, a showcase for the city’s weirdest and most extreme musicians — plus plenty of likeminded vagabonds just passing through — that would take place almost every Tuesday night for the next four-and-a-half years. Although 2Kolegas had more of a ‘noisy rock bar’ vibe than the austere, art-oriented venues he had experienced in Europe, Yan immediately seized on the feelings of warm camaraderie these weekly meetings fostered, a throwback to his beloved rock scene of the early 2000s: “When I went to 2Kolegas for the first time, I thought, ‘Wow, it’s another River! I love it!’ I forgot I wanted to find a quiet place.”

early Waterland Kwanyin. left to right: Wang Fan, Zhang Jian, Christiaan Virant, Wu Quan, Yan Jun perform as Spicy Boys

In the early days of Waterland Kwanyin, the core group remained Yan, Wang Fan, Wu Quan, and FM3. FM3’s Zhang Jian had come up playing with some of the earliest Beijing rockers, and his influence brought former Black Panther lead singer Dou Wei, Xie Tian Xiao of the early grunge band Cold Blooded Animal, and even Chinese rock godfather Cui Jian into the mix for improvised, one-off performances. Over the next few years, WK cycled through various trends and influences: Yan recalls that 2006 was dominated by laptop musicians, while 2007 and 2008 saw more activity from the harsh noise collective/label NOJIJI, no wave- and minimalist-influenced guitar music from a group of university bands calling themselves No Beijing, and more traditional-instrument-based improvisation from free-jazz saxophonist Li Tieqiao, zither master Wu Na, multi-instrumentalist Li Daiguo, and inveterate Chinese freak-folk provocateur Xiao He.

Waterland Kwanyin, 2005-2010. top left: Wang Fan; top right: FM3; middle left: Xiao He; middle right: Zhang Jian; bottom left: White (No Beijing); bottom right: H1N1 (Nojiji)

Yan considers early Waterland Kwanyin his “last utopia.” In mid-2007, he began to feel the center shifting once again, the centrifugal force of Beijing spinning out the WK scene as China prepared on a massive scale for the 2008 Summer Olympics. FM3 left for extensive tours of Europe and the US, and Wu Quan limited his involvement in the Kwanyin enterprise. As what Yan now calls “the spirit of pre-Olympic” faded, the audience changed: “Some moved away, changed jobs, moved on. Some just disappeared.” Suddenly, amid a smattering of the few remaining diehards, the audience was rounded out by two sure harbingers of decline: tourists and mainstream media. Although Waterland Kwanyin persisted through January 2010, Yan Jun spent the Olympic lead-up and fallout focusing on his music. “This is the end,” he thought at the time. “Too big, too warm, too open. [I realized] I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life as a party organizer.”

Nevertheless, Yan took the opportunity to organize on a much larger platform, striking a deal with UCCA, China’s foremost contemporary art center, to curate a monthly event series in 2010. This experience crystallized every dissatisfaction Yan had been feeling toward the post-Olympic Beijing cultural milieu in general and the evolution of the city’s underground music scene in particular. “They’re trying to do something very Western, professional, mechanical,” Yan told me in December 2010, days before the final Subjam UCCA gig. “Like I call, we talk, and we decide to do something. But no more support… I like to make something, not just organize something. I want to talk, to think with the organizer, with the venue people. [I like to] spend some time to eat something, drink something, to talk not about the concert, but about everything. You have to waste some time to create.”

posters from Yan Jun’s 2010 Subjam UCCA event series, designed by Ruan Qianrui

At UCCA, Yan Jun continually brushed up against the hyper-capitalist tendencies of Beijing’s contemporary art world. The trend he noticed toward the end of Waterland Kwanyin was much more pronounced at UCCA: “We did have some audience, but 99% were just tourists. This is a time of tourism… You get thousands of pieces of information, invitations, and suggestions, and you pick up everything as ‘I’m interested in this event, I’m interested in this guy,’ but you don’t have time to go to the concert, you don’t have time to listen to this guy. You don’t have any patience to focus on anything. Compared to several years ago, the underground time, it’s like everything you want 10 years ago, now you have it. This is your dream… And now… We’re just tourists from one new phenomenon to another new phenomenon, from one kind of music to another kind of music, from music to exhibition, from exhibition to party, to, you know… We just move, and make a mark on the map, and take a picture, ‘I’m here, bye bye.’ ”

Yan remains one of China’s best-known experimental musicians and organizers, and still hosts international artists attracted by Beijing’s reputation as an emerging frontier for new music. But he has willfully tightened his focus, his network, and his circle. He is currently conducting a “living room tour” of Shanghai, following a similar spate of un-commodifiable private concerts he gave to friends in Beijing last summer. In putting all of his energy into his own art practice — which may be most simply described as a deep meditation on the experience of embodied listening — he is trying to build “something more concrete than a party, something more sustainable.”

“Subjam is a medium,” Yan told me last month, as we shared a cab to meet UK vocal improv master Phil Minton, for whom he had organized a tour of China. Over the course of his long involvement with Chinese underground music — kickstarted by paroxysms of discovery and inspiration, tempered in loud, sweaty bars in the company of his self-selected and self-created communities, and, ultimately, repeatedly impeded by gentrification, globalization, and natural entropic decline — Yan Jun has kept a fire burning in his core. He uses Subjam to share this inner life: “I want to trigger people to a state where they can feel themselves.” In the process of continually re-inventing himself, he has transmuted the Chinese avant-garde from something new to something unique: “Ten years ago, I [thought] new is good, different is good; it is what we are trying to find and trying to create. Now I know ‘new’ is just an illusion. ‘New’ is not my logic, it’s capitalism’s logic. ‘New’ is a lie, actually. It’s not about possibility; it’s just killing the possibility… Real possibility means you have to keep something in the unknown, in the mystery, in the chaos. So now I rethink everything in my mind [from] 15 years ago, 10 years ago, and now I feel very happy… the next step will be more clean.”

“It’s not just, ‘Hey, next Sunday we have a concert, please come with your instrument.’ No. No more. I want to talk with people. ‘Why do we do this?’”