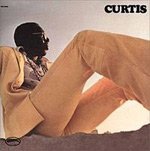

Curtis Mayfield kicked off his debut album, Curtis, with a string of racial epithets aimed dead-on at no one in particular. He had America in his crosshairs. From the crumbling inner-cities to the finely manicured suburbs -- black and white, those both privileged and down on their luck – Mayfield wanted to garner the attention of the masses. And over the 40-odd minutes that followed, he would dissect and explore the deep-seated sentiments of injustice, poverty, and revolution that were afflicting this country in 1970.

The opening track is "(Don't Worry) If There's a Hell Below, We're All Going to Go." It's eight minutes of fire and brimstone -- a pessimistic caveat to a generation left jaded by the failures that followed the promise and ultimate decline of the ’60s, a rallying cry to the ignorant. Mayfield comes out swinging right from the start, bolstered by the absolute might of his backing band. A chugging funk guitar dances with a percussion setup bent on polyrhythm, consistent only in its sporadic deviations. But Curtis ends up digging us out of the dark, psychedelic "Hell" and greets us, rather abruptly, with a swell of heavenly harps on "Other Side of Town," a lonely ballad about the hopelessness that comes with being penniless. Without rushing, he relays the despair of what the poorly informed might refer to as "the underprivileged."

But he reassures us that there's still beauty worth fighting for on tracks like "Makings of You" and "Miss Black America." They soar due to the work of Riley Hampton and Gary Slabo, who share production credits with Mayfield, and can be thanked for the album's abundance of string arrangements. They took Henry Mancini to the streets, mixed in Mayfield's Chicago soul and shook well. Those strings manage to evoke a grab-bag of emotions, from skittering paranoia to absolute bliss, not to mention the eerie calm that can envelop a city in the dead of night. The expert horn section is nothing short of inspired as well, and they're used to their full potential on cuts such as "Wild and Free." Though the harp may seem like Mayfield's ace-in-the-hole, the horns keep the songs on their toes: that brass force continually provides balance to the vocal's slight falsetto, which might come off as wispy if Mayfield weren't so confident.

One could make the argument that Curtis hinges on two tracks. One of them is "Move On Up," the 9-minute expedition that doesn't need an introduction (especially since a certain Mr. West slowed it down to right a few wrongs and help him write some song). The other is "We The People Who Are Darker Than Blue." It's a beautifully structured catharsis, plucked from the bowels of Curtis Mayfield's soul. It starts off slow, with intention, but before long the band drives into a fury of drumming and blasting horns, only to ease back out over a sprinkling harp, as if the digression was just a bad dream. It's a perfect display of the album's duality, as gliding soul meets the hard-hitting funk that would later be refined on the ghetto symphony Superfly.

By all counts, Curtis got the ball rolling for a new type of socially conscious R&B and soul. It took black music beyond Hitsville, USA and gave it a set of principles, which Mayfield had already hinted at in his earlier work with The Impressions. The importance of his message sometimes overshadows the density of the actual music. Curtis is a lush, thick record that not only supports a healthy dose of social commentary, but also embraces the listener in a distinctive, velvety swathe that, until then, was foreign to soul records.