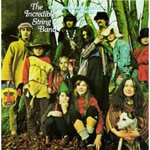

Though they didn’t go over too well with the mudslingers at Woodstock, The Incredible String Band were some of the biggest thrill-seekers in late-1960s psychedelic folk. Judging from the group photo on the cover of their third album, The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter, their lives were just as full of fairy-tale images as their music. In 1968, when The Beatles donned white kaftans and absconded to India to study transcendental meditation, Robin Williamson had already returned from Morocco carrying an oud, a gimbri, a sitar, a water harp, and a bag full of melismatic vocal licks. Though former bandmate Clive Palmer seemed lost to India and Afghanistan forever, Williamson reunited with rock guitarist Mike Heron and set up house in Pembrokeshire, Wales, where the Scottish duo experimented with communal living, ran around wearing Renaissance costumes, and mastered enough non-occidental string instruments to justify their towering moniker.

After their second LP, The 5000 Spirits or the Layers of the Onion, confirmed their movement away from traditional Celtic roots, The Incredible String Band hit upon a distinctive marriage of East and West that would become their signature sound. With The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter, which expanded their lineup to include girlfriends Licorice McKechnie and Rose Simpson, the group pushed the logic of cultural hybridization further than anyone else had dared. Unlike other members of the Sgt. Pepper’s generation, Williamson and Heron were ready to do more than just quote the Middle Eastern and East Asian musical traditions; they allowed these influences to explode the very fabric of their songwriting.

If only for its hallucinogenic quality, listening to The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter is a lot like watching the dream sequence in Walter Lang’s 1939 remake of A Little Princess, where the film suddenly switches from monochrome to Technicolor, sublimating the life of an orphaned Shirley Temple into a tale fit for the Brother’s Grimm. Shirley, now styled as a petticoated princess, arbitrates a dispute between an evil witch (her tight-lipped headmistress) and a lovely shepherdess (her beloved teacher) over a “stolen kiss” as she is regaled by a swirling cavalcade of pied pipers, court jesters, and cooks armed with over-basted suckling pigs. If we can’t triumph the powers that be, the film seems to suggest, why don’t we just drop out of reality for a while and write our own tall tales?

Equally enchanting and enchanted, The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter provides a potent musical antidote to today’s daily grind. Taking off from the group’s farmhouse in Pembrokeshire, Williamson’s soaring tenor catches on a gust of wind and sweeps us into a promised land filled with panpipes and misty garden walls, frankincense and minotaurs, spinning castles and witches wearing black cherries on their fingers. Though each song unfurls like one of those long-winded adventure stories that bards rattled off to the ladies back home, Hangman’s is a movement not only across the seven continents but backwards through time, where childhood make-believe magnifies into courtly love and a stroll down a tree-lined lane becomes a caravan down the Silk Road. In “A Very Cellular Song,” a 13-minute ode to an amoeba that joins a Sikh hymn with a Bahaman spiritual, the group enumerates the joys of “living the timeless life” -- perhaps hitting upon the secret ideal of all true-blue hippies, past and present.

But while The Incredible String Band were busy luxuriating in their own escapist fantasy, they were also working long hours to break apart traditional song structure and confront their glut of exotic instruments with their wickermanian aesthetic. With the advent of 8-track recording, they had finally discovered a way of putting all of their ideas (and all of their instruments) down on tape. And Williamson and Heron were overflowing with ideas -- so much that they didn’t see the point in drawing any one of them out into a verse-chorus-bridge-chorus number.

“I did not write this song,” Williamson sang on their first album. “It was my joys and sorrows that bore it.” Obviously, The Incredible String Band did write their songs, and we cannot overestimate the amount of time it probably took them to sync up each microtonal flutter of Williamson’s voice with a corresponding sitar arabesque. But, listening to Hangman, we cannot avoid the feeling that Williamson and Heron were trying to reverse the equation that had come to dominate even the most “eclectic” music of their time: the channeling of sentiment into form, as opposed to the accommodation of form to sentiment. Though their transitions from raga to music-hall parody were nothing short of virtuosic, The Incredible String Band were less interested in blowing their own pennywhistles than in confronting the fact that no single melody, no single musical language, suffices to capture all the colors in the psychic rainbow.