We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music and films that helped define the year. More from this series

Popular art criticism has responded to these developments, although for the most part lagged years or decades behind. Nowadays, for instance, despite its ubiquity in online criticism, the idea of the “male gaze” is mostly the butt of LOLs from scholars, who see it as heteronormative, technologically determinist, and basically insane (it hinges on dudes feeling castration anxiety from women’s lack of having wangs) — at least as it was originally conceptualized in the 1970s by feminist film scholar Laura Mulvey.

But one area where changes in criticism have sped past changes in art is in figuring out how to monetize free content. While many of us might download Bangerz for free after we also paid nothing for a Jezebel article about why Bangerz is #problematic, only Jezebel makes money off our not paying anything. Of course, as an editor at Tiny Mix Tapes, I realize that ad revenue supports a wide range of online outlets. But unlike the subscription model used by magazines and newspapers, with free online content, we’re just as likely — or maybe even more so — to click on something that seems idiotic, over-the-top, or just plain weird as we are something that seems smart, accurate, and well-written3.

Or: I wouldn’t pay for a subscription to Ron Paul’s newsletters, but I do like to see what’s going on at the Drudge Report every now and then for the lulz. Readers of the right-wing persuasion no doubt click on Daily Kos for the same reason. When it’s free for us to hate-read, not only do we not lose our cash for reading something we disagree with — there’s also little economic motivation to publish anything that isn’t a divisive polemic.

The Big Book of Online OUTRAGE by Rainbow Brown

The Big Book of Online OUTRAGE by Rainbow Brown

What this means for art criticism, on the one hand, is that the most preposterous claims — like that Janice Joplin was racist for singing in a way that sounds like a black person, according to this one dude at The Atlantic — proliferate, in large part thanks to people like me who link to them on my Facebook so that my friends and I can make fun of them.

On the other, it means that websites have more and more economic motivation to actively seek out ostensibly offensive content that most of us would never be exposed to otherwise.

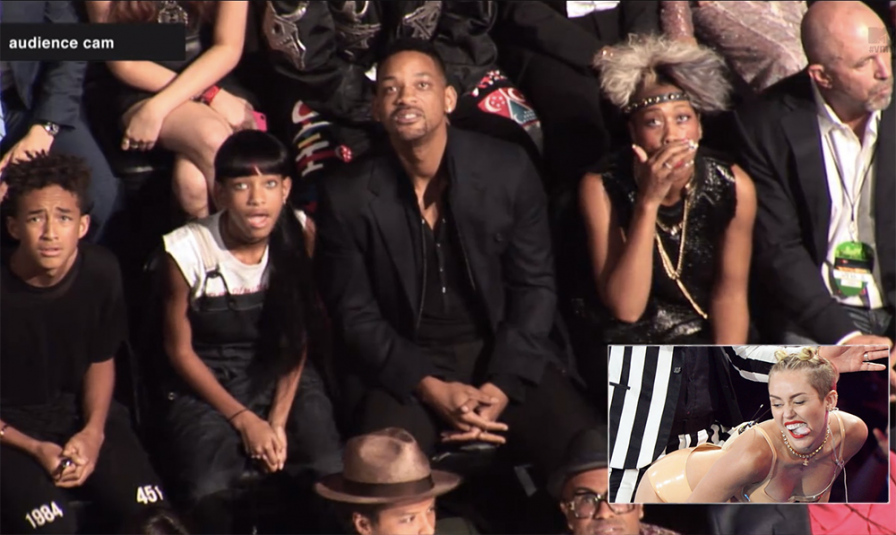

But in doing so, they perpetuate the production of such ostensibly-offensive content: in 2013, websites like Jezebel, Buzzfeed, Flavorwire, Upworthy, and The Atlantic helped Miley Cyrus make enough Benjamins to bankroll a lifetime’s worth of diamond-crusted grills and booty-shaking backup dancers.

Two Communicative Forms, One Cup

This parasitic profiting from and promotion of offensive content is hypocritical, to be sure. But what’s even more convoluted than how the offense industry earns its living are what its criticisms imply about our relationship with art and our beliefs about its influence on society. Clearly, underlying criticisms of Cyrus, Lorde, Thicke, Allen, et al. was the assumption that offensive art is somehow connected to real-life prejudices and inequalities. But the line connecting art and life seemed too blurred to follow.

Do we believe that exposure to offensive art actually breeds prejudice in easily-influenced viewers? If so, wouldn’t The Atlantic and Flavorwire actually have created a bunch of racists by increasing the exposure of Miley Cyrus’s twerking? Put differently: if someone made an unintentionally racist music video and nobody saw it, would it actually harm anyone?4

Sure, anti-Robin Thicke activists banned “Blurred Lines” from their campuses in the UK. But even then, it was unclear if their ban was to keep the song from inspiring hatred and violence — like German and Central European bans on Mein Kampf — or if they were simply making a statement about their own values.

If they were, it came at the expense of art more than of would-be rapists.

While not all offense-based criticism called for censorship of artistic expression, the trend did shackle art’s range of expression. The meaning of “Blurred Lines” is vague at worst, and its critics’ claim that the line “you know you want it” is rapey is bizarre. But debating the lyrics of “Blurred Lines” or the visual semiotics of “We Can’t Stop” is beside the point. Regardless of its textual meaning or lack thereof, by turning the song into a vehicle to support a cause, offense criticism has forever associated “Blurred Lines” with rape for audiences worldwide.

This pattern was replicated everywhere in our discussion of popular art this year. Even if you thought, as I did, that Miley Cyrus’s VMA performance was gloriously weird and refreshingly opaque, our discursive space only allowed two interpretations: it was racist/it wasn’t. As we reduced our discourse about music, TV shows, film, and music videos to lowest-common-denominator ideological critiques about their representations (or lack thereof) of race, gender, and sexuality, we constricted both the communicative and transformative possibilities of art in general. Including its ability to promote social change.

Particularly since art wasn’t even allowed to comment on itself, to chime in on 2013’s representational debates. Lily Allen’s video for “Hard Out Here,” a critique of Miley Cyrus and Robin Thicke specifically, and the music industry in general — which attempted to ironically recontextualize twerking in a parody of Cyrus’s video — was nearly as widely criticized as the original. Reproducing racist imagery even to criticize it, the argument went, was still racist. At least it was in visual and musical culture: the written word seemed curiously exempt.

One critic at The Guardian, Suzanne Moore, wrote about looking at the video, “Maybe I have read it wrong. But what I see is the black female body, anonymous and sexualised, grinding away to make the rent.” Somehow, this columnist saw three of the extremely talented dancers in Allen’s video (there were other dancers who happened not to be black; they escaped her notice) as just black female bodies, generalizable, replaceable, and devoid of agency or individuality5. Allen’s visual critique was clumsy, not offensive; Moore, however, used language to deliberately turn individuals into racialized abstractions.

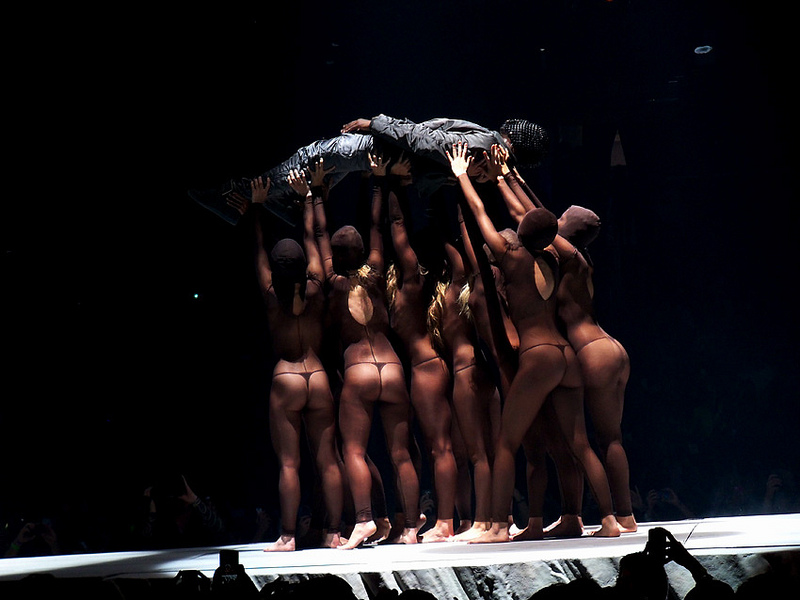

Kanye West + some dancers (photo by U2soul)

Kanye West + some dancers (photo by U2soul)

Lily Allen + some black female bodies, “anonymous and sexualised, grinding away to make the rent”

Lily Allen + some black female bodies, “anonymous and sexualised, grinding away to make the rent”

Throughout 2013, the double standard we allotted the written word allowed multiple similar reductions of individual agency into the neatly textbook categories of identity politics. The man named Terry Richardson, for instance, took all of the blame for the woman Miley Cyrus’s supposedly sexually-exploitative “Wrecking Ball” video, despite it being her own concept. Meanwhile, the man named Robin Thicke took the blame for his supposedly sexually exploitative “Blurred Lines” video, despite it being the concept of the female director Diane Martel.

At the same time that offense criticism furthered the stereotype that women have no sexual or creative agency, it lazily over-employed the concept of “cultural appropriation” to freeze the natural fluidity of culture. This year, offense criticism singlehandedly turned the practice known as “twerking” into a signifier of blackness and stripped the dance of any possibility for cross-cultural (whatever that means) appeal, of any possibility to signify anything besides blackness6.

3. Speaking of free, it’s cool that all these writers took some liberal arts classes in college and now get to spend their time writing unpaid articles that make internet publishing conglomerates buttloads of money.

4. Probably not, but these websites wouldn’t make any money off it, either.

5. The actual individuals those anonymous black female bodies belonged to didn’t take kindly to criticisms of their hard work, and took to Twitter to defend Allen.

6. Yet while a dance move done originally by some black people has become doomed to be eternally read as a stand-in for all black people, traditionally white dance moves escaped becoming racialized.

We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music and films that helped define the year. More from this series