Welcome to Screen Week! Join us as we explore the films, TV shows, and video games that kept us staring at screens. More from this series

Let’s face it — art is escapism. We might feel like we’re doing serious work when we catch up on arthouse films or when we listen to music that preaches values we believe in. But at the end of the day, sitting on the couch is just something we all need sometimes. The old guard has a vested interest in inflating the significance of the media we consume in our spare time, in making us feel as if it’s our collective duty to remain caught up with the season’s latest rehashes on contemporary issues. But is escapism in itself really so shallow? Is it so low to seek visceral immersion in this terrifying and numbing reality we’ve found ourselves in? And more importantly, if we’re going to burn away our hours staring at a screen, why just absorb when we can participate?

Amid another year wherein it seemed as if the amount of music to listen to and TV to watch reached a breaking point, video games pushed forward yet again as one of the defining platforms of our time. After all, we’re talking about a medium that distinguishes itself from other artistic formats in the agency it gives to its recipient, placing the experience of a video game as much in the hands of the player as in the hands of the developer. And never before has there been so much freedom in how we create that experience: Between AAA titles that pushed the boundaries of the open-world concept to unimaginably beautiful new heights (The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild) to indies that sent us tunneling down absurdist rabbit holes (West of Loathing), the games we played in 2017 reflected the expanding chaos of our world, trading in linear pathways for freeform silliness (Super Mario Odyssey) and easy relaxation for carpal tunnel-inducing mindfuckery (Getting Over It With Bennett Foddy). Even if we couldn’t control what was happening beyond our front door, we were the masters of our domain, as far as our living rooms were concerned.

Of course, in the end, it’s all fun and games, and sitting at home isn’t going to fix all of our problems. But rarely have we felt as nourished as we have after picking up one of these 15 gems, each one as inspired and invigorating as any film or album or book from last year. It’s with that in mind that we present our Favorite Video Games of 2017, with a little reminder that if you’re going to escape reality, do it right.

15

Animal Crossing: Pocket Camp

Developer: Nintendo

[iOS, Android]

In 2017, it often felt like our most basic sense of community and fellowship to one another continued to deteriorate. It was a small but powerful relief when Animal Crossing: Pocket Camp hit the app store. Beyond the purely nostalgic appeal of hopping into a camper and getting away from it all, of hearing the sound of leaves crunching underfoot as we ran errands for all our cute animal friends, Pocket Camp distinguished itself with a simple goal for players: give to others, unconditionally, purely for the sake of giving. The fact that the game drew such ridicule for this suggestion of unreturned generosity is telling of our world in and of itself; but even in the face of its haters, Animal Crossing felt like a big bear hug from an old friend, the sort of neighborly, low-stakes game that championed a kind of calm that seems to be disappearing from our lives. Best of all, it was essentially free, with pay options only cropping up if we felt the need to speed up our steady furniture accumulation — as if the game itself was asking us, hey, why are we always in such a rush?

14

Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice

Developer: Ninja Theory

[PlayStation 4, Windows]

Hellblade boasted a range of state-of-the-art technical features, from expressive motion capture to miasmic binaural sound design, but its most effective trick was decidedly old school: a disorienting, medium close third-person point of view. Unlike first-person walking simulators, which often dissolve the nuances of character in service of narrative simplicity and reduce the experiences of being, of embodiment, to mere avatardom, Hellblade never let you forget whose story you literally stand in the shadow of. Considering that one of Hellblade’s core mechanics involved the manipulation of perspective, there was a harmony of theme and structure, a rare achievement, even in consideration of the whole history of the medium. That these devices were utilized in service of a melancholic, Herzogian fever dream of love, loss, trauma, and hereditary psychosis was more astonishing still. As VR tides continued to rise throughout 2017, Hellblade made a convincing argument for the ascendancy of those smaller stories yet untold, over the paradigm-shifting promises of vulpine industrialists. Best of all, Hellblade’s commercial success proved that there’s a market for games as immersive, empathy-building experiences, which is perhaps the most impressive of its tricks and achievements.

13

Puyo Puyo Tetris

Developer: Sonic Team

[Nintendo 3DS, PlayStation 3, PlayStation 4, Xbox One, Nintendo Switch]

I copped Puyo Puyo Tetris on a whim, hoping to eke a few hours of portable puzzle-solving between classes. Turns out, I’d underestimated just how much longevity this title packed within its cartridge: it’s the Switch game I’ve most frequently returned to this year. Whether I’m playing it on a TV at a friend’s get-together, getting decimated while attempting to play competitively online, or just plugging my way through a ridiculously written story mode, I never seem to get bored with its simple and succinct gameplay, which pits two classic stacking puzzles against each other, side by side. Puyo Puyo Tetris was a straightforward title that breathed new life into veteran concepts. The learning curve’s quick, but there are hours and hours worth of strategic depth built into the game’s blocks and blobs.

12

Prey

Developer: Arkane Studios

[PlayStation 4, Windows, Xbox One]

Who would have thought that a first-person, sci-fi horror throwback under the premise of an alternate reality (wherein JFK was never shot and the space race flourished) could be so captivating? Touted as a “space horror version of Groundhog Day” at E3 2016, Prey certainly delivered in story, but it became a true standout through its slick, immersive atmosphere, inspired by films like Moon, Starship Troopers, and The Matrix. It was such a joy to play an original property that recalled playing Doom for the first time, but the game complemented its retro aesthetic with interrogations into morality and artificial intelligence. While Prey is that rare, underrated gem likely to be buried among similar genre titles, it was nonetheless an alternate reality worthy of being lost in.

11

Golf Story

Developer: Sidebar Games

[Nintendo Switch]

Golf Story was one of the biggest surprises on a system that was itself one of 2017’s biggest surprises. The game sported a typical hero story, but twisted such that your golfer was old and unlucky instead of young and plucky. And instead of townspeople cheering you on, the crowd consisted of a crew of sarcastic golfers rooting for your failure, in the most pleasant way possible. The story was amusing, but it never got overly involved, present just enough to introduce new courses and rivals with flair while letting the excellent gameplay speak for itself. Traditionally, sports games don’t have stories, but the bizarre combination offered by Golf Story led to an intriguing mix of genres that was absolutely worth the low $20 entry fee.

10

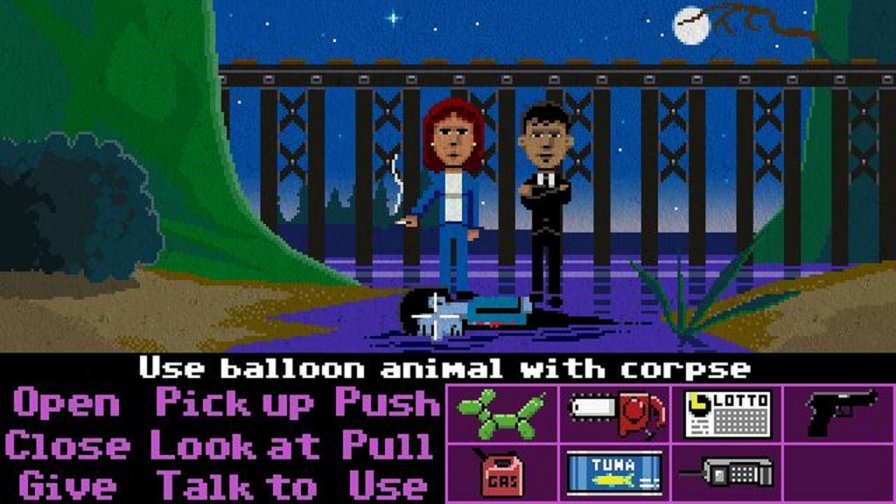

Thimbleweed Park

Developer: Terrible Toybox

[Xbox One, Android, Windows, Nintendo Switch, iOS, Linux, Macintosh OS]

The 1990s were the golden age of the point-and-click adventure game, largely due to companies like LucasArts and Sierra Entertainment. But the genre has persisted over the years and even thrived with the recent popularity of tablet devices. Indie developers of all stripes have embraced these casual (and sometimes frustrating) games, often applying a pixelated aesthetic in homage. Thimbleweed Park, from the creator of Maniac Mansion and Day of the Tentacle, was this year’s standout example. All the aspects of the classic gameplay were there: the crosshair cursor, the blocky verb actions at the bottom, the humorous dialogue, and of course, the bizarre use of objects to advance the story. Thimbleweed Park gave us control over two secret agents plucked right from The X-Files, a female video game programmer, a foul-mouthed clown, and a ghost, all humanized with superb voice acting. And at its core, the game’s logic was pleasantly goofy, much like its predecessors.

09

Getting Over It With Bennett Foddy

Developer: Bennett Foddy

[Windows, Macintosh OS, iOS]

Part B-game, part Sisyphean metaphor, part pop psychology, tough-love therapy, and meme generator, QWOP mastermind Bennett Foddy’s latest absurdist platformer carved out an unexpected niche in the 2017 zeitgeist thanks to the revival of tired conversations about difficulty in games sparked by Cuphead’s punishing, retro-style gameplay. But Foddy’s incredible, impossible, holy mountain-climbing abstraction brought new life to old discourse by challenging the nature of simulated obstacles in gaming, testing the player’s perseverance by delegitimizing itself as just another emblem of gamer credibility, and actively questioning why we’re even playing. Foddy created a game that could’ve used its quick novelty and high meme potential to cash in on a voracious Twitch and YouTube market. But with theming that blends a delightfully clumsy control setup, slapstick physics, and existential horror/psychological torment courtesy of Foddy’s alternatingly abusive and encouraging voice-of-God commentary, the game also proved to be one of the most unique interactive experiences of the year. As for my own quest up the mountain, I still haven’t hit the top, and I honestly probably never will. But I’m fine with that. I think Camus would understand.

08

NieR: Automata

Developer: Square Enix

[PlayStation 4, Windows]

A tree in the vastness of a broken future, its many branches varied and reaching toward an open-ended sky. It’s these visuals in the bleak fast-forward of NieR: Automata that best exhibits how rich and entrenching the storytelling was with the latest in the series. And though the multiple endings and perspectives (and the chase therein) were the top-level canopies of NieR: Automata, it was the interactions and revelations drawn by 2B and 9S that truly stripped you of your own cynical bark. There were plenty of post-apocalyptic games littering the gaming market, each fitted with its own emotional gimmick, yet it was the lack of a gimmick that set NieR: Automata apart. The branches of its storytelling reached into the futuristic ether, a towering coniferous that brightly blossomed the higher you climbed it. Much like that tree, NieR: Automata shouldn’t exist in this prophetic space of humanity’s not-so-distant landing spot — and yet it did. And I’m glad it did.

07

Night In the Woods

Developer: Infinite Fall

[Windows, Macintosh OS, Linux, PlayStation 4]

Here’s an Indie Game Mad Lib: Night In the Woods was a self-aware, slice-of-life adventure game with an ironic sense of humor about millenial social fatigue, set in a 2D cartoon world populated by morose talking animals. The game also mercifully swam against the rushing currents of contemporary gaming culture. While the industry at large continued to thrive on unquestioning nostalgic dogma, Night In the Woods sought out the true value of reminiscence in an era of profound disconnect; while most games took on social issues with a myopic perspective and a heavy hand, Night In the Woods was, if anything, too muted in its depiction of the communication breakdowns plaguing a generation buckling under the weight of modern strains of anxiety, depression, and socioeconomic disenfranchisement. The game was stocked with authentic characters whose stories you learned gradually through awkward encounters and halted conversations, all simultaneously desperate for something meaningful to happen and terrified of making themselves even the slightest bit vulnerable. It was either an empathy machine for a society automating itself into isolation or a quirky little story about how we’re all just confused idiots floating directionless in space. The result was the same.

06

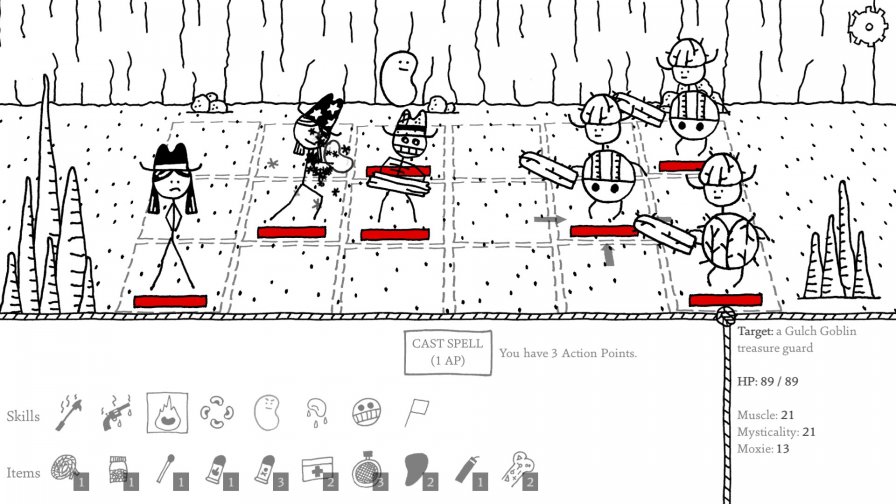

West of Loathing

Developer: Asymmetric

[Windows, Macintosh OS, Linux, iOS]

The Western is America’s answer to European medieval fiction. Both genres are essentially fantasy that romanticize the unwritten reality. Both possess a certain character that reflects ideals for each location. Some would argue they whitewashed the truth, a claim for which there is some validity. However, what truth it hid was more mundane: These times were actually boring. In Europe, knights were spoiled rich boys, marriages were political and financial transactions, and the life most people had was tending to a farm. The American West was not full of gunslingers, cowboys, and prospectors, but immigrant farmers, bored Civil War veterans, and cattle ranchers just getting by. Sometimes it’s important to reflect on the absurdity of these fictions in subtle ways. Meat as a currency. A necromancer raising dead saints and antipopes — taking back their “holy relics” in the process — only for them to be instantly killed by a lady with a bone saw. Crowded trains waiting for the continental railroad to finish. A ghost town’s bureaucracy denying cow-punchers a shot of whiskey. A great cataclysm occurring when The Cows Came Home. It was all so goofy. But when you think about it, aren’t Westerns just as ridiculous?

05

Persona 5

Developer: P Studio

[PlayStation 3, PlayStation 4]

Although its core gameplay wasn’t a revolutionary departure from the JRPG subgenre’s tropes and traditions, Persona 5 kept me coming back to its magical-realist incarnation of Tokyo on aesthetic strength alone. Visually, aurally, and ethically, the game’s cast of delinquent teens had their finger point-blank on the pulse of 2017, bumping future-funk jams in the background as they dealt vigilante justice to their oppressors, all the while decked out in high-fashion fits equally inspired by Victorian literature and late-70s punk. The game oozed style down to its animated menus, bordered by sketchy illustrations: though much of the game took place in a surreal meta-reality populated by demons, an elegant charm stitched the torn fabric between its fantasy and beautifully mundane reality. Give Persona 5 a try for yourself: you’ll exorcise ancient evil, buy soylent from vending machines, date the two-dimensional character of your dreams, and have uninterrupted fun through it all.

04

Horizon Zero Dawn

Developer: Guerrilla Games

[PlayStation 4]

Horizon Zero Dawn might not have offered the best open world of 2017 — hi, Breath of the Wild; hello, Assassin’s Creed Origins — but no matter what it appeared to lack, in the superficial and reductive comparisons that commonly pass for game criticism, it more than compensated for with hope, hard-earned humanism, and technical polish. 2017 being a banner year for the format, there were plenty of games that did more, but few that did better. Whether in terms of the satisfying tactility of its weapons, the impossible, magic-hour glow of every single in-game moment, or the unexpected, hard sci-fi implications at the core of the narrative’s parallel mysteries, Horizon Zero Dawn presented itself with more craft, care, thought, theme, and feeling than any other escapist entertainment this year. Sure, the characters’ photo-realistic wax figure faces could be jarringly unnatural from time to time, but what this game had to say — about faith, our relationships to technology, and the very concept of the uncanny valley — was so much more impressive than any mere graphics engine could ever be. While I came to fight robot dinosaurs, I stayed for the mechanical flowers that pollinate poetry. And during a year that consistently dimmed belief in our collective myths — such as peaceable resolutions to decades of cultural Balkanization or the prospect of a decent, sustainable future for humankind — Horizon Zero Dawn served as a balm, a worry stone, a bright and vital reminder that, no matter what, life rarely fails to find a way.

03

Super Mario Odyssey

Developer: Nintendo

[Nintendo Switch]

All due respect to The Young Bucks, The Usos, and The Beatdown Biddies, but Mario and Cappy were the greatest tag team of 2017. Mario games tend to have a central gameplay conceit, and with its “Mario’s hat is a sentient being now” mechanic, Super Mario Odyssey was no different. In order to save Princess Peach (as well as Cappy’s sister Tiara the tiara) and restore balance to the universe, Mario and Cappy must join forces. With Cappy by his side/on his head, Mario was able to jump higher, accumulate more coins, and of course possess unwitting enemies before using their abilities toward his own purposes. The resulting body horror made for one of the single-best platformer experiences ever, which might be a little hyperbolic, but I mean come on, it’s-a him, Mario! That name carries a lot of prestige with it, and this latest adventure more than lived up to the pedigree. Collect hundreds upon hundreds of Power Moons, wear a variety of fun costumes, take over a human’s free will and force it to drive an RC car around a racetrack in under 30 seconds. Along with another game that shall remain nameless because this blurb isn’t about it, Super Mario Odyssey made the Nintendo Switch a console worth owning.

02

Cuphead

Developer: StudioMDHR

[Xbox One, Windows]

The little Xbox One champion that could this year was also one of 2017’s biggest surprises: a run-and-gun platformer based on rubber hose animation. If you asked if we wanted to play a game that looked like Steamboat Willy, we’d probably be a little reluctant at first, but usually the best and most unique games are the ones you didn’t know you wanted. Cuphead had truly stunning animation that convincingly reimagined what playing a 1930s video game would be like (thanks to independent Canadian studio StudioMDHR). But besides the delightful aesthetic quirk, there was also an impressive difficulty to the game that made it pleasantly addictive rather than annoyingly impossible (see Crash Bandicoot N. Sane Trilogy). So many indie side-scrollers rely on the same tricks from decades before, but Cuphead had mechanics that didn’t allow players to simply remember patterns. In the end, Cuphead was a reminder that all we really want in a game is to have a fun and be challenged.

01

The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild

Developer: Nintendo

[Wii U, Nintendo Switch]

“Games and play are not identical categories. Games are organized forms of play; they have elements that might not be playful. Finite games are games that come to some kind of conclusion, and the conclusion governs how the game is played and what the game means.”

The above quote comes from a book about baseball (Fail Better, by Mark Kingwell). It’s strange to me that, in 2017, I’d be looking to a book about a physical sport for a way to understand a video game, but it’s also not surprising that the lines of philosophy in sport, video games, and art run concurrent (hence why you’re reading a video game feature on a website that focuses on music). It’s often what we do when we try and grasp various forms of art: we end up looking back as well as across to see the permutations of ideas run through their forms and related ideas. Sometimes we look at Cage and say Duchamp, or visa versa, as often it seems as if one is looking back at the other, even though often (almost always) they were both working simultaneously. Shared philosophies are reflected in aesthetic permutations in various mediums, but it’s less interdependent and more of reaching to an idea of why we talk and write about our experience with art.

Forgive the digression, but I personally find this above point important, at least for myself, when I try to understand what I find so enjoyable, invigorating, impactful, and remarkable about Breath of the Wild. In all ways, it shouldn’t be: another franchise game in the running output stream of a mega-sized corporation that specializes in spectacle and entertainment, etc., etc. But against an understandable skepticism against large-scale video game producers (cf. loot boxes, the existence of EA), we often forget companies like Nintendo were at the start of the medium, or in fact were the start. Breath of the Wild was not a swoop-in project from the outside, even if it’s open-world construction bears some resemblance to games like Skyrim or Assassins Creed. BOTW’s true predecessor exists in its own lineage: the original Legend of Zelda.

Before the term “sandbox game” was coined, Shigeru Miyamoto referred to the original Zelda as a “miniature garden that they can put inside their drawer.” I love this quote because it reflects how games at the time were built around experimenting with the experience rather than the presentation of a cinematic, linear plot. Zelda was approached more like a garden than a book. Early games, in their limitation, had to find new ways to approach a person’s interaction with it, and after the limitations of platform games became obvious, why not make a game wherein a person just might miss one of the game’s crucial objects because it’s not explicitly laid out for them to grab? For those who are unfamiliar, the original Zelda puts a sword, your main weapon, in the care of an old man inside a cave. This cave is in the first screen you start on, but nothing stops you from not getting it, save for an extreme difficulty navigating the surrounding areas full of enemies (it is possible to make it all of the way to Ganon, the final boss, without the sword, and to play the rest of the game without it). Everything about the original Zelda was so antithetical to a guided experience. Sure there are numbered dungeons and even one that requires an item from another to gain entry, but the closest dungeon to the start (arguably) is the one marked “2,” and there’s nothing to stop you from entering it.

So what might have looked like a technical limitation initially ended up being a source of liberation for the Zelda series. As Kingwell states how the interaction with finite games is governed by their conclusion (think of games that bait you with multiple endings, how the result is dependent on very specific interactions within the game, and how a player is rewarded with this ending by behaving a very specific way), at what point does a game lose its sense of play? In a game like the original Zelda, and especially in BOTW, play is created by the absence of organized form. To free-jazz enthusiasts (and many, many other art forms) this is definitely not a new concept. Even to video games, hell, even to the Zelda franchise it’s not new. So why then does BOTW’s sense of play give me the feels so much?

Here’s an example: BOTW contains a physics engine that lets you essentially “break” certain puzzles. There’s a puzzle in one of the game’s shrines that works by way of the motion controller; you attempt to move a ball from point A to B by rolling it through a maze. However, if you take your controller and flip it upside down, the maze turns around as well, revealing a maze-less, smooth backside that makes guiding the ball to the point much easier (at least for me). But no approach to this puzzle is exactly the same; I’ve watched videos of people pan-flipping the ball like a fried egg to its goal; I’ve seen people try and hit it like a baseball as it dropped from the sky; and I’ve also witnessed some genius bomb Link over the wall that blocks you from the shrine's reward, ignoring the puzzle altogether. At first discovery of these type of "breaks," I thought I was some sort of genius (obviously delusional). Eventually (and after subsequent updates to the game), I realized that this is exactly what the game designers wanted. BOTW puts its focus on a physics engine over a constructed puzzle, hoping that a self-directed experience will be greater to share than every last one of us running through the same pattern, boarding up the experience with the word SPOILERS.

Thanks to the time investment required of video games, merely watching a video of the game being played is akin to playing it these days, albeit saving our already strangled-for time. Hell, I've done this in the past, mostly because the notion of experience in gaming has become so tied to narrative and plot that we bowed out of "playing" video games. Why play a Silent Hill game for all five different endings when you can play it once and watch the other four on YouTube? On top of that, games have continuously had to bait players into rewards for playing them, leading them down horrendously convoluted plot lines (Resident Evil). I'd even argue that the loot boxes we so loathe today are part of what we've come to expect with being rewarded (sure, it takes advantage of us, but we also expected rewards; companies just found out how to monetize that desire, which is what they're best at). If the dearth of awful video-game movies isn't enough to convince you that gaming’s true strength is not in its plot, then I'm not sure what will.

As far as plot goes for BOTW, it seems to be the first game in the Zelda series that acknowledges its redundant nature, and then asks the player, "Why are you looking forward to this ending? It will happen again, as it has over 10,000 years (as in 18 games in the main franchise dating back to an idea started in 1986)." Not to say it doesn't fall into its own history in a way that isn't somewhat conspiratorial ("Is that Ganondorf's horse? The large one?"). I'd even argue that a person who never completes BOTW enjoys it just as much as the person who does, as I’ve seen whole communities built on the experience of speedrunning the game (current record around 40 minutes — that’s starting the game and beating the final boss), on collecting the game’s 900 Korok seeds (which contains the ultimate fuck-you to reward seekers Korok shit), and even on a dedication to just doing goofy shit.

Expectation colors experience; try as hard as we may, what we expect will always bleed into how we see/hear/read anything placed in front of us. Every now and then, we experience a work of art that goes out of its way in both methods subtle and unsubtle to break us from this cycle. It might be outside of the realm of possibility to be a true blank slate and, in the reality of humanity and history, only possible in ignorance, but it’s often a work’s subtler transgressions that last beyond those of a more obvious flavor. I can’t help but think of works by Cage when I play this game, and it might be that a video game’s strong suit is how far removed it is from the problem of authorship/auteur theory. BOTW is not a new entry into this idea, but rather a reminder of what was there while we were taking an artistic format for granted as a children’s toy. Maybe BOTW will signal a movement into which we quit expecting to be constantly rewarded for participating in a work, asking that we turn inward to study our own experience rather than constantly criticize works on the grounds of delivery and feed. Cynically, I doubt this, but if I could interact with every artwork at the level on which I can interact with BOTW, both myself and the experience will be better off for it.

Credit to Joe Davenport for bouncing off ideas and helping me find secrets.

Welcome to Screen Week! Join us as we explore the films, TV shows, and video games that kept us staring at screens. More from this series