Max Jaffe’s work came to my attention via the strange, polymorphous, plastic, and elastic collective venture that is JOBS. Their 2018 album Log On For The Free Chance To Log On For Free suggested an elaborate, mutable thesis on how a band can sound and function in this goopy pre-post-human world. His latest project, a solo excursion resulting in an album called Giant Beat, is an equally captivating contribution to the burgeoning contingent of solo drummers experimenting with electronics.

We discussed that (and more) below, before Jaffe embarks on his first solo tour.

I wanted to first ask about your earliest experiences in music and your background in music. I know somewhere in the liner notes of Giant Beat, it says you’ve been hitting stuff since you were a kid.

My earliest memories are standing at a cupboard underneath the sink that I’m as tall as, drumming on my chest. My dad played drums enough to get me interested when I was young. He never did it professionally or anything, but there were drums, so I would just sit in front of the kit while he was playing along to whatever record. You know, Santana records or something. I just really absorbed the energy of this pretty special thing that my dad was able to do… in the context of otherwise being a pretty normal dad. My mom played piano too. She recently just got a new teacher. It’s also a hobby for her. It was always a social thing, very much between my brother and I, but also with friends up the block. We started a little band once we discovered other kids could play some instruments. I was like 9 or 10 years old. Then we moved towns from elementary school to middle school. We had to find new friends and got into Blink-182 cover band and stuff like that for a few years. We met a few friends who were really passionate about music and really cared about making original music. And in Burlingame, California for a few years, there was something in the water. There were bands that were seniors when I was a freshman. They were something to aspire to when I started a band with other freshman. I don’t know if every high schooler who gets into music has that experience of already looking up at somebody else and being, like, “yeah I can do that.”

Was it specifically the music they were doing or was it the fact that they were doing it?

For me, it was both. There was this particular band called What Life Makes Us. They were doing a post-hardcore type of thing, but I just wasn’t like exposed to anything beyond what was in Burlingame. That opened my ears up, because before that, I was into 311. So it was actually local bands that were my entry to what was going on around the country and around the world at that time.

I want to talk about Giant Beat a bit, and also I have some questions about JOBS. Can you tell me a bit about what Sensory Percussion is and how you interact with it as an instrument?

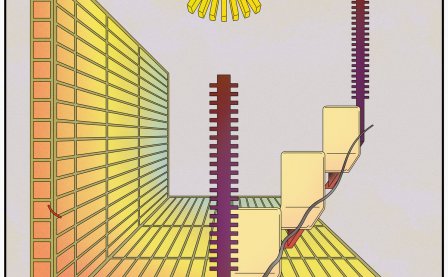

Well, there’s a lot written about what it is, how it works — I don’t need to really explain that. But I came into it because I had been using electronics in JOBS, and I know the founder of Sunhouse, Tlacael Esparza. Now that I’ve been working with Sunhouse probably longer than I ever worked with an SPD [a common drum trigger pad made by Roland], I do feel like it’s a lot more integrated into the mental flow that I’ve developed as a drummer.

How so?

Working with an SPD always felt like a separate part of my brain that I had to maintain. I was working with samplers so it was just kind of memorizing what pad is what sound. It’s a blank slate, so every bank of sounds is going to be set up differently. It might not always be intuitive and sometimes if you mess it up, depending on the band and depending on how dependent on the SPD they are, it can really mess things up. It could be awful. An SPD is often a live solution, and Sensory really feels like an instrument — it integrates into how I am already thinking or not thinking when I am playing; I’m able to really use my ears and my instincts. There is still some work that has to go in ahead of time — building the kits and creating the sound worlds — that’s very different from practicing drum set. But the more I work on new pieces, the more I feel like I’m learning the software as an instrument too. It’s all feeling more natural, whereas with a lot of electronics, there’s a lot of memorizing steps. It kind of keeps you a little at a distance. There is some of that, remembering, “This kit is set up this way. If I hit this part of the drum, there’s gonna be this sound, but if I hit this other part of the drum, it’s going to manipulate this sound in this way.” I have to remember how each kit works, but once I hear the sound of it, it’s like muscle memory: there’s a world that I’ve built, and there are certain maneuvers within that world that create certain textures that I want, and that feels a lot more natural and a lot more related to drumming itself.

That actually brings me to ask, with the tracks on Giant Beat, to what degree would you say they’re composed? Is improvisation a part of it? How much are you shaping it beforehand as a song?

They were all single-take performances, so each time I play a show, it is a little different. My background as an improvisor led me to leave space in every set to improvise with myself, but because there’s a lot of work ahead of time to build the kits, there is a lot of compositional decision-making that happens before I hit record. I do kind of have a sense for how I want things to flow, and because I have to remember how certain kits are built, there were certain maneuvers and gestures that work in a certain way to elicit a certain sound or loop or effect. I could play them totally differently, and to me, it would actually be a different piece of music, or it would be a remix or something, if that makes sense. If I played the same kit and played something just rhythmically with my body, that to me would be a different piece.

Yeah I guess that’s what I was wondering: how much of a composition was just the kit, or was it the kit plus this sort of beat, or was it when an overarching form takes place?

Yeah, some more than others. There’s some where there’s harmonic loops or sections that I’m thinking of as verses or choruses. And then “The Rake,” I thought of as a duo with a guitarist. So I just chose a sample that I made that had a lot of variety, and then I introduced a lot of randomness in the program, so that, one, I just hit this thing, and then I just kind of play with it.

So, for a lot of it, you’re sampling collaborators. Is that something you recorded in the process of making these kits, or are you pulling from other recordings you have?

Yeah, a lot of it was practical. When I started working with the program, I had basically what came in the box and then a few folders of drum samples that Shannon Fields [from Leverage Models and Stars Like Fleas] gave me, and that was about it. Then I started digging into just other sorts of sample sources that I might use, and then from that, I started thinking more specifically about friends and using that space as a sort of way to collaborate with people across distances and time. I have a few friends who are actively building sample libraries all the time, so I started with them. It started to become this way to… I don’t know, I’m a sentimental guy — I can be. And it became this way to inject more meaning into each kit and each soundworld, even if it was just for me. To give a little more intent to each performance, and it would help me just emotionally shape it more and assign more meaning to each thing and have it be more than just “this sounds cool.”

Rather than the end goal necessarily being to just make the coolest, hottest track — and of course, there’s room for functional music like that — but for you to be able to connect to it in a more personal way.

Right, even if it’s just for me. Because instead of just going blindly into the world of samples, you need some sort of parameter. For me, emotional ones work and technical ones work.

Right, to give yourself some grounding.

Yeah exactly. I mentioned those pedals I got in the mail today; now I’m starting to think, for another recording, how to introduce more elements outside of Sensory that are providing more surprising elements that I can be in duo with. So I’m not controlling every last part of it. Basically, to create an additional layer and a rhythmic element beyond what’s happening in Sensory as a way to potentially get more texture out of the sound and to change things on the fly. It can be sometimes hard to make drastic decisions in Sensory that aren’t total kit- or piece-changes. Once you’ve built the world, it can be hard to take a total left turn if you want to without changing the kit. So, now, external effects can maybe do more than just a jump cut, for one example.

Totally. So, I also wanted to ask for your thoughts. I’ve been noticing there’s a good group of drummers and percussionists who are doing this sort of solo work — especially engaging with electronics — and I think it has to do with these electronics getting more interesting, where it’s not the type of electronic drum kit you might play in Guitar Center…

Right. Which, still, I can’t resist any time I’m in Guitar Center.

Yeah, they are sick, I’m not even a drummer and I sit down… But I also think, in addition to that getting better, it has to do with musicians seeing the musical idiom actually being available and even seeing the listening context being available for this sort of electronic and experimental music. A few of the people I’m thinking of are Eli Keszler, Booker Stardrum, Weasel Walter, and Deantoni Parks. I was wondering what you think of it: if it’s a moment or if there are people who have been doing this for a while that I’m not hip to or what.

Yeah, well, I don’t know. Obviously I don’t want to think of it as a moment. I don’t think of it as a moment. I think of it as a culmination of a bunch of factors. There are definitely some people who come to mind: there’s Scott Amendola, he plays with Nels Klein in the bay area. He’s done a lot of stuff with contact mics and effects pedals for a long time. I think Sensory Percussion is definitely a game-changer for a solo drum set. There’s a couple of people that I thought you would mention, but you didn’t. There’s Ian Chang, Greg Fox… As soon as [Sunhouse person] showed me what he was working on, I was like, “OK, this has the potential to change things.” I just thought about SPDs and it being this thing that is now quite ubiquitous, probably 20 years after release. So like imagining Sensory 20 years from now… I think it’s just the beginning. I think this will be more and more a way for drummers to express themselves musically. I hope. I am surprised at how niche it still is. But I think there’s a good amount of the drumming community that is still more interested in chops than technology that can allow drummers to do more solo electronic composition. So maybe it still is just a niche community that this particular thing appeals to, but I’m kind of surprised that every drummer in the world isn’t freaking out about it all the time.

I think something interesting is that it’s this impulse for drummers to do a set by theirselves comes just at the time that there are less and less drummers in bands, it seems. Not that drummers got kicked out of the scene and are thinking, “What are we gonna do now?” I mean, we are all megalomaniacs and horrible to work with.

True. But, I guess, hearing you talk about where Sensory could go and also thinking about what you do in JOBS, thinking about how drummers adopting these things could make a good case for musicians to realize it could make their band a lot cooler.

Yes. Which is why I’m trying to work it into as many situations as possible rather than just solo. Because a lot of the stuff that I’ve seen, I guess at this point in time, some of the people you mentioned — Weasel and Deantoni Parks — they don’t use Sensory, and they’re doing really awesome solo stuff. But with Sensory, the more people use it in a variety of settings, the more it will be embraced. Because maybe not every drummer wants to embark on a solo career, they like being in a band, and they just want to push what that band is capable of musically. I use it in JOBS, I use it in Elder Ones, and not for any reason other than what I think is needed compositionally for those groups. It is interesting now that I’m embarking on this solo thing — I’m planning a solo tour for this summer. And I have given some thought to what you’re saying about how there seems to be a surge in solo drummers, and at the same time, there seems to be more and more bands without drummers. When I think about the social aspect of music, I sometimes worry if there’s something that is lost in a solo endeavor. It’s new to me, so the groups I play with have become more important to me. I try to keep that communal performance experience.

There’s something about JOBS’ music, especially on Log On For The Free Chance To Log On For Free, that it feels like it didn’t come from one person; it sounds much more amorphous than what you usually get from someone who’s writing songs, who knows their voice, who has a goal going in. It has more of a quality of experimentation within the process. I wonder if that understanding matches up with how JOBS functions.

Totally. I’m really happy that came across, because we really pride ourselves in the collective aspect of the group. We like having that reflected in the music as well as onstage. That’s the whole vibe. I guess a lot of it still will come from one person being like, “Here’s a thing.” I’d say, at least on that record, 60% of it or so came from something Dave wrote on his own. I think part of why he and I have been on a similar wavelength since we met is because he is really not precious about his material. As a collaborator, as a drummer, my way to shape the music — other than hitting the drums — is more through conversation with the others I’m playing with. But yeah, he isn’t very precious about the material. He might bring in a full score, and we’ll play through it, and I’ll be like, “Dave, we’re not playing this for a show. What is this. But this one measure is really sick; what if we loop that and that’s our verse?” We’ll take a more granular approach to something fully scored out, and at the end of it, it is a collaborative song but began with a full score that doesn’t sound anything like the final version. And then there’s other material coming from the rest of us as well, so with all that combined, I think our voices are pretty clear collectively rather than individually.

More about: Chrome Sparks, Elder Ones, JOBS, Max Jaffe