Pop Eats Art

Two further releases however, indicate that, in 2013, something slightly more complicated was going on in the world of pop.

First, Lady Gaga’s much-anticipated ARTPOP was released. Whereas the teenyboppers were making pop that laid out the parameters of their music from the inside, Gaga’s release was explicit in its attempts to make pop that was not just about itself, but about something else as well: pop that was also “art.” As the press release triumphantly announced, this was an album that would “bring ARTculture into POP in a reverse Warholian expedition” — “Pop culture was in art; now art’s in pop culture, in me.” According to Gaga, it was her “dream” that “art and pop should come together” (without the slightest recognition that the thought had occurred to anyone before).

To realize “her” dream, Gaga collaborated with contemporary pop artist Jeff Koons (who else?) to host a so-called “ArtRave” in Brooklyn for a few hundred lucky “Monsters” and industry-types wherein people danced to Gaga surrounded by gigantic sculptures and photographs made by Koons, mostly of Gaga. On the album cover (also by Koons), a naked Gaga sits surrounded by jagged fragments of classical sculpture and Sandro Boticelli’s The Birth of Venus, while cradling between her loins a giant blue sphere — one of many that adorned Koons’ new body of work in 2013 — in whose reflection we see the art studio or gallery in which Gaga is sitting. The message here is hard to miss: this album is not just about pop — this is pop about pop being pop and art.

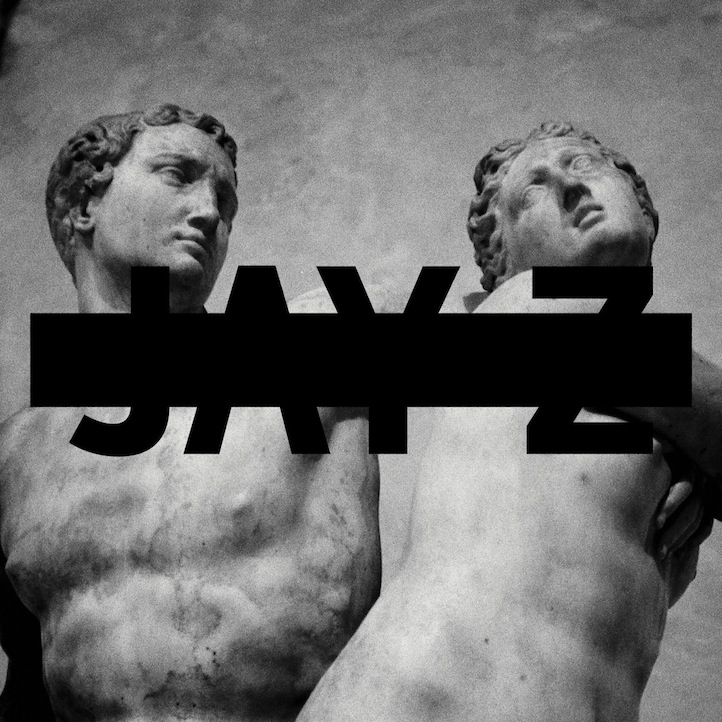

Earlier on in the year, by way of promotion for his latest release Magna Carta… Holy Grail, Jay Z exhibited copies of the album alongside one of only four surviving copies of the original Magna Carta at Salisbury Cathedral. Soon after, he released “Picasso Baby: A Performance Art Film,” which had been recorded live at a New York contemporary art gallery and which saw the founder of Roc-A-Fella records performing the album track “Picasso Baby” to individual audience members, one after another, over a period of six hours: a glitzy hip-hop re-imagining of Marina Abramovic’s well-known “The Artist is Present.” And self-consciously so. Abramovic really was present.

In 2013, then, pop not only continued to perform its own pop-ness (Madison Beer, Zendaya, One Direction), but, in the histrionics of Gaga and Jay Z, this project became the music’s main goal. Indeed, this project was pursued to what some considered the sacrifice of the music itself — Gaga’s album in particular was not only panned by critics, but also seemingly by her fans and the market as well2. Jay-Z and Lady Gaga turned all their attention to the question of their music’s “pop” status, not by performing its musical attributes, but by attempting rhetorically to frame their popness, to step outside pop to some extent and hold pop up against something else — in this case art3.

Art Eats Pop

The mobilization of music’s art and/or pop status has not only occurred on the pop side of the fence.

In June 2013, Nick Newlin, a Chicago-based musician and student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, released Revengeance under the name Yen Tech. It’s an extremely weird listen. Revengeance glistens with all the hallmarks of a contemporary mega-pop chart-topper — thumping euro-trance beats, rushing synth buildups, and the slick tones of Yen Tech’s hyper-produced voice delivering the kind of self-reinforcing banalities we discussed above: “Feel the rush of the wave/ You’ve got one life/ Go hard to the end, ye-eah/ I play the game to win/ I’m gonna set it off/ I’m goin’ up, goin’ up, goin’ o-off/ I take my drink and I raise it up/ We got one life, gotta live it up.”

Pretty quickly, the record becomes hard to listen to. It’s just too much, like being force fed can after can of Red Bull. Although Yen Tech’s music comes very close to being indistinguishable from a mainstream pop release, it’s this sense of overload, this excessive quality — in a pop landscape, moreover, which is already excessive — that alerts the listener to the fact that it is not, or not only, pop. Something else is going on here.

As Adam Harper points out, Yen Tech’s album is an artistic pastiche of pop music. However, as Harper explains, it inhabits pop music’s affects and discourses to such an extent that the gap between pop and art becomes almost indistinguishable — there are only a few clues (Newlin’s enrollment in an art school, his links to the deliberately arty and ironic DIS magazine, YouTube hits4) that the album is indeed not just another pop album. Yen Tech is, of course, only the most recent in a train of such performances, including HD-Boyz and ADR. In the best tradition of pop art, from Andy Warhol to 1980s appropriation artists and musicians, to Jeff Koons himself, these artists are playing with the almost imperceptible line between pop and art, reducing this gap until it is so thin that we can’t even really hear it any more; we can only think it. The difference is more a matter of attitude than sonics.

But when considered in a broader context, what is most interesting about Yen Tech et al.’s conceptualization of pop into art is that it is occurring at a time in which pop itself not only already conceptualizes itself, but also very publicly tries to move in the other direction, conceptualizing pop so that it can also be art. So no longer is it only art that is blurring the line between art and pop — pop is (however naively) attempting it too.

We All Eat Everything

Before we finish the first part of this essay, it’s worth zooming out one more time to consider the technological context in which both of these musical maneuvers (pop eats art, art eats pop) are taking place.

Whatever the web’s many sins, it is still at least mostly neutral when it comes to content. The result is a kind of equivalence in terms of accessibility between the popular and the not-so-popular. One result of this equivalence has been a massive increase in the accessibility of independent culture. Even Spotify doesn’t care whether you listen to Katy Perry or Keith Fullerton Whitman, so long as you’re not on BitTorrent or iTunes. And the result is that it’s become increasingly easy in recent years to simply switch off: quite literally to tune pop out.

However, the paradoxical result of this new pop/non-pop parallelism has been a kind of exoticization of the mainstream. If you spend enough time with all that noise, drone, UK dubstep, and minimal techno, if you tune out from the mainstream for long enough, then suddenly it’s the Top 40 that starts to sound foreign, to exert a certain exotic allure. After so much time away, it’s hard not to develop a certain appreciation for the finely calibrated pop hook, which no longer seems so debased. And if it’s hooks you’re into, why stop with either the present or the local? After all, there’s a good 50-odd years’ worth out there on YouTube to be mined if you’re interested. And plenty happening in Japan, South Korea, and elsewhere, in the present tense too.

Sure enough, we’ve seen a parallel embrace of these sounds by critics: a kind of latter-day global popism. Look at this very publication, for instance (in particular the work of Max Power), with its continued commitment to theorizing the likes of Gaga, Beyoncé, Lana Del Rey, Taylor Swift, Miley Cyrus, J- and K-Pop in and amongst all the weirdness. Or consider Pitchfork’s unashamed canonization of pop sounds.

In 2014, pop and non-pop feel closer than ever. Everyone loves pop these days. And they’re not ashamed to admit it.

2. In its first week, it sold only 25% of what Born This Way did in the equivalent period. And sales dropped by another 81% the following week.

3. The failure of both albums was due not only to the deficiencies of the music itself, but also to the fact that both artists placed such emphasis on the startling novelty of their rhetorical maneuvers, something that anyone with a passing familiarity with the history of art and music over the past 100 years was sure to find hard to stomach.

4. Whereas “Applause” from ARTPOP currently clocks in at around 140 million views on YouTube and “Bad Romance” has already notched up over half a billion, Yen Tech’s most popular video “Forever Ballin” has just 41,000, which is a couple of thousand less than this video of “Romeo the Skateboarding Cat.”

More about: ADR, Daniel Lopatin, Dean Blunt, Gatekeeper, James Ferraro, Yen Tech