Sam Amidon was born in Vermont to a household where music — and particularly traditional music — was an elemental part of everyday life. Amidon started on the fiddle at an early age, eventually immersing himself in the traditional Irish style. In mid-2000s New York, he decided to learn guitar and recorded his first record — But This Chicken Proved Falsehearted — with his childhood friend and longtime musical cohort Thomas Bartlett. This collection of smartly reworked takes on (mostly) folk tunes was released by Plug Research in 2007. Amidon followed Chicken with two albums of lushly produced interpretations, 2007’s All Is Well and 2010’s I See the Sign, both recorded in Iceland with producer Valgeir Sigurðsson and featuring striking arrangements by the prodigious young composer Nico Muhly. In recent years, Amidon married the British singer-songwriter Beth Orton and relocated to London, where the two had their first child together in 2011.

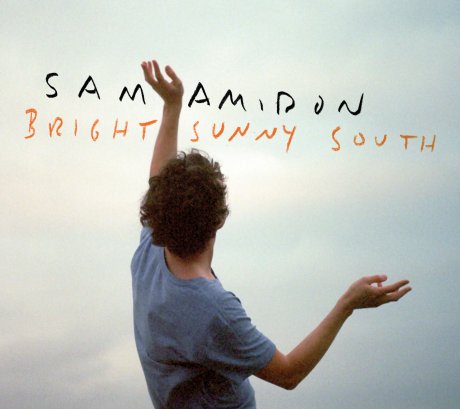

For his new record, Bright Sunny South (out this month from Nonesuch), Amidon decided to return to the more stripped-down sound of his debut, recording in London with a small group of friends and the English engineer Jerry Boys. The album features a diverse range of material, from the plaintive Irish ballad “Streets of Derry” to a stunning take on the Tim McGraw single “My Old Friend,” a dirge-like variation of Mariah Carey’s “Shake It Off,” and contributions on two tracks from the senior jazz trumpeter Kenny Wheeler.

Amidon is currently on tour behind Bright Sunny South, which he launched with a beautiful record release show at New York City’s Le Poisson Rouge on May 16. We spoke by phone the week prior.

I want to begin by talking about music when you were growing up. When did you first start playing fiddle?

I think my parents suggested fiddle because there was this insane teacher named David Tasgal. He was kind of nuts, but he had an amazing ability to communicate music to little kids. He happened to be a violin teacher, so I think they chose it in part because of him. He was definitely an inspiring figure for me, not only musically, but also because he had this slightly cracked sense of humor. He had this deadpan vibe that I thought was hilarious.

My parents were smarter than other parents — they never put the pressure on. They never said: “You have to do this.” But they completely bombarded us with music. Everybody we knew was a musician; we had instruments lying around the house; all of our holiday get-togethers involved music in some way. They always said: “You don’t have to get into music — you can do whatever you want,” but it was almost like saying: “You don’t need to breathe air.” It completely surrounded us.

They are also great critical listeners, regardless of genre. My dad gave me Bitch’s Brew as a gift when I was 13 or 14, and they loved Talking Heads. And because we performed together as a family, we would have these long car rides where we would listen and debate and figure out what was going on in music. It was something that we shared.

I couldn’t sing you a stock of amazing old ballads. I’m not a “folk singer” in that sense. I’m learning these songs as part of my own compositional process.

How old were you when you met Thomas Bartlett?

I met him when we were about 7. He was just starting on piano, and in a way he was as much the reason I stuck with music as my parents were. He was way more driven than me. I wasn’t one of those kids who practiced hours a day. I loved music, but I was more into basketball. But literally, at the age of 7, Thomas would say: “Let’s arrange this fiddle tune and see what we can get out of it. Then we can play basketball.”

That’s amazing.

Yeah, he was just one of those kids. I was a more normal, somewhat spacy child, but Thomas had that super-intense drive. And that stayed consistent. There were times when I may have drifted off and gotten into other stuff, but he was always there, pushing music.

Did you ever have a period growing up when you rebelled against folk, or was it always something that you loved? I know you eventually got into free jazz and improvisatory music …

Yeah — I did rebel, but in really specific and nerdy-sounding ways. Folk music wasn’t just one thing for us: there were traditional Irish fiddle tunes, Appalachian old-time fiddle and banjo tunes, folk contra dancing (which is a kind of folk dancing in New England), English folk songs. All that stuff was around us, and they were all radically different categories to us. From the perspective of one, you could hate the others. So my rebellion was getting so intensely into the Irish traditional fiddle style — as a kid I really didn’t like the American folk stuff at all.

Also, my childhood listening never involved a singer and a guitar. I hated the singer-songwriter model — we just didn’t see the point. I felt like you should either go play some deep fiddle tunes, or you should listen to Jimi Hendrix. I didn’t understand why you would do something in between. I’ve only really discovered Bob Dylan and Joni Mitchell in the last 10 years. I have no idea what my 12-year-old self would think of what I do now. We were much more hardcore then, you know?

Do you like Dylan and Joni Mitchell now?

Joni’s amazing. But I guess I came to her after having left folk music, and gotten deep into free jazz and rock. I’ve been able to come from that angle and appreciate what Joni Mitchell did as a sound artist. I don’t really hear the connection to folk. I understand of course that there is a connection, but for me it’s a whole different area.

It was the same with a lot of the American Appalachian ballads and old-time fiddle stuff that I do now. I wasn’t that into it as a kid. It’s scratchy and raw, so it sounded incompetent to me. Again, it was kind of through free jazz that I was able to appreciate it. I had to listen to Albert Ayler first and hear the intensity of his raw, weird, can-he-actually-play-his-instrument-or-not saxophone playing before I went back and heard old-time fiddle and realized: “Oh, this is the same thing — I understand now.” I think a lot of people went through this in the early 2000s with the freak-folk movement. People realized there was a connection between outsider free jazz and some weird dude on a mountain having a holler. So I was the same as a lot of other people at that moment, but the only thing that was lucky for me was that when I came home with a Dock Boggs CD, my parents were like: “Yeah, we have that on vinyl.” Or my mom had already been singing some of those songs. So it was already a part of me in an unconscious way.

You only first started playing guitar and singing in kind of a “singer-songwriter” way in the lead-up to recording your first album, right?

Yes, exactly. Thomas and I were in a somewhat unconscious state of exploration with But This Chicken Proved Falsehearted. It was the first time he was “producing” something. We borrowed a Pro Tools setup from Oren Bloedow, and I think Thomas borrowed the keyboards from Yuka Honda. He was just starting to play around with different bands in New York, and I was learning guitar. I started writing on guitar and re-harmonizing folk songs as a way to get myself into writing songs, and I just got stuck at that stage. The reality is I don’t think I was actually that interested in writing songs. I was just taught that that’s what I was supposed to do—it’s that arbitrary notion that we’ve had since Dylan.

Right. And you two recorded Chicken at home?

Yeah. Thomas was much busier than I was at that time. He became very in-demand as a musician, and I was still finding my way. I was spending a lot of time in the house alone strumming the guitar, kind of depressed. I would have some whiskey late at night and I would put the songs down, almost like a self-inflicted field recording. And we used the take where I made the least mistakes — that was literally our only criterion for quality. Then Thomas would start adding shit on to the songs, but he was really shy about it — he didn’t want me around when he did it. He was like: “You have to go. Take a walk or something,” and I would come back an hour later and there would be some crazy stuff on there.

That’s interesting.

That was kind of the model for All Is Well, too, even though that was a much more ornate version of it. But it was actually the same thing, with blind additions and accidents happening without any warning.

But Bright Sunny South was different?

Yeah. I did a couple days solo first because I wanted to enter that space a little bit, then the boys came: Thomas, Shahzad Ismaily, and Chris Vatalaro. We were all in the same room, and a lot of it was essentially done live.

When I listen to the noisy freak-out at the end of “He’s Taken My Feet,” for example, it definitely sounds like you guys are playing as a band.

Right, that was happening in that moment.

What was working with Jerry Boys like? It seems like maybe he takes a more documentary approach, as opposed to Valgeir Sigurðsson, who you worked with in Iceland?

Jerry came in as an old-school recording engineer. It was about documentation and capturing sound in its clarity and rawness. I almost felt like he was field recording us, because we didn’t have much shared musical context — except that I’ve listened to Martin Carthy and other English folk shit he recorded in the ’70s, or the Ali Farke Touré and Toumani Diabaté duo albums he did, which are so beautiful. You just hear two instruments on those records — it’s so simple, yet there’s so much detail. That’s something that interested me a lot about Jerry.

So it was cool because he was kind of an outsider, but he could still always tell when something was happening. He could sense whether there was a vibe, and he would tell us. He actually had a very open, somewhat playful approach. He had no sense of genre context — he’s not an indie rock person — so to him we were just these odd people doing these odd things. But that gave him a fresh sense of whether it was working.

It was also an interesting environment because Thomas and Shahzad and Chris and I had not played together as a band. I have intense duo relationships with all three of them: Thomas and I did the Chicken album together; Shahzad and I have improvised together and traded music lessons (like a banjo lesson for a guitar lesson); and Chris is my fellow expat here in London, and we’ve done a ton of touring together as a duo. They’re all multi-instrumentalists, and each has a very specific sense of what I do, and how what they do relates to it. So throwing everybody together was kind of odd. People were thrown a bit off balance and were trying not to step on each others’ toes. I kind of liked it — it felt very real when we pushed it, because people were really listening to each other.

I listened to an interview you did recently with The Guardian wherein you were asked what makes this album different from I See the Sign, and you said that it comes from a more solitary place. I definitely agree, but I also think it’s a more open record in some ways. It’s very exploratory, and each song is a little different — as opposed to the Iceland records, which felt like these enclosed, consistent worlds.

I hope it’s a bigger range in a certain way. You could say there are two kinds of albums: there are albums that are more like one space that you go into and stay in for 40 minutes — that set a tone and an atmosphere from the first moment and stay there the whole time. That’s a really lovely thing for an album to be, and hopefully Bright Sunny South has an element of that. But I wanted to do an album where it would have radically contrasting sonic environments, but still feel like it’s all coming from one creative space. We really focused on the content of each moment, and what we could get out of each moment, while still trying to make it feel like a whole. Whether I succeeded or not is up to people to judge.

I definitely think you did. I also think within these songs, there are moods and textures that are quite different from what you’ve released before. For example, the song “Pharaoh” kind of has a world-music vibe.

Yes, that was amazing. Shahzad and I started playing this super hippy-dippy California thing, and Chris just pulled out a flute. He was like: “Oh cool, I brought my flute!” [laughs] It was this surreal moment where we were like: “You play flute? What?” So we just got into that space. It was interesting …

I have no idea what my 12-year-old self would think of what I do now. We were much more hardcore then, you know?

So, I made kind of a concerted effort to find previous recordings of all these songs —

Oh, great! That’s fantastic.

I think I succeeded in most cases, but there are a few I’m not sure about.

Which ones were you having a harder time finding?

Well, “Pharaoh” was one.

“Pharaoh” is from the Alan Lomax Collection, and it’s a recording of a woman named Sidney Carter. It’s just totally a cappella [Sam starts singing a couple notes from “Pharaoh”]. That’s one of the more radically changed songs on the record.

How about “He’s Taken My Feet”? I found a song with somewhat similar lyrics, but it’s more of a ’50s R&B type thing [Brother John Sellers’s “He Took My Feet Out of the Miry Clay”].

No way! You’ll have to send that to me.

“He’s Taken My Feet” comes from one of the more frequent sources for me, which has been very fertile for melodies and music. It’s a very beautiful album called Sharon Mountain Harmony, which, as it happens, my parents sang on. But a lot of it was this woman named Lucy Simpson, who was a friend of theirs who lived in Brooklyn. I don’t think she was a professional musician — I’m not sure what she did for her day job — but she was a folklorist and singer, and she would go poke around people’s attics and find old hymn books. She uncovered some incredibly beautiful hymns, and she sang with a lovely, unadorned, very compelling voice. Sharon Mountain Harmony came out on Folk-Legacy Records in the ’80s, and I think it’s still sort of in print — you can order it on CD from their website and it comes hand-burned. It’s also where my parents recorded “True Born Sons of Levi,” which is on the Chicken album, and the words to the “lost sheep” song at the end of I See the Sign [“Red”] came from another song on that record.

What about “As I Roved Out”? All the versions I’ve found are relatively quiet, and kind of plaintive.

Right, and very Irish-y. That was from a wonderful friend of mine named Bruce Greene, and his wife Loy McWhirter. Bruce is a fiddle player who lives in North Carolina, and he went around eastern Kentucky in the early ’70s learning fiddle from guys who were 80 and 90 years old, who had learned their tunes from Confederate veterans and ex-slaves. He found — almost by accident — this whole swath of fiddle players that other folklorists had missed. Bruce and Loy are very deep musicians, and they have an album of a cappella ballads called Come Near My Love. It’s somewhere between Alan Lomax, John and Yoko, and Albert Ayler. It’s only their two voices, but the harmonies are really weird and beautiful, and they sing these seven or 10 verse ballads — really dark, long, strange murder ballads. He sings the song on there [Sam sings the opening line of “As I Roved Out”]. It’s a quiet, sing-to-yourself type of thing, but there’s a bit of humor and intensity in the way he does it that sparked something in me.

When do you decide to radically change a melody or write original music, as opposed to doing a relatively faithful rendition of a song?

Well, sometimes I’ve just written something — like “Short Life” on Bright Sunny South, for example, was music that I just came up with. I had that guitar part, and I was humming the melody in my head, then I brought in the words. Other times a melody from an old song gets stuck in my head first, but it’s more common that I come up with a guitar part. Then it’ll occur to me that there’s a melody that works — usually it’s something that’s been kicking around inside my head recently. It’s quite random, because sometimes it’s in the wrong key, and I have to change some of the notes. It grows symbiotically from there; both the music and the melody get moved around together.

You know, I’m not a folk-song expert. If we were sitting around and people started singing ballads and songs, I could do the songs from my albums, but I couldn’t sing you a stock of amazing old ballads. I’m not a “folk singer” in that sense. I’m learning these songs as part of my own compositional process. I’m a fiddle player — if we sat down at an Irish session, I could play you a thousand Irish tunes. I could sit here and play you Irish tunes all day. But I’m definitely not an expert in ballads or folk singing, and I’m not a folklorist. I love this world, but I listen to old ballads as an outsider. I listen to it the same way I listen to Miles Davis or something like that — it’s a deep listening experience, but it’s not something that I know a lot about.

The last thing I’d like to ask you is how the Kenny Wheeler collaboration came about.

Well, I knew I wanted to have some other person appear on the album — some outside musical force. I really wanted Bonnie Raitt — I wanted her to play a slide guitar solo in the middle of one of the songs, because she’s such a fucking badass guitar player. She sent a very kind note saying she couldn’t do it. I think it was Chris who mentioned that Kenny Wheeler lived in London, and (probably as a joke) said to me: “We should call him up.” His 1975 album Gnu High, with Keith Jarrett and Jack DeJohnette on ECM, is one of our favorites. These musicians had very strong free-jazz backgrounds. They were playing melodically, but you can feel in the intensity of the timbre that they had that free-jazz thing behind them. So I got his number, and I was so nervous to call him. I got him on the phone, and I was kind of rambling on: “Hey, my name’s Sam and I sing folk songs, but I kind of change them around, and I’m doing this album for Nonesuch, and I play with Bill Frisell” — you know, just trying to make myself sound like somebody he wouldn’t hang up on. And he just cut in eventually: “When’s the date!? When is it!?” [said in a funny older man voice]

He’s in his early eighties. I think he’s basically retired, although he does still play around London occasionally. He moves quite slowly, and I wasn’t sure how it would go because trumpet is such a physical instrument, but as you can hear he was just shredding. It was hilarious — he was overdubbing his part [on “I Wish I Wish”], and we pressed play and he started playing and didn’t stop until the end, regardless of whether I was singing. He literally played the whole time, so we obviously needed to take a lot of it out. When I was listening to it, it was all very vibrato, out-of-time playing, so we thought we could move it around. But once we started carving it out, everything he did needed to stay where it was — it was perfect in its moment. If you heard the raw file of him playing, you might question whether he was listening, because he was playing right over the vocal. Yet his playing is so responsive to everything else that’s going on around it — he was definitely listening. He’s a really sweet guy.