Authenticity and the monetary exchange value of information

Hyperassimilation has emerged as a means of processing an overflow of sonic data, and the resultant aesthetic was just as controversial, if not more so, than the current buzz around Normcore. Remember vaporwave? Although I know some at TMT would like to forget it even happened, the way the deliberately “inauthentic” genre trolled our sense of critical integrity has changed the way we perceive new sounds, rendered us less immediately trusting of the idea of artistic intent.

Vaporwave started out like any internet genre, with enough artists doing the same thing until someone decided to call it something, but the genre’s rise to think-piece prominence was unprecedented for internet phenomena in that there was actually a method behind the music apart from “triangles, screwed trap beats, and witches” or “dolphins, club music, and virtual palm trees.” If it seems like I’m deriding witch house and seapunk, I’m not; I think it’s crucial to recognize that even though these genres had a virtual point of genesis, their methodologies were only hyperaccelerated, digitally-informed cousins of indie music — a heavily ironic, recklessly appropriating pastiche approach, still grasping for a kind of self-aware uniqueness even as it began to acknowledge the inevitability of influence.

Vaporous imagery

Vaporwave took the internet genre’s small admission of homogeneity and sped it toward its logical conclusion: by sampling sounds that were overtly bland and homogenous — the kind of cheesy, MIDI-laden Muzak that exists to accompany corporate PowerPoint presentations and elevator rides, to generally lubricate the movement of capital through our global economy — vaporwave artists were able to toy with the concept of “enjoyment” and where it comes from. If deliberately bad, formulaic music can be teased to reveal a kind of humorous beauty, why should we assume that “authenticity” is a good starting point for good art?

In the soft-focus style of media consumption, one treats every piece of media as if it were merely a fraction of a larger dialogue, which it is your overall goal to comprehend. Every aesthetic gesture you notice can be thought of as engaged in play with the aesthetic gestures of all media surrounding it.

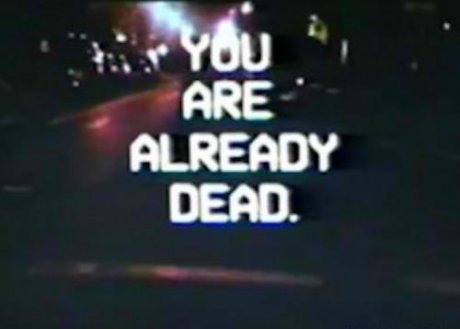

The ambivalence or otherwise complete absence of artistic authenticity in vaporwave was matched by the contextual markers that framed it for audiences — most of its “star” artists were anonymous, taking on post-human monikers that sounded like global corporations or computers, and in its most perfect form, it was the sound of total indistinctness, a homogenous, free-floating particle of “art”: vapor. Vaporwave flourishes in the tragedy of 21st-century capitalism: that every piece of information, whether conceived as “art” or “product,” can ultimately be reduced to a monetary exchange value. Everything is always already the same, regardless of what we wanted it to be.

In lots of ways, Normcore is the aesthetic realization of the vaporwave gesture on a fashion level. Rather than decrying corporately produced materials as somehow less authentic than artisanal ones, it recognizes every material good on earth is subject to the same global capitalist economy, and so no form is less authentic or inherently “unique” than another — we are all equal amounts the same.

Hyperspecialization: the extreme “cool”

Hyperassimilation is but one of the possible responses to an oversaturated information economy, however. Another possible (and rather common, from my observations) response is hyperspecialization, or, extreme self-identification with a set of particular generic tropes, focused on the continual, gradual development of tropes within a singular aesthetic. I myself have an experience with hyperspecialization, as in late 2012, I started a blog about the then-Chicago-centered phenomenon of footwork music. This was after DJ Rashad’s game-changing Teklife Vol. 1: Welcome To The Chi came out, but before all the widespread coverage of the genre in the UK press and elsewhere, before the genre began to gentrify with the gradual introduction of UK production values and the increasing globalization of its production-base. This was a fascinating phenomenon to observe and write about, and I don’t regret the time I spent with my ears locked into 160 bpm, but I also don’t deny that after several months of poring through SoundCloud, grasping for even minute signs of intra-genre progression, I began to get the feeling I was missing the forest for the trees.

The advent of this realization was maybe spurred on by my experience in promoting my writing through social media avenues like Facebook, Tumblr, and Twitter: my audience expanded exponentially at first, but after awhile it hit a wall. I believe the sudden ceiling I hit was due in part to the specificity of what I chose to focus on: I was no longer listening to music for difference like I used to when I was a teenager. I was listening for sameness. I had so completely internalized the tropes of footwork music — the stuttering, polyrhythmic triplets; the coyly, gradually unfolding song structures; and the intensely anxious tone of the music — that my very definition of “music” had shrunken to sounds that included those tropes. I was coming dangerously close to becoming the kind of technocratic, close-minded nerd I’d learned to disregard and was losing my point of reference when I’d talk to friends about new music or emerging trends in art.

Footwork dancing at Chicago underground venue Battlegroundz

It’s easy to make these observations now because footwork music, though it remains sonically pervasive in a subtle way, has somewhat run its course in terms of development and potential to influence. Indeed, most of the tropes laid out above were set into place long before footwork “broke” to a larger, mostly virtual audience, back when it was an aggressively underground Chicago dance scene. At the time I began writing about it, however, footwork’s multi-limbed fury sounded positively futuristic when it was recreated over and over again, in a series of progressively universal, less “shocking” iterations, until it began to constitute the norm. Again, the post-human arc of aesthetics had successfully appropriated its fringe elements into the mainstream, and it did so without respect to my conviction that the genre was inherently more “avant-garde” than others.

The confusion of a diachronic uniqueness with a synchronic one is a fallacy motivating countless “progressive” movements in art, and perhaps it is a necessary one. Even the recent Normcore article, entirely aware of the fact that its methodology depends on the fundamentally cyclical nature of aesthetics, speaks of dressing in a deliberately bland manner as a somehow novel, unprecedented way of being cool — to which I might contest that, if this is true, my father has been at the forefront of aesthetic experimentation for decades without being given his due. Jokes aside, being cool by not being cool is not, in fact, a new idea. It’s a reactionary counter-gesture that has been reenacted time and time again throughout the development of style; the only thing that has changed is the specifics that define what is “cool” and what is “uncool” during a particular section of diachronic time.

The Soft Focus

In today’s hyperaccelerated, hypersaturated data climate, hyperassimilation has begun to emerge in a serious style of prosumption across all forms of media. If “hyperassimilation” sounds too much like a word that you might hear someone repeat over and over again to sound smart without knowing what it means, I also like to think of the paradigm as a soft focus directed toward media — think of the way you might click on a link to a Buzzfeed article after being hooked by the title and then scroll through the page noncommittally, scanning the text for information that jumps out as “relevant,” taking in the included GIFs or images instantaneously as you move past. You might listen to a track posted on SoundCloud in much the same way, keeping your ears open for sonic signifiers earmarked as “interesting,” engaging your unconscious with the sounds while keeping your conscious mind focused elsewhere. In the soft-focus style of media consumption, one treats every piece of media as if it were merely a fraction of a larger dialogue, which it is your overall goal to comprehend. Every aesthetic gesture you notice can be thought of as engaged in play with the aesthetic gestures of all media surrounding it.

Rather than decrying corporately produced materials as somehow less authentic than artisanal ones, it recognizes every material good on earth is subject to the same global capitalist economy, and so no form is less authentic or inherently “unique” than another — we are all equal amounts the same.

This is where things get weird. Is hyperassimilation an environmentally necessary adaptation to the seamless, perpetual shifting of information in our era, or is it just a case of referential mania? Observe the development of aesthetic trends too closely, and it may begin to feel like your mind is the conduit for some kind of message written in the trends, a God in the machine. Predicting the next lurch of the aesthetic contraption has become an increasingly real-time phenomenon, so much so it’s even been classified as a type of athletics by some of today’s media theorists. I’m sure there are some who would say that as we gravitate toward a more competitive relational aesthetics, we will be losing the deeply personal nature of art that drew so many to the Elliott Smiths and Bright Eyes’ before the shift to a seamless digital media continuum. For my part, I would argue even if we are just trading in one delusion for another — the myth of the songwriter’s narrative truth for the myth of aesthetic cohesion in mass culture — it’s a necessary lie that allows us to continue operating as if our conversation hasn’t devolved into unintelligible empty signifiers. Or, put more simply, to keep on living.

People around my age, too old to be digital natives and too young to be able to sustain a technological abstinence in today’s world, are burdened with the weight of memory — even as the networked mind appears brilliant and sleek to me, like a diamond, its gradual revelation gives way to an emptiness in the pit of my stomach. Because the shift to online life happened during the existence of my peers and I, the occurrence has become inseparably tied in our memories to the more universal happening of simply growing up. The nostalgic disconnect from early childhood so many through the ages have addressed has, for millennials, an eerily finite standard of measurement.

Whether or not the move to online existence inspires nostalgia, anxiety, or excitement, it’s happening and will continue to happen. As I see it, millennials are faced with a choice: we can refuse to participate and become gradually more alienated from the modern conception of what it means to live on Earth, or we can cut our losses and go along for the ride, keeping the illusion of individuality that we can still feel from our youth as a potent reminder of how a shift in technology can reshape the meaning of existence mid-existence — this happened to millennials in our early teen years, and our consciousness is still working overtime trying to catch up. With my own sanity in mind, I look to the future with a soft focus, the horizon mutable, like an eyelid that droops at the close of day, anticipating the gentle fallacy of its own gaze.