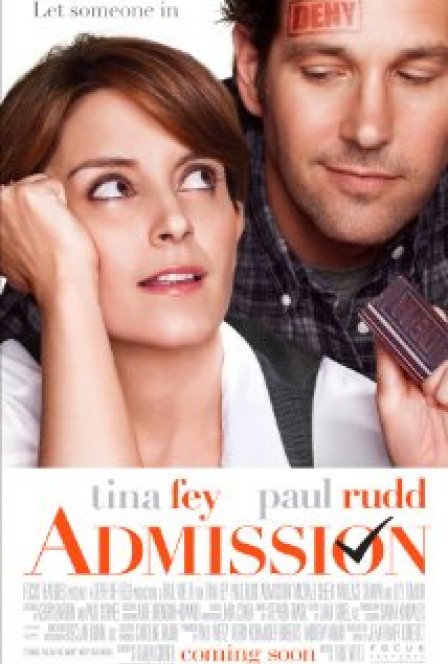

There’s a genre mathematics at work in Paul Weitz’s humdrum new comedy Admission. Two charming known quantities play a mismatched pair that inevitably grow from stern opposition into a complementary pair, a couple who shed their hangups by discovering one another. Tina Fey plays Portia, a tightwad admissions officer at Princeton; Portia lives with an English professor (Michael Sheen) who treats her (explicitly, at one point) like a loyal dog. Paul Rudd’s character, John, runs an alternative education high school in rural New Hampshire; he’s a wealthy heir who’s trying to save the earth but can’t acknowledge that his life needs grounding and structure. John’s eager to get a student of his — Jeremiah (Nat Wolff), an autodidact with lousy grades — accepted into Princeton, and so invites Portia to visit the school.

Admission leans hard on its actors to make something out of an ill-formed story. Fey’s character is uptight and mundane by default, but the film relies on the notion that she had a kid sometime during college and gave the baby up for adoption — John’s gifted little buddy might be her son. Portia’s adult sternness is ostensibly a reaction to her mother (Lily Tomlin), an independent feminist living in the woods. Portia’s mom claims to have seduced a man on a train in order to get pregnant without having to deal with her child’s father, and so Portia fashions a life out of her reaction to this unmoored way of being. Admission begins to ask too much when it comes to these details; Portia’s evolution from independent child to accidental mother to severely normal adult to expressive liberated woman seems more far-fetched than anyone could expect from what seems at first like a simple mainstream comedy. That Portia is also expected to be heartbroken and bitter around her ex while fiercely competitive at a job she both values and deeply abhors causes Admission to become overstuffed; in the end there are too many details to find any one misery particularly funny, or even engaging.

Portia sets about trying to get Jeremiah admitted to Princeton, but knows early on it’s probably too much of a long shot. The film reiterates constantly that the criteria for admission to elite universities is absurd, though Admission does little to either condemn or champion these notion of exclusion and qualification. That high school students are asked to make obscene demands of their intellect and devotion when considering higher education isn’t what Admission is interested in; it just wants to use hardworking students for comic fodder. Which is fine, but it doesn’t make clear why the hell a student as clever and independent as Jeremiah would ever want to go to a place as structured and sad-seeming as Princeton in the first place. Eventually, Portia defies the boss whose job she covets (Wallace Shawn) in her efforts to secure Jeremiah a spot at the school. John (Rudd’s character) discovers he can’t globetrot anymore (he adopted a kid of his own on one of his travels), and with Portia jobless and John fixed in place, the two of them decide to take a chance on each other and on love, etc.

Admission fails because it over-complicates a story in order to evade its own predictability. Fey and Rudd come prepackaged with charm and effortless humor, but Karen Croner’s script (dredged from a novel by Jean Hanff Korelitz) doesn’t give two of the most playful actors around anything to play with. Even the satellites — Tomlin, Shawn, and Sheen — can’t help but be smart and hilarious, but Weitz leaves them stifled and one-dimensional. The weird incongruities and directorial guesswork stand out, as when Tomlin — a recluse in the woods — goes to work on her fixed gear, or when Rudd enlists Fey to help deliver a calf; these become embarrassing, sad moments in a shoddy film. Admission ends with a series of bitter reveals, dark moments that show where the film’s heart might have lain. These revelations are sloughed off at the film’s close, undercut by two acts of saccharine preamble and voiceover that rarely offer entertainment, let alone humor.