Wuxia films have a long history in Chinese and Taiwanese cinema and as established by the genre’s standards in the 1960s (which themselves were of course built upon over 2000 years of wuxia literary tradition) by the Shaw Brothers and King Hu, the hero (wuxia literally translates as “armed” or “martial hero”) was always a character of action, fighting against past transgressions or oppressive military force — the blade a corrective device used to slice and dice one’s way towards a restoration of justice, honor, and peace. Since Wong Kar-wai’s Ashes of Time brought a more fragmented arthouse mentality to the wuxia film — and the genre’s more recent boom came about with the popularity of Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, a Hollywood love story masked as wuxia film — the genre has become even more malleable and unpredictable than it was in its heyday during the 60s and 70s. Yet, in 2007, when it was announced that Hou Hsiao-hsien, whose glacially-paced cinema is diametrically opposed to nearly the entirety of action cinema, would begin working on a wuxia film, The Assassin, one couldn’t help wonder what bizarre alchemy would result from such an unlikely pairing.

In the eight years since Hou’s previous film, The Flight of the Red Balloon, the longest stretch between films in his entire career, there were numerous production delays, not unlike Wong Kar-Wai’s most recent wuxia-epic The Grandmaster, that led to speculation that The Assassin may have grown to proportions that Hou couldn’t control. And while it was Hou’s largest budget at $15,000,000, and nearly 500,000 feet of 35mm film was shot, The Assassin ultimately ended up being just what everyone should have expected: very much a Hou Hsiao-hsien film, full of the most minute of historical and set design details, his signature slow-gliding camera, extended, long shots, elliptical editing, and a pacing that creates a unique feeling of time and history unfolding like only his films can. Like Hou’s other historical dramas, Flowers of Shanghai, The Puppetmaster, and the middle segment of Three Times, there is an acute specificity of time and place and a melding of the personal and political that allow his oft-emotionally distant style to accrue a power and meaning that is transportive as well as emotionally and intellectually rewarding.

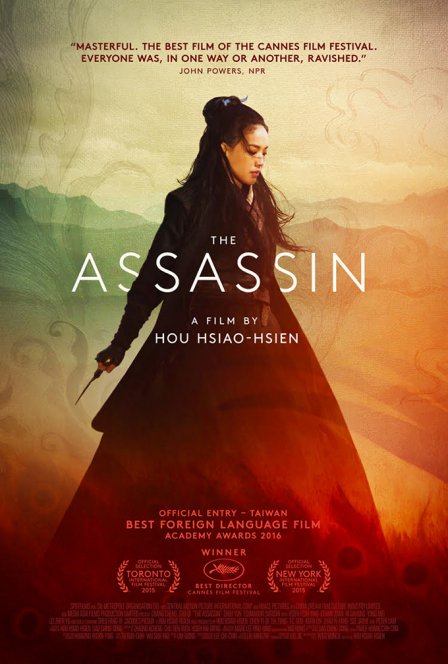

The Assassin is loosely based on the 9th Century short story “Nie Yinniang” by Xing Pei, with Qi Shu playing the titular female protagonist with steely cold precision. Hou uses the story’s mysterious, almost ghostly Nie Yinniang to create a fully formed yet unknowable and complex character whose inaction, rather than actions, defines her. Turning the wuxia genre inside out from being defined by its protagonist’s aggressively action-oriented courage into one defined by her contemplative, indecisive inaction, The Assassin is one of the most elusive, mysterious and meditative wuxia films ever made. As should be expected, it is more of an arthouse film than a genre film, yet Hou doesn’t completely abandon story or structure, although he does stretch both to a point almost beyond recognition. The seemingly simple central story begins with Yinniang choosing to spare the life of a target because she discovered him with his newborn child. Her master, a warrior nun who took her away from her home in the Weibo province when she was 10 and raised her as an assassin ever since, comments that her skill is unmatched but that her emotions lack discipline and sends her back to Weibo to kill the governor, Tian Ji’An, who also happens to be her cousin to whom she was at one time promised.

Her presence upon her return to Weibo is spectral as she remains hidden in the shadows or behind curtains, hesitating to kill Tian Ji’An, yet repeatedly making her presence known with brief battles before disappearing without a trace. Some have interpreted the film through a feminist lens since Yinniang’s actions are in defiance of a task set before her by the emperor and a government of men, but Hou seems more interested in the broader ways men and women wield their power — the men are direct and decisive while the women quietly assume their role, working their angles in secret. But focusing on plot and political perspective in a film like this is essentially a zero-sum game. Hou, working again with long time cinematographer Mark Lee Ping Bin, is more concerned with capturing the impressions and feel of the era, his gliding camera drifting delicately about the transparent curtains that line nearly every room, pausing behind candlelight merely to delight in the myriad ways the fractured light bounces off the gorgeous fabrics or capturing the sound of wind running through the forest trees or an open door. The ambiance of the environment and the pauses between action scenes where characters relax or discuss strategies in hushed conversations is where the film gathers its true meaning. It is a reflection on time in another place, yet the specificity of its period details, both in the set design and in the leisure activities and political proceedings that are shown ground it in a reality that is multifaceted and remarkably convincing.

Much like the main character, it is during the silences and long stretches of inaction that The Assassin strikes the hardest. As the plot dissolves from concrete to impressionistic, character’s motivations and even identities become unclear (I wager that few people would know that the gold-masked assassin who shows up to fight Yinniang on two occasions was actually the Jiaxin, the nun who taught her), the poetry of Hou’s images comes to the forefront, not merely as eye candy, but as a reflection of a time and place that is alien to us, history rendered realistically in all its enigmatic inaccessibility. Hou distills the plot to its very essence, perhaps even beyond it, refusing to connect the dots or help explain the meaning behind every scene, yet nothing feels perfunctory or out of place. Its message is delivered clearly enough through Yinniang, but its crowning achievement is its transformation of the wuxia into an elliptical, labyrinthine meditation on existence in 9th Century China. It’s uncanny ability to be meticulously precise in some aspects, yet distant and mysterious in others make it a unique achievement and exactly the kind of film that could only be made by a master like Hou Hsaio-hsien.