After a nine-year absence, nostalgia merchant Lawrence Kasdan has returned with Darling Companion, henceforth to be known as the canine travesty. This sense of profound disappointment comes not from lofty expectations, but from a place of worthy regard. Kasdan has an award-winning résumé as a screenwriter and director, and his achievements are incontestable. Before settling down with the Baby Boomers in The Big Chill, he penned the sequels in the original Star Wars trilogy as well as Raiders of the Lost Ark. And he continued to be a player throughout the 1990s, though critical reception to his work steadily declined and finally bottomed out with the abysmal Dreamcatcher. But in the accelerated decade that recently passed, he either moved into semi-retirement or had a debilitating case of writer’s block, because his lack of fluency is immediately apparent. Kasdan teamed with his wife to compose Darling Companion, and while it may have enabled him to finish the project, it would be a stretch to argue that it was the right decision.

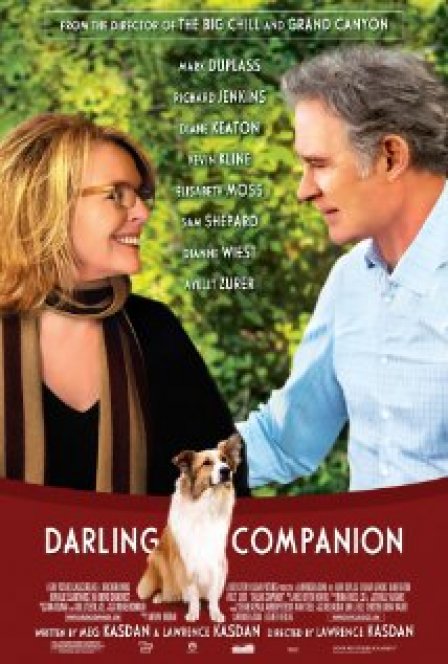

Darling Companion is the first film financed by Kasdan’s production company, and he’s on record stating that the story is profoundly personal or essentially drawn from events in his own life. The reminiscence begins when Beth Winter (Diane Keaton) and her daughter Grace (Elizabeth Moss) spot an abandoned mutt on the side of a snowbound Denver highway. After some hesitation and growling, they pull a tie around the dog’s neck and drive him to the vet, where Grace promptly falls in love with its caretaker. Against the wishes of Beth’s husband Joseph (Kevin Kline), they foster the dog and name him Freeway. As Freeway becomes a fixture in the Winter household, Grace’s romance blossoms into engagement, culminating with a wedding at their summer home in the picturesque Rocky Mountains. The wedding is the catalyst for everything that follows. It’s also where we’re introduced to the Winter clan — a cast of broadly sketched characters who get roped into searching for Freeway when he runs away from Joseph.

So here we have a common problem and a horde of talent to solve it. The setup is Altmanesque, but the ensuing narratives are drivel. Though it feels sterile and staged, Beth and Joseph’s embattled relationship is the principal thread, while the romantic lives of others are revealed through intimate yet instantly forgettable conversations. Joseph’s sister Penny (Diane Wiest) and her entrepreneurial boyfriend Russell (Richard Jenkins) break the news that they want to use Penny’s retirement fund to underwrite an authentic English pub in Omaha, while Penny’s son Bryan (Mark Duplass) is tempted to cheat on his absent girlfriend with Carmen (Ayelet Zurer), a soothsaying Gypsy. The psychic Gypsy bit is by far the most egregious aspect of this mess. Zurer’s character is painted as an unflattering stereotype with “visions” integral to their journey — it’s borderline camp, but there’s nothing to indicate whether it’s an in-joke or not. Carmen acts as a guide for the search party, sending them to her divined destinations, and we’re privy to their musings on the trials of existence. Looming over their humanist discourse is the glaring truth that most of their complaints could be pegged as “White People Problems.”

This cultural limitation could also be found in Kasdan’s past works, but with The Big Chill, he captured the zeitgeist and in later efforts had a tendency to be more embracing. With Darling Companion, he continues to reckon with the turmoil of aging and parenthood, but the substance has been diluted and feels uninspired. In a blatant attempt to give the film temporal meaning, the Winters carry iPhones and mourn the death of their battery power. But we all know that’s just a mundane aspect of modernity: addressing it outright only implies that the writer is aware of how the world has changed since the last time he dug into these matters. The real issue is that the conversations of his fading generation are wearisome and ordinary. And that doesn’t bode well for the future.

There’s a strange parallel between these characters’ bloated words and the vacuous bedroom banter of some of the less developed mumblecore films. Maybe this suggests that the propensity for hollow introspection is circular, but if you’re going to spend an hour hiking in the woods, there should either be riveting dialogue or some enlightening ego exploration. In this trying expedition, they hardly scratch the surface of either.