About a week ago, I saw my old car, a 1999 Oldsmobile Eighty Eight LS, out in the wild. My name for her was “Goldie Hawn the Car” and she was a grand vessel, a majestic beast of a grandma car. I only got to be with her for a couple years (previous owners: my mom, and some living stereotype of the “little old lady who only drives to church on Sunday”), but we shared many late nights and even a cross-country adventure together. I loved that car. Every paint chip beauty mark, every sign of strain on her leather seats, only endeared me to her more. Once my girlfriend’s newer, more efficient car made its way out here from Michigan, though, keeping Goldie seemed a bit self-indulgent. Besides, she’s just a car, right? Besides, I had to pay rent, right?

Right. Still, when I saw her parked on the street, the fist-sized paint chip on the hood still slowly expanding, dirtier than I would have ever let her get, it took all my will not to dash over to her. I wanted to run my fingers along the hood, take a rag and wipe off some of the dirt, and say “thank you for everything. I’m sorry I abandoned you.” It was not unlike seeing an ex-girlfriend who has fallen from grace a little, maybe one who’s taken to drinking a lot more than she ever did before.

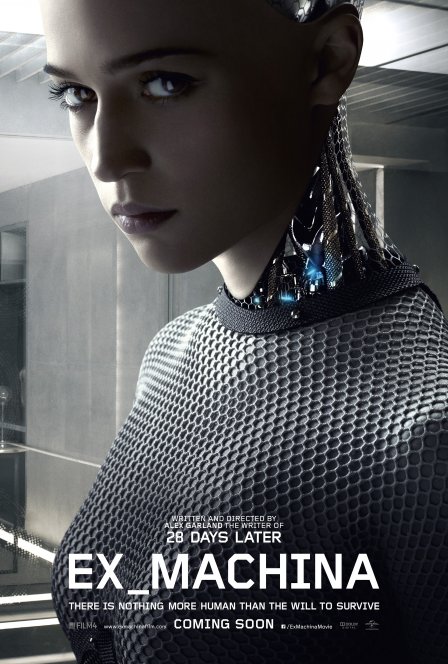

With this in mind, I would contend that Alex Garland’s new film Ex Machina reaches further than is necessary to make its point. We already love machines as if they were our children; we (usually) don’t want to have sex with those machines, sure, but a robot needn’t have artificial intelligence and look like Alicia Vikander for us to get attached.

Then again, maybe that human propensity for loving things which cannot love us back is exactly what makes Ex Machina’s primary conceit (basically, the classic sci-fi trope of humankind sowing the seeds of its own undoing via irresponsible use of technology) gripping and believable. The film asks many of the same questions about humanity’s relationship to technology as Her (TMT Review), but where Spike Jonze approached those questions from the perspective of the schlubby post-AI consumer, Garland explores the ethics of AI from the point of creation. The result sometimes plays out as rote science fiction, with its stiff expository dialogue and standard thriller structure, but the way Ex Machina charges through its intended theses (and some, I suspect, which are unintended) makes such quibbling concerns irrelevant.

That, and there are just fucking kicks here. The special effects are aces; the soundtrack is a throbbing scorcher akin to that of Under the Skin or It Follows. Oscar Isaac, portraying the insufferable billionaire tech-bro savant Nathan, utilizes his skill for magnetic douchebaggery (witnessed previously in Inside Llewyn Davis) to new ends: as Nathan, Isaac is still playing pathetic, but this time he has the intellectual, emotional, and economic means to successfully overcompensate. The question, naturally, is whether he might also have the human decency to care how his hunger for glory may effect the rest of humanity. Disregarding such boring concerns, Nathan secretly brings in his employee Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson, as nerdily befuddled here as in last year’s Frank) to provide a Turing Test for his miracle invention, a babe-shaped robot which he believes to be the first instance of true Artificial Intelligence. Caleb is extremely bright, but he is in way over his head from the moment the robot, Ava (Vikander), walks into view. The rest of the movie documents Caleb’s struggle with the morality, semantics, and plausibility of legitimately falling in love with a sexy robot.

This could have gone pretty wrong (and it has, many times), but Ex Machina pursues its subject matter with care, plenty of satisfying twists and turns, and even genuine philosophical weight. As a film, it’s far less formally challenging than some of its peers, but maybe that’s okay: as with Philip K. Dick, the craft isn’t really the thing here so much as the central idea.

Besides, sometimes the direct approach is the most effective. I left Ex Machina awake to my surroundings, keenly aware of the film’s real-world implications. More acutely than ever, I sensed that anyone around me could secretly be a robot; even if it isn’t the case yet, it could certainly happen at any time with or without our knowledge. Still dizzied by Ex Machina’s plot pivots and faced with downtown streets teeming with people staring down at their mobile devices, I was struck most brutally by just how little fucking difference that terrifying circumstance would probably make.