In life, Vivian Maier was elusive. And in death — despite the best efforts of John Maloof — she remains so. Maloof is an earnest young man whose relationship with Maier began in 2007, when he won a trove of her negatives at a local auction. When he discovered that he had actually purchased the work of an unknown but accomplished street photographer, he set out to find Maier, only to discover that she had recently passed away. In Finding Vivian Maier, Maloof tries to piece together her life. It’s an unsettling journey with an unsatisfying conclusion, if only because it’s impossible to fully portray a life without the woman who lived it.

When Maloof first looked at his auction loot, he thought Maier’s pictures were terrific. But he couldn’t find any information about her, aside from her obituary, and the photography novice didn’t trust his own eye. So turned to the Internet (of course). Enthusiastic responses on Flickr confirmed his hunch. Maloof quickly — and legitimately — acquired as many of her possessions as he could. He bought the other boxes sold at auction from their winning bidders. And some basic sleuthing led him to a storage unit, from which he rescued thousands of negatives and rolls of undeveloped film.

Maloof’s discovery also sparked a worldwide news story. After all, the basics are juicy human-interest-headline bait: Maier worked as a nanny, primarily in Chicago, but died never having shown her work, which is on par with the greats of street photography. She was an artist hiding in plain sight, only to be celebrated posthumously. People ate it up. And then they moved on.

Except Maloof. “My mission is to put Vivian in the history books,” Maloof tells one broadcast news reporter.

After rehashing this background story, this documentary picks up where the headlines left off. Overwhelmed by the sheer scale of his discovery and convinced of its inherent artistic value, Maloof first attempts to give the photos permanence and value through the expected channels: museums. But they’re not interested.

So he continues plugging away at the monumental task of organizing and archiving her work by himself. But he becomes obsessed with more than Maier’s photos, telling us, “You always want to know, who is behind the work?” He begins reconstructing Maier’s life from her artifacts, and there’s plenty of material to work with. In simple and symmetrical Andersonian shots, we see Maloof’s treasure: dozens of income tax checks laid out like wafer-thin bricks; audio tapes of her own thoughts and interviews with locals about current events; a veritable mosaic of colorful costume jewelry; bus passes; buttons; film reels; and dozens upon dozens of photo envelopes.

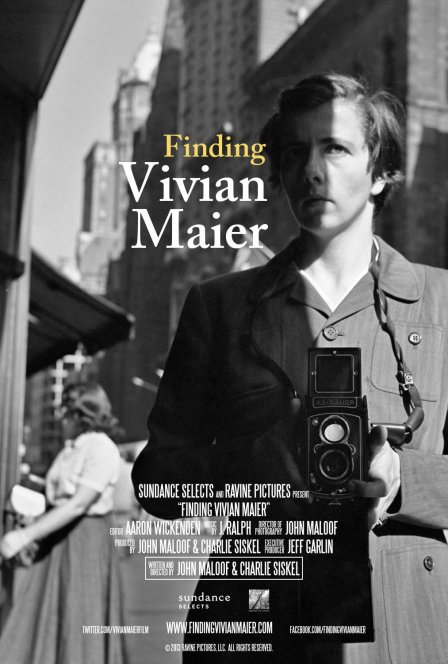

Maloof gathers an impressive group of interviewees. Photographers Joel Meyerowitz and Mary Ellen Mark lend credibility to Maier’s art — and the images themselves are certainly stunning. Whether snapping a stoic portrait of one of her young charges or a surreptitious shot of an elderly couple asleep on a railcar, Maier’s photos seem to simultaneously burrow straight to the heart of a moment while telescoping outward to the world beyond the picture’s borders. But mainly, we hear recollections from Maier’s former employers and their children: Maier’s lumbering height, vaguely French accent, and ever-present camera. She was odd, everyone agrees, but fiercely independent. She was also fanatically private.

And therein lies the film’s moral paradox. It seems clear that Maier never would have wanted her life on display, so why reassemble it publicly? Maloof is acutely aware of this dilemma and allows Maier’s acquaintances plenty of room to air the grievances she surely would’ve had. Yet he persists.

At first, I felt that Maloof and co-director Charlie Siskel were pursuing the wrong path. Here is a private woman with a collection of work that stands on its own. Why must we mythologize the artist’s life?

But a 1978 essay by John Berger got me thinking I may have too hastily dismissed their mission. Berger’s essay, “Uses of Photography,” is a response to Susan Sontag’s seminal work, On Photography. He writes about the danger of severing images from their meaning, namely the continuum of time from which they are snatched. “The aim must be to construct a context for a photograph, to construct it with words, to construct it with other photographs, to construct it by its place in an ongoing text of photographs and images,” Berger writes. Context also includes memory, which “is not unilinear at all. Memory works radially, that is to say with an enormous number of associations all leading to the same event.”

And this, in fact, very closely mirrors Maloof and Siskel’s endeavor. The film moves in unpredictable directions, often circling back on itself and its themes: Maier’s quirks, her secrecy, another anecdote, another snippet of remembered dialogue. This kaleidoscope of memories occasionally feels repetitive. (The music, an obvious instrumental score, doesn’t help.) But a hazy image of Maier does emerge.

The film is unsettling and unsatisfying. But these feelings arise precisely because Maier is missing. Without her, we are left only with her artifacts, the flotsam of her of memory washed ashore in her wake.