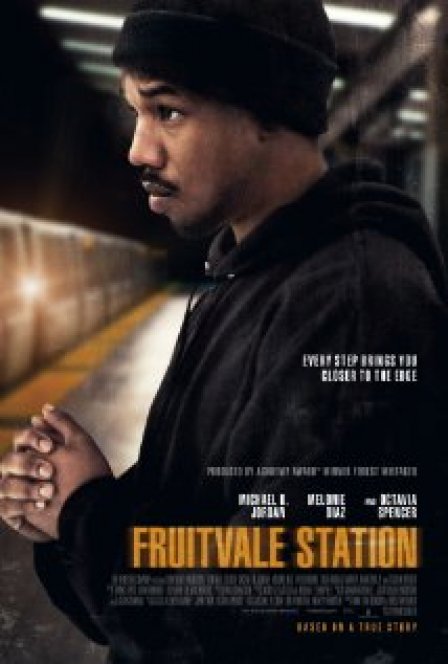

Cops are fucking awful. Or, at least, I struggle to think of a time when the mere presence of police hasn’t prompted me to flinch or whimper. I don’t know anyone in whom cops inspire a sense of security more than a sense of dread. Oscar Grant was killed by a BART Police officer coming home on a crowded train on New Year’s Day 2009. Ryan Coogler, a Bay Area filmmaker who works as a counselor to kids in juvenile hall, chose Oscar’s story as the subject for his first feature film after directing three successful shorts dealing with similarly dark subjects. Fruitvale Station covers the last 24 hours of Oscar’s life, in which he begins haphazardly to reevaluate his choices and start a new path.

Coogler’s approach to storytelling is uncomplicated, and the characters in Fruitvale Station behave pretty much as expected. Oscar (Michael B. Jordan) never betrays any mystery in his expressions; even his lies only serve to more hammily draw his character. Oscar’s daughter, Tatiana (Ariana Neal), does little more than be the cute kid, and unfortunately has an irredeemable exchange wherein she warns her father not to go out on New Year’s Eve, certain something bad is going to happen. These declarative and prophetic moments are Coogler at his least accountable. All over, Fruitvale’s script is weighed down with instances of broadly drawn character development and stock exchanges. Part of this might be out of a sense of loyalty to actual exchanges between real people, but when Oscar argues with his old boss at a grocery store, the dialogue gets thick enough with clichés that it’s hard to focus on whatever emotional heft the scene might have had. The filmmaking itself never gets interesting; Coogler wants only Oscar’s narrative to be visible, and so despite a deep familiarity with Oakland both director and subject never seem to explore the city, referring offhand to locations and punctuating dialogue with local idioms but never showing much sense of place.

Knowing how Oscar’s day ends makes it hard to trust his gestures towards a more stable future. Eventually, he dumps his only source of income — a giant bag of weed — into the ocean and starts to cut his ties with drug dealing altogether, committing at least to his only stated New Year’s resolution. Even as his evening begins, he reveals his unemployment only to his girlfriend, continuing to lie to his family and friends. Coogler communicates only that Oscar wants deeply to be and do good. His friendly interactions with strangers — a girl trying to buy fish for a date and a man trying to find a bathroom for his pregnant wife — demonstrate his casual kindness with a total lack of subtlety. Watching, the audience is never curious about whether Oscar is learning or growing; Coogler’s filmmaking is transparent, with basic arcs. It avoids combustion. Even once Oscar and his friends go out to celebrate, ringing in the new year on a train, the party-like atmosphere feels artificial, even hacky. Coogler wants only to describe a simple day in Oscar’s life, but ends up injecting so much standard-issue character development he risks letting his film become merely a lesson. Oscar himself ultimately would have preferred to stay in on New Year’s Eve, furthering the awkward premonitions that clang around in the script.

What redeems Fruitvale Station somewhat from its technical and narrative flaws is the film’s refusal to ignore Oscar’s faults. Instead, Coogler juxtaposes Oscar’s past (cheated on his girlfriend, fired from his job, pot dealing, time in prison) with elements of Oscar’s basic decency: he calls his mom on her birthday, he’s helpful to strangers, he cares for a dog, he’s filled with unequivocal love for his daughter. Plenty of these positive moments are cloying, even manipulative, but they still underscore basic truths about Oscar: that he’s a confused 22 year old who may well have been on the cusp of becoming a genuinely good person. And then, of course, he gets murdered by a transit cop. The film opens with one of the many available cell phone videos documenting Oscar’s shooting; the whole movie barrels toward the moment this wrong, fucked up thing happens. Coogler doesn’t dwell on the political or social implications of Oscar’s death within the narrative; he wants only to demonstrate his subject’s humanity. As a result of a too-casual approach to deadlines, I happen to be finishing this review in the ugly glow of George Zimmerman’s acquittal. Oscar Grant, like Trayvon Martin, would still be alive if he hadn’t been black, a fact Coogler demonstrates deftly. I’m white as hell — no one needs my thoughts on race or politics. In the aftermath of the Zimmerman ordeal, though, Fruitvale Station obviously becomes a much more urgent film, emphatically relevant despite its clumsier aspects. So much harm is casually done and perpetually forgotten; Coogler has authored a vivid reminder of ongoing brutality, a reminder that could be handled more capably, but one that needs to exist all the same.