When Sergei Eisentstein established cinema’s ability to cut to another image as the basis of film aesthetics, he probably did not envision its role in contemporary comedic cinema as an almost magical means by which the filmmaker relieves the discomfort he or she creates in a scene. Awkwardness between people in real life tends to drag and grind to an unsatisfactory resolution, but awkwardness in film comedy breezes on by with the click of the editor’s mouse. Whereas the Soviet auteur saw the power in film as its ability to compile distinct images in sequence, comedic directors seem to view it as the ability to place jokes revolving around conflict within a scene without lending any significance to the narrative or characters. If this were a throwback to the absurd non-sequiturs of Mel Brooks or early Woody Allen, we might be witnessing a positive trend in comedy’s ability to poke fun at the culture around it. However, as both studio and independent comedies seem to be mired in a misplaced attachment to a highly contrived “realism,” audiences will have to continue to dig their nails into their skin while forcing themselves to smile at the images on the screen until the director and editor mercifully agree to cut to the next scene.

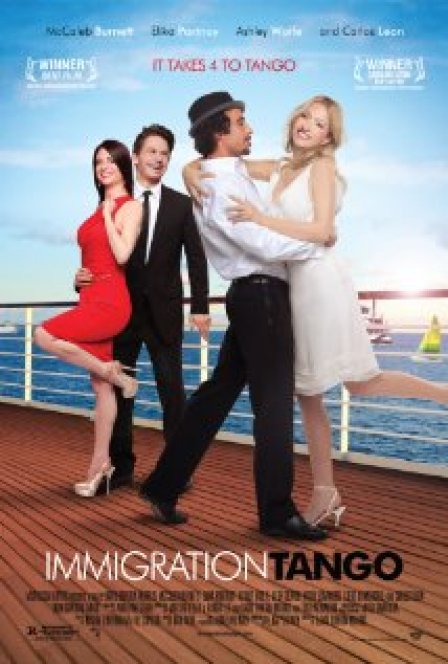

David Burton Morris’ Immigration Tango seeks to update the classic American screwball format to our multicultural modern era. Elena Dubrovnik (Elika Portnoy) and Carlos Sanchez (Carlos Leon) originate from Russia and Colombia respectively, but have made a life together living on a boat docked in a Miami marina. Their best friends Mike White (McCaleb Burnett) and Betty Bristol (Ashley Wolfe) are gringo (in case naming him White wasn’t subtle enough for you) graduate students with a cozy little apartment and comfortable life in the city. When Elena’s visa is set to renew, the four concoct a scheme to fake a marriage between Mike and Elena. The immigration authorities start to investigate, and so the couple must take the plan to the next level and actually switch partners, at least to outward eyes. Mike and Elena, living in the close quarters of Carlos’ boat, begin to develop an attraction and appreciation for one another. Betty soon realizes the dissatisfaction in her own life, while Carlos kind of sits around and plays a caricature of a Latin male.

The dramatic setup Morris creates here naturally lends itself to the layering of awkward situations within awkward situations. If the point were merely to show the tension and discomfort between a group of friends and lovers in a hackneyed situation (remember the film Green Card, not to mention a pretty worn-out joke about foreigners looking for status), then the film succeeds in doing just that. However, Morris never really gives a chance to understand why these people who are so very different are friends in the first place or romantically involved in the second. He provides a tenuous hint that they met while studying at the university, but beyond that, there seems to be very little holding the bond that is tested by this situation. And while this may have been an interesting opportunity to explore the idea that romantic relationships are about adapting to another’s person presence as much as attraction or past experience, the film seems content to show the couples’ lives in a series of montages (thank you once again, Mr. Eisenstein).

The other aspect at play here is the interactions between different cultures in an increasingly connected world. Miami, too, as an international crossroads and perhaps the only major American city whose politics and culture is dominated by an immigrant minority, could have proven an interesting choice had the filmmakers sought to elevate the sociology beyond what they had seen on reruns of Miami Vice (“Hey, remember how that guy Crockett used to live on a boat?” “Yeah, that was cool, let’s use that!”). Morris seems content to rely on pure cultural stereotypes: the repressed WASPs, the sensually liberated Europeans, and the fiery Latinos are all showcased here with very little self-awareness. So when the stock character of the offensive, Anglo father asks Carlos if he’s from Mexico, both comedy and cultural nuance come to a crashing halt.