I am well aware of the unpopularity of my opinion that Frozen River is a steaming pile, that its portrayal of life in poverty does little more than rub the audience’s nose in calculated details like working at a dollar store and having Tang and popcorn for dinner. Its limp thriller story line relied almost solely on our pity for Melissa Leo’s Ray to generate tension, rather than actual thematic weight, narrative economy, or visual inventiveness. In total, the film amounted to little more than a blunt cataloging of these details, calculated to tug at the cockles of our hearts like a bratty kid pulling the ponytail of a girl he likes. And now that I’ve said my piece about one of last year’s most baffling critical faves, I offer you Erick Zonca’s Julia, his first film in a decade, as a corrective.

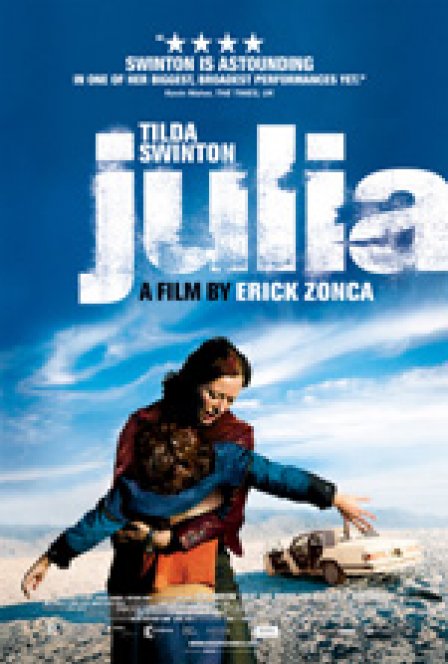

Where Courtney Hunt’s film feels contrived, forced, and pandering, Zonca’s is risky, genuine, and alive. It is a film mature enough to avoid the simplistic liberal back-patting and condescension inherent in Frozen River’s faux-realism, instead challenging us with a bitter, hyperactive alcoholic whose own criminal enterprises are fueled entirely by self-interest and greed. It’s not as focused on the element of poverty as Frozen River, but its thriller mechanics and the nature of its character study of a woman on the outskirts of society make it a fair comparison. That Julia combines a riskier examination of its struggling heroine with a richer, more complex central relationship, in this case between Julia (Tilda Swinton) and Tom (Aidan Gould), the boy she kidnaps, makes for a significantly more substantial and engaging experience.

Julia often walks a thin line between pure thriller and the blackest of black comedy, hitting moments where the tragic and comic intermingle in tender yet uncomfortable limbo and pushing our sympathy for Julia past the limits of reason. And yet, as cruel and (mis-)calculating as Julia is a majority of the time, Tilda Swinton’s mesmerizing, heart-wrenching performance evokes empathy at every turn simply because her character is so genuine: She's not some fictional construct created so that an equally false shot at redemption could magically meet her at the end of the road. Erick Zonca’s loose, freewheeling camerawork is perfectly in tune with Swinton’s every move, keeping us right by her side, forcing us to share her journey and somehow pull for her despite how increasingly ridiculous, desperate, and disastrous her choices are.

The development of Julia and Tom's bond is flawless, as we’re never sure he trusts her completely, and she continues feeding him one line of bullshit after the next, even in the film’s touching and hilarious final line. It is in its most outlandish sequences, as the plot spirals out of control, that Julia and Tom meet in desperation and the two finally become meaningful surrogates, filling in the emotional gaps that had been widening since Julia set her plan in motion. Their connection always remains something of an enigma – his tacit acceptance of her trust even as he doubts her honesty, her eventual compassion for him despite putting him in harm's way for her own benefit – until the very end, when the film’s two emotional planes, the comically absurd and genuinely tragic, collide.

That Swinton, one of cinema's greatest working actresses, plays a raging bitch of an alcoholic already makes Julia more promising than most films. But its array of soulful supporting performances, the mysterious, elliptical editing, and a general air of desperation all combine brilliantly to create an unrelenting, offbeat tension and a despicable character who paradoxically becomes more human as the mess she makes grows. The film has already drawn comparisons to Cassavetes -- particularly since the title itself alludes to his own troubled woman/little boy on the lam film, Gloria, and Julia herself would fit right in with the tortured souls that populate his films’ worlds. Yet Julia is far more anchored in its genre and narrative than anything Cassavetes made. It speaks to this film’s singular nature that it can retain the psychological complexity of a Cassavetes film even during the most nail-bitingly intense sequences.