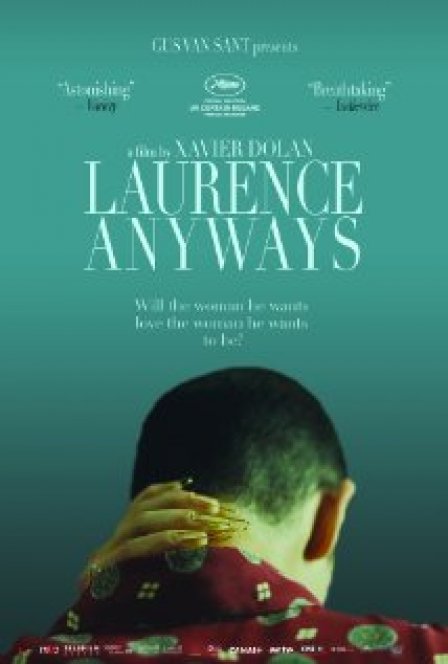

Laurence Anyways is a big movie. Not because it’s nearly three hours long (it is) or because it tackles an extraordinarily difficult subject (it does), but because director Xavier Dolan intended it to be. He wants it to be his Titanic. Judgment over the merits of this inspiration source aside, the film’s ambition is palpable. It’s a big movie, and a success to that end. But further sharpening a description of the artistic voice and intent proves trickier. Buoyed by its scale, Laurence never drags, but also never unifies. Not that it necessarily needs to do so.

The movie is divided distinctly into three acts, each of which could essentially function as its own piece. In the first, we meet the title character, Laurence Alia (Melvil Poupad), a transgender female, living as a male, and working as a literature teacher in Montreal. When girlfriend Frederique (Suzanne Clément) surprises Laurence with a birthday trip to New York City, Laurence snaps, and confesses her disassociation from her assigned sex. Here begins the feature-length question: “How can they make this work?” Both parties embark upon their own impossibly trying personal journeys; Laurence to re-sculpt her life from a lie into a truthful self, at odds with societal norms, and Fred to selflessly support a significant other through a transformation that, in principle, is essential, but in practice, feels unjustly burdensome.

One particularly effective moment occurs when Laurence, in full make up and female dress, arrives in her classroom to teach for the first time after publicly embracing her identity. The camera is in the back of the classroom, yet the telephoto shot places Laurence directly in the center of the dartboard frame, with little distance discernible between teacher and student audience. Above her head hang flags depicting the great thinkers of human history: Socrates, Kant, Descartes. The narrow depth of field flattens the scene into a singular, intimate pedagogical plane. A mind is a mind, whether teacher, student, or source, and after a heavy silence, through which Laurence awaits certain outrage and confusion, a girl in the front row asks for clarification on a homework assignment. The tension isolating the teacher in the dimensional center subsides, and as we track in on her nervous smile, the composition allows Laurence to grow, bolstered by confidence and no longer made to feel so small. Triumphantly, brain trumps body.

Later, walking the halls, we track with Laurence, focusing on the undeniable gaze she attracts from nearly everyone she passes. Some risk a brief glance, while others allow themselves to stare, unabashedly confused, and in some cases disgusted. This is a visual motif that is not only relentlessly revisited, but is chosen to open the film (and, in a roundabout way, close it as well). Almost always set to commanding electro-pop, Dolan clearly intends for this to be a vital sound and image, forcing the viewer to deal with the constant feelings of disapproval and discrimination that a transgendered individual cannot escape in everyday life. It’s just not effectively integrated into the project as a whole, though. It’s a separate element, punctuating the compelling interpersonal drama, and when it happens, one braces not for a development, but for a diversion. Other, more sparingly used patterns are far more effective. The director shows a cleverness for framing, shooting the entire film in a boxy 1.37:1 Academy ratio, claustrophobically mimicking a thematic sense of confinement, and even opting to make that space even smaller during key moments, obscuring our view with a the darkness of an unlit hallway, shearing away all but a thin strip of distant action. Many a shot-reverse conversation transpires with the backs of heads covering faces, expressing misunderstanding and inability to share a whole self.

After the first act ends with Laurence’s firing due to discomfort with her gender identity by her superiors, the second begins with a violent conflict, the echoes of which carry through the middle section of the piece. Arguments explode, relationships are severed, and lives are reduced to shells of what they once were. We arrive at the third act, ready to rebuild. Fred has moved to Trois-Rivières and cultivates a domestic normalcy. Laurence has devoted herself to writing and found success, as well as a new girlfriend, in publishing a book of poetry. Though the characters have found individual stasis, their connections to one another are severed and bleeding, and there’s a distinct craving, in their lives and in in the film’s structure, for resolution. Realistically though, the audience knows that Laurence’s central couple will not live happily ever after. “How can they make this work?” They can’t. As the end draws near, more and more tangible plot points are presented, but their weight decreases with each addition. Much of what we need to know about Laurence and Fred has already been shown to us, and any ratcheting up of story-speed or visual strangeness feels patchwork and disparate. A distraction from the bitter conclusion, already visible in the distance. There’s a certain amount of disappointment built into the DNA of the movies tragic romance, and its not as if Dolan has a responsibility towards a happy ending or a definitive message about what it means to be or be close to a transgendered person. Still, though, people didn’t leave Titanic shrugging their shoulders and sighing.

Individual elements of Laurence Anyways are wildly successful, and even though the film closes on a note of dissatisfaction, the actual final scene is, by itself, engaging and well-presented. The director has no shortage of vision or potent ideas, and the work, as a whole, pulsates with talent. It really didn’t need to be a big movie, though. It didn’t need to be Titanic. It didn’t need to be anything. Largeness, in this respect, is actually confining, and its aspirations betray its capacity for nuance and economy. Dolan says that Titanic “told [him] that cinema was about an epic journey,” and that thought is clear in his most recent work. What’s not clear is why that’s the case.