In a recent New York Times article on the making of the film Love & Mercy, director Bill Pohlad gave some faint praise for the work screenwriter Oren Moverman did on Todd Haynes’s Bob Dyan tone poem I’m Not There. “I thought it went too far,” he told writer Alan Light. “It didn’t really work for me besides being an admirable effort.” It’s a small detail in the grand scheme of making a biopic about Brian Wilson, the enormously talented and often deeply tortured songwriter who helped The Beach Boys reach international stardom. Yet it’s also a telling one, as it reveals just how Pohlad failed in his effort to bring this story to the big screen.

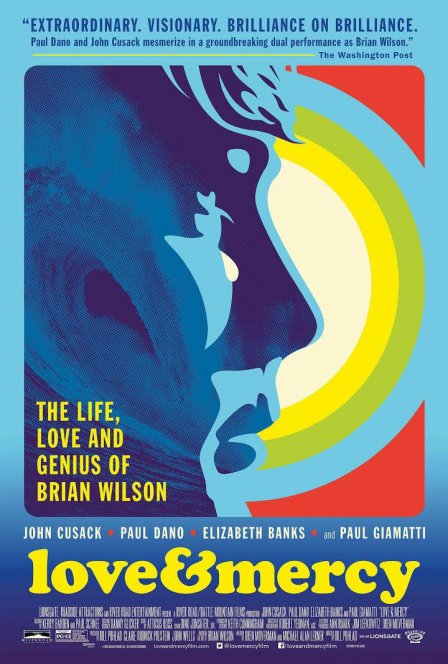

Like I’m Not There, the film uses different actors (Paul Dano and John Cusack) to portray Wilson at different stages of his life and career. But shoehorning this narrative technique into what is otherwise a straightforward story sets the film into choppy waters, bouncing unsteadily between Wilson’s 60s triumphs and 80s nadir. In both cases, the film brings us in media res into these periods of Wilson’s life. The younger version, inspired by The Beatles and his own growing abilities as a songwriter, has freed himself from the iron grip of his father and former manager and is begging off touring with his band so he can concentrate on his magnum opus, Pet Sounds. The older is a shuffling, fearful grownup who has replaced the overbearing parental guidance with that of Dr. Eugene Landy (Paul Giamatti), the psychotherapist who took control of Wilson’s affairs to destructive ends.

Moverman and co-screenwriter Michael Alan Lerner introduce dual forces that lead to the songwriter’s mental collapse and salvation: LSD and a comely car salesman, Melinda Ledbetter (Elizabeth Banks). You can surely connect the dots to see where each of those takes Wilson in the end. But to bring us to his phoenix-like return to the limelight, the script leadens the leads with overly mannered dialogue and boorish exposition made more glaring by Pohlad’s only-passable directorial eye. Were it not for some interesting editing work by Dino Jonaster, who ably captures the thrills of creativity and the frayed edges of Wilson’s consciousness, this might have had all the flair of the stilted made for TV movie versions of The Beach Boys story.

The onus then falls to the actors to ground the wonky dialogue in reality. There, only Dano and Giamatti succeed. The former is as revelatory as ever in bringing out Wilson’s boyish wonder that is slowly taken over by depression, paranoia, and drug-fueled mania. And even when he’s chewing up the scenery, Giamatti plays Landy like a comic book villain, a seductive animal that will snap your hand off if you rub him the wrong way.

They alone might have rescued this movie, but their fine performances just wind up glaring out more brightly when placed against the other two leads. Cusack never seems to find the center of this part, relying instead on his usual bag of vocal and physical tics. He occasionally surprises, though. A scene when Wilson, medicated to the teeth, is reduced to the mentality of a child, begging Landy for some food, is truly heartbreaking. Banks, too, is just… Banks. A fine comedic actress that is turning into an equally good director, she doesn’t feel terribly suited for the drama of this story. Her character’s devotion to Wilson is evident, but her other on-screen emotions feel, like the movie as a whole, rather forced and strained.