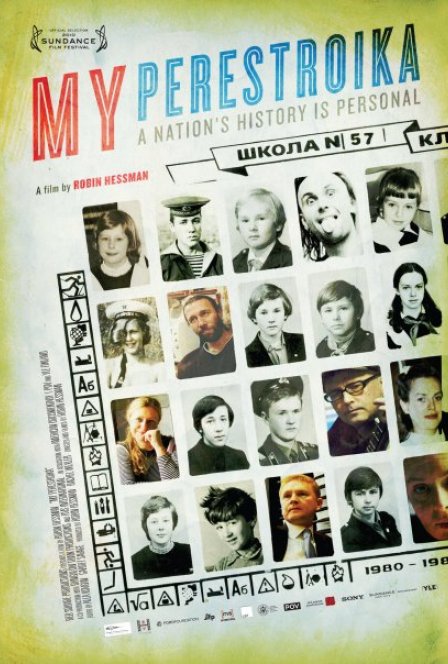

In My Perestroika, filmmaker Robin Hessman follows five friends as their personal transformations ebb and flow with the political currents of the former USSR. The word perestroika literally means reconstruction, a term used by Mikhail Gorbachev as part of the planned reform that indirectly led to the failed 1991 coup and fall of the Iron Curtain. The word is reappropriated here and gets to the core of what the film wants to show us: what happens after the revolution?

Perestroika shows us a variety of options. Borya and Lyuba were politicized at school, taking an active part in the protests during the coup. Settled down in a safe neighborhood with their child, they both now teach history to students, content with their situation, though fire still burns in their eyes. Closest to the couple is Ruslan, the most subversive of the group. When the curtain began to fall, Ruslan started a punk rock band. Divorced with a son, he has split from the group of friends over ideological differences. Andrei, the most successful of the group, owns a chain of expensive men’s clothing stores, fully embracing the capitalist spirit of the West the punk band decries. Olga, referred to as “the prettiest girl in school,” is the most damaged; at times, it’s not clear she’s even aware of the significant changes that happened around her.

As the film progresses, it becomes hard not to feel Olga’s apolitical stance may be for the best. A certain amount of ambivalence is prevalent within every scene of Perestroika: What changes have actually occurred? What was the fight for? Was the old way of living really that bad? These questions are never answered; each character is in a constant state of flux, in between holding on to their ideals, the hope for a new way of life, and a nostalgia for the old world, when everything was supposedly easier.

Director Hessman uses an interesting blend of archival footage of the subjects from the former Soviet state along with contemporary documentary techniques — direct cinema attachment, talking head interviews, etc. The result is a deeply layered mosaic that blends the personal and political in moving ways. This approach allows the secondary characters to jump to the front. Unfortunately, it also slightly pushes the stories of Borya and Lyuba, constructed to be the center of the group, to the background. The emphasis placed on the two ends up feeling forced, and the viewer is often left waiting to get back to the other strands of the narrative.

Where the film fails in construction it more than makes up for in tone. Historical films are often told dryly, with no emotion, or at a rapid-fire pace, creating a sensory overload for the viewer as they try to process all this new information crammed into a tiny space. My Perestroika, however, is a deeply felt, intimate portrait that unravels at its own pace.