With her last film, the revisionist Western Meek’s Cutoff (TMT Review), director Kelly Reichardt torqued her knack for minute observation of character and landscape towards a deliberately confounding and amorphously allegorical territory, seemingly poised on the brink of defining a new style that pushed past the masterful neo-neo-realism of earlier films such as Wendy & Lucy (TMT Review) and into stranger territory. Meek’s Cutoff was an uneven film, but its quietly enormous ambition and first steps towards articulating a new film language made it a landmark nonetheless. Perplexingly, the director appears to have doubled back with her newest film, turning in a thoroughly effective bit of technical genre filmmaking that hones the particulars of her style without expanding the borders of either her own talents or the genre’s.

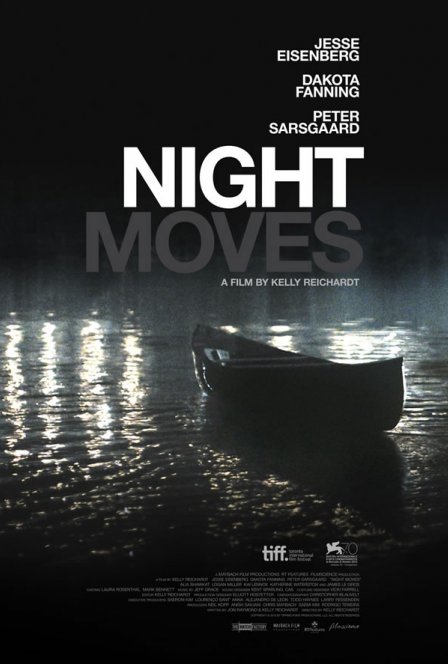

Hinging around a plot by a group of three young environmental activists to blow up a dam, Night Moves begins as piece of process-oriented filmmaking, meticulously attentive to the specifics of individual actions in tight sequence — buying a boat, inconspicuously acquiring fertilizer, mixing explosives — and its focus on the tactile and practical elegantly turns materialist problem-solving into a narrative motor. The precise politics of our young activists are deliberately elided, although Reichardt provides just enough of a character sketch to infuse the situation with some additional tension via an age/education divide, with Jesse Eisenberg’s Josh nervously settling into an intermediary role between his ex-con ex-military brother (Peter Sarsgaard) and the young, wealthy activist played by Dakota Fanning. There’s some underplayed and indistinct business suggesting a romantic tussle, but more attention is paid to the nuances of language and culture than to traditional drama, effectively positioning those elements on the same narrative and aesthetic level of the bits of business involving police avoidance and material acquisition that the film’s first half centers around — all points in a materialist chain.

The lead up and follow through to the dam sequence is a succinct summation of Reichardt’s aesthetic as applied directly and simply to the thriller model, and nearly earns the Rififi comparisons it clearly aims for. It drips with tension and remains admirably centered around the relation between process and spatial dynamics — with the river, woods, and dam placed on equal footing with our characters — but in the aftermath of the explosion the film pivots dramatically to re-center on the interpersonal fallout of our activists’ actions, to depressingly reductive and reactionary ends. An innocent bystander is accidentally killed, and the film morphs into a rehash of standard festival-bait crime and punishment morality play tropes, undercutting itself in spectacular fashion and turning its pressing environmental issues into mere fodder for an unconvincing character drama. Granted, there are scattered glimmers of promise even in the later stages of Night Moves, with some precise renderings of the post-hippie environmental commune on which Eisenberg lives with his family. But there are none of the disorienting elements of Meek’s Cutoff to save the film from falling into easy moral condemnation. Despite some nuanced work from Dakota Fanning, the film falls into a one-note linear progression, with Faninng’s mixture of terror and resolution standing in awkward contrast to Eisenberg as he progresses from bristling, nervous energy towards uninteresting, glowering male angst.

It’s in the film’s later stages that Reichardt’s elision of political context inverts its function, the lack of specificity turning her characters into stand-ins for direct action in general. Culminating in a forced bit of extreme violence, the newfound emphasis on character in a space largely free of visible external forces results in an echo chamber drama, subverting any larger politics to an indistinct mire of handwringing — all second-guessing and lashing out and accidental destruction on the part of the activists without an interrogation of the social structures that produce these results. If even a comparatively rote and tame documentary on the same subject (such as When A Tree Falls: The Story of the Earth Liberation Front) can better illuminate how American structures of policing and corporate capitalism work in sick and symbiotic unity to deliberately corrupt activist work, while avoiding a dismissal of direct action as character flaw, it’s deeply sad that a filmmaker as talented as Reichardt can’t at least pull off the same, especially at a moment when even relatively conservative US governmental climate change groups have been forced to confirm that yes, we are all fucked. Reichardt’s technical chops are as strong as ever, but the constricted structure of the thriller model appears to have constricted her vision and reach as well.