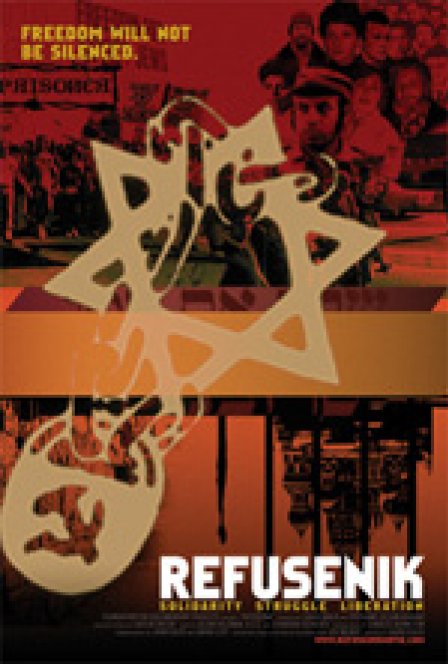

Political activism has played an important role in American history. While the dangers of self-satisfaction always exist within movements that loudly declare their own righteousness, it's hard to deny the impact that a protest can carry. The difference between activism that effects real change and movements that seem merely self-aggrandizing may only reveal itself in hindsight -- our current assemblies on Iraq, Tibet, and Darfur will ultimately be judged against political history, cultural memory, and historical revisionism. Laura Bialis’ film Refusenik privileges these fond recollections over political realities. It is a history of activism that operates within the retrospection of self-love and glorifies the movement over the meaning behind it.

Refusenik documents the primarily American movement that protested the Soviet Union's oppressive treatment of Jews before the fall of communism in 1989. The film moves chronologically, but ploddingly, through the end of Josef Stalin’s reign, the flashpoint of Israel’s Six-Day War in 1967, the dark hours of the 1970s, and right to the end of the Soviet Union. After the unlikely Israeli victory in the Six-Day War, a conflict with the Arab states of Egypt, Jordan, and Syria (among other sympathetic groups in Algeria, Iraq, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia) born out of the rising tensions of a border dispute and the presence of the Jewish state, many Jews felt compelled to emigrate to Jerusalem. But to request an exit visa in the paranoid Soviet state often meant being labeled a traitor. Jews were blacklisted and forced to quit work, placing them in limbo in a place where unemployment was not an option.

The complexity of the situation is rarely properly contextualized in Bialis’ film. Refusenik is blessed with truly wonderful archival footage and comprehensive interviews of the era’s major players, but the filmmaker’s attempt at rendering the world in which Jews were then living seems incomplete and one-sided. We never fully understand the conditions of oppression in the Soviet Union for the Jewish community. We are given only enough to realize that the Jews were being persecuted. Beyond that, there is no attempt to probe into or explain the motivations or psychology of the Soviet government. The film seems to quickly say that Stalin and the communist regime were ruthless, as if it is simply understood that Soviet Russia was evil and no more explanation is necessary.

The story of one of the most recognizable Jewish dissidents, Natan Sharansky, is given a thorough introduction, transitioning from his recounts of life as a refusenik, a man in limbo, to his wife’s international efforts to free him. The archival footage is well-placed and quite effective. The sheer amount of documentation displays the full impact of Sharansky's predicament on his emotionally strained wife, portraying a different kind of victim of Soviet oppression. But while the buildup is well-executed, the payoff is wasted. Suddenly, the Berlin Wall is knocked down and Sharansky is on his way to Israel. The inevitability of history, not the student movement, freed the famous refusenik, but the film romanticizes the story, claiming that only the hope and naiveté of young people could bring down the Soviet Union. This rushed conclusion interrupts the documentary's narrative, artificially solving "the problem" and undermining everything the film worked hard to establish.

The film betrays even its value as a self-congratulatory piece, erring toward a one-note message for today’s youth: "You can make a difference." Perhaps, but there is a reason the protest movement of Vietnam is revered over the Soviet Jew movement. History moves at its own pace, and Communist Russia was falling for a host of factors, not simply and conditionally at the feet of a student movement. Bialis’ film is a bit of a stretch, and it leaves us wondering if she is making a movie about this 30-year, Soviet history or about America’s political climate today in Iraq and its international role with China and Tibet. One can inform the other, of course, but this film's shoddiness does a disservice to both.

Refusenik suffers from a lack of tension, partly due to a lack of explored villainy, and partly because it focuses so heavily on the American protest movement. It's perfectly acceptable to emphasize the protests, but it then feels like a combination of educational documentary and a chronology for the protesters' reunion, failing to convince us of why the dissidence was needed in the first place. The film becomes an empty and self-referential pat on the back to the protesters, not the Soviet Jews, and simply including footage of Natan Sharansky and his peers won't fool anyone.