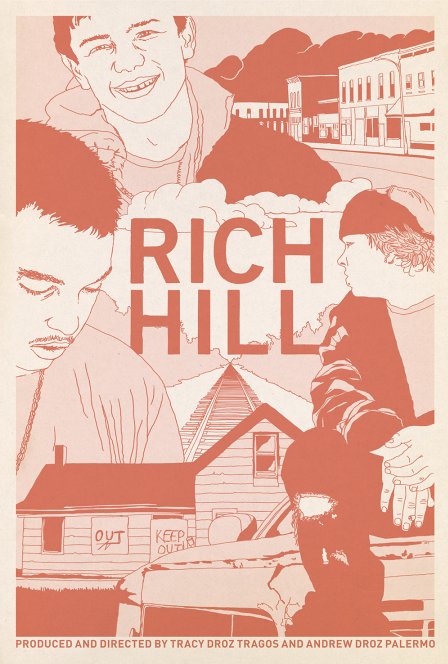

A film grossly at odds with its good intentions, Tracy Droz Tragos and Andrew Droz Palermo’s Rich Hill means to expose the challenges of life in poverty. It follows three teenagers, from one Fourth of July to the next, in the small, titular Missouri town. At the outset, Rich Hill’s town center is briefly transformed into a colorful, patriotic emblem of Americana. The film’s three subjects wander through it, never to meet. In the mode of some recent, impressionistic documentaries, the footage of fireworks and carnival rides is set to a wan ambient score. It operates in the register of an early David Gordon Green film, but this tone can’t withstand Rich Hill’s exhaustive, repetitive parade of degradation.

The teens Tragos and Palermo trail — Andrew, 14; Harley, 15; Appachey, 13 — introduce themselves in stark tones. Andrew’s “We’re not trash, we’re good people” cuts to Harley’s “Anything can trigger me,” yielding to Appachey’s “People expect me to do good things and have a better future… I don’t know what to do anymore.” Edits briefly contrast a town where there might be some happiness — the mid-sections of clapping cheerleaders, bursting with energy — with one that progress and optimism has bypassed: we see a derelict downtown, a tractor dragging a sad tree, and a shock cut to fly tape hanging from a ceiling. This is the side of Rich Hill where we spend the following ninety minutes.

Tragos and Palermo’s subjects, likewise, seem designed to convey some editorial balance, but they’re freighted with hopelessness. Andrew — handsome, athletic, pious, and caring — is our beacon of light, exhibiting a deep tenderness toward his narcoleptic mother and wanderlusting father. His family moves multiple times over the course of the film, running out of money and relocating in hopes of a steady-enough stream of odd jobs. Harley and Appachey, meanwhile, are similar in attitude and temperament: both struggle to withstand days in school and smoke a lot of cigarettes (Appachey lights one on a toaster when he’s introduced), and both suffer from un- or mistreated neurological or behavioral conditions. As each of them flirt with becoming wards of the state, their modest differences are tragic but complementary: Harley’s home is clean, while Appachey’s is filthy and rarely framed without a Pepsi logo in sight; Appachey’s forthright mother is overburdened with work and her other children, as Harley is looked after by his grandmother while his mom serves a jail sentence.

Rich Hill’s use of multiple subjects (not to mention its title) can only indicate ambitions towards a comprehensive — or at least multifaceted — portrait of lower-class, Midwestern struggle, but the film is largely content to inhabit its own, frustratingly hermetic bubble. The film’s reluctance to appoint blame, or to even portray some of the external circumstances that have befallen these families, eventually feels like an abdication of responsibility rather than an aesthetically defensible choice. There’s little sense of life as it’s lived in Rich Hill, just a series of increasingly tough doses of bad news. (The late reveal of the circumstances surrounding Harley’s mother’s imprisonment — however faithful to the film’s chronology — is particularly cheap, and emblematic of Tragos and Palermo’s shallow intentions.) Other “impressionistic,” “beautiful” documentaries (notably Michael Palmieri and Donal Mosher’s great 2009 film, October Country) have weaved broader social tapestries in more intimate circumstances. Rich Hill’s nods to beauty — Appachey breaking through a frozen puddle with his skateboard, admiring the art his destruction has created; self-conscious shifts of focus in exterior settings — are the rote habits of the film’s subgenre. Only one striking scene, a telling interview with Appachey’s mother conducted through a haze of cigarette smoke as sunlight peers through the blinds, seems faithful to the film’s bleak aspirations. Whether or not Tragos and Palmero mean to portray a town, the final impression of this woefully miscalculated film is that its directors managed to find the three most unfortunate families in it.