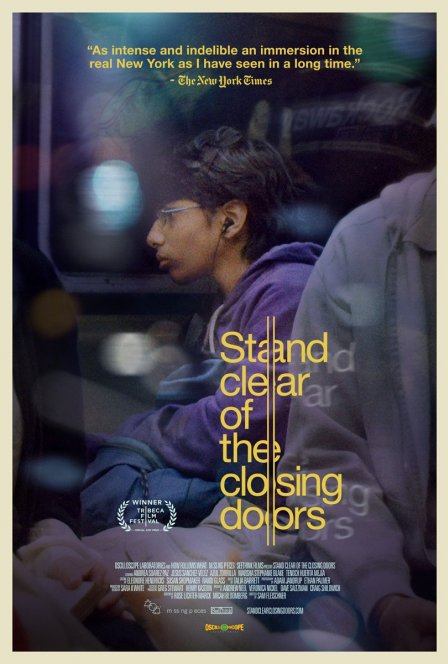

New York, even for devotees, can be an overwhelming place. And for more vulnerable residents, the city can sometimes swell to unmanageable proportions. In Stand Clear of the Closing Doors we watch as a family cleaves, their narrative strands tearing free of each other like unraveled DNA. In both stories, the characters struggle with ever-mounting challenges. For Ricky, a young teenager with Asperger’s who goes on a multi-day journey through the city, the onslaught is sensual: the sights and sounds of New York’s subway enticing and assaulting him in equal measure. On the other side of the East River, in Rockaway Beach, Queens, Ricky’s mother and sister attempt to find him. But their efforts are repeatedly thwarted by factors beyond their control. While their story is more recognizably real, Ricky’s wanderings feel real, and thus, more memorable.

Ricky’s disappearance is set in motion when his sister, Carla (Azul Zorrilla), fails to meet and escort him home after school. Ricky (Jesus Sanchez-Velez), a capable artist obsessed with dragons, spots the mythical creature on a stranger’s sweatshirt. The image ensnares the young teen, drawing him into the labyrinth that is the New York subway system.

With Ricky as our guide, we experience the full spectrum of the subway’s subterranean magic. Ricky’s autism manifests primarily as a sensitivity to stimuli (before his disappearance, he haunts a local shoe store, where his fingers trace the textures of a sneaker and he inhales its musky leather scent). Director Sam Fleischner, cinematographers Adam Jandrup and Ethan Palmer, and sound designers Eli Cohn and Scott Hirsch take full advantage of Ricky’s perspective, depicting his journey in layered abstraction. On a black screen, for example, orbs of light hover in the void like multicolored cells under a microscope; Ricky’s voice mumbles “G train, G train… I train, I train…” over a low rumble and buzzy tone. It’s a beautiful, if disorienting, sequence. Then streaks of white cut through the darkness and you recognize the scene: you’re in the front car of a train and it’s pulling into a station.

Ricky’s journey recalls the sensory overload of last year’s Leviathan (TMT Review) — a rich experience unbound by conventional storytelling. Likewise, Fleischner doesn’t feel obligated to untangle Ricky’s experience. He sees and hears all manner of exchanges: feet tapping, children yelling, musicians playing. And as time passes, and basic survival becomes more pressing, he is also witness to kindness and cruelty. His dreamlike encounters, each portrayed with inventive originality, wash over you, feeling more like reality than any constructed narrative could.

This free-form story runs counter to the linear narrative unfolding in Rockaway Beach. It becomes evident right away that Ricky’s mother, Mariana (Andrea Suarez Paz), can’t act upon her panic. She may want to contact the police, but like many immigrants, she’s wary of official authorities. Ricky’s father — who is away, working for people who haven’t yet paid him — is even more nervous, urging Mariana to keep quiet. Ricky’s school is no help either. A frustrated and unsympathetic administrator adds insult to injury, complaining they can’t adequately meet Ricky’s needs. Amidst this chaos, Mariana continues to show up for work, cleaning the very large home of an idiosyncratic artist.

While Mariana’s story is undoubtedly true for many New Yorkers — and Suarez Paz portrays her role with accomplished naturalism — it somehow feels concocted. Maybe that’s how life feels when every disadvantage begets another, the obstacles so numerous and persistent that they couldn’t possibly all be the plight of one family. And yet they are.

But when Hurricane Sandy appears on the horizon, it feels superfluous, an unnecessary conflict in a story already brimming with them.

Writers Rose Lichter-Marck and Micah Bloomberg couldn’t have predicted that a climax as momentous as Sandy would arrive in the midst of filming. (Nor could they have known that just a year later, Avonte Oquendo, a young autistic boy, would wander away from school and disappear. Posters of his face were plastered on every subway stop throughout the city to no avail; only the boy’s remains were found.)

When Sandy hits, it threatens to overwhelm the movie. But Fleischner wisely lets the storm pass without getting swept up in the tumult. Rather, the hurricane and its aftermath are consumed by the larger task at hand: finding Ricky. And when resolution finally arrives, it feels both surreal and real — the split strands entwined once again.