The documentary Tea or Electricity captures the pivotal moment when Ifri, an isolated village in the Moroccan High Atlas, went electric. And if Belgian filmmaker Jérôme le Maire had not documented the event, it would not — could not — have been recorded. Except, of course, in the minds of the men, women, and children who were there. Surely, they will remember.

When electrical company representatives make their initial trip out to Ifri, they pass through a rural souk, or market. They chuckle at the scene and remark, “It’s a different world here.” And they aren’t even there yet. The final leg of their journey has to be made on foot, as there is no road to Ifri. When they arrive, they discover an even more alien place — one where everyone gathers eagerly around visitors. An assertive fellow named Hamed tells them that most people see their living conditions and decide it’s too difficult to help them, and another man pleads that they don’t really need electricity, what they need is a road, “an artery carrying blood to the heart.”

Standing amidst a panorama of imperious mountains, the electrical company employees assure them that the deal is done: Ifri will have electricity. They don’t mention the road.

Right away, it becomes apparent that this is going to be an uncomfortable film to watch. Not that it isn’t beautiful. After all, those expansive vistas are stunning. But it’s hard not to simply pity the residents of Ifri, so far are their lives from the comforts of modernity. Over the seasons le Maire spends recording their path to illumination (no small feat given the location), we become immersed in their way of life. A young girl wearing dusty penny loafers tromps through the snow to collect melt water; women spend their days gathering grains, their hauls piled so full on their backs that they appear from a distance to be tufted hairy beasts, teetering forward along the mountainside; when a child dies of a mysterious illness, the men carry the body away from the village and perform a simple burial. And in the spring, children get choppy haircuts with scissors.

The residents do bear some signs of the outside world. Where did those penny loafers come from? And what about that Pistons cap? How did these sartorial scraps make their way to Ifri? I’m not sure. Nor am I certain how or when this small enclave landed itself in the middle of the mountains. Tea or Electricity is watchful, but not probing.

It’s also unclear who secured this electricity contract, although some of the village men seem to think it’s just the greedy utilities company reaching far and wide for new customers. But why won’t the government etch out a road for them? Getting answers to these questions would require talking to people outside of Ifri, and that is beyond the scope of this film. Le Maire focuses intently on this place and its people. And if they are trapped without an artery, so are we.

The pace of life in Ifri guides le Maire’s approach. Scenes and conversations arise slowly and naturally, with small revelations parceled out seemingly unintentionally. Christian Martin’s lilting original score is used sparingly. In fact, Tea or Electricity seems to drag during the first half — but then again, maybe that’s just my 21st-century-paced mind. I would not have the patience, like these children, to study water-stained reading books by candlelight.

For much of the film, le Maire positions himself fairly objectively, which is easy to do when the people of Ifri aren’t convinced the electrical company will keep its word. But as the totems of infrastructure make their way up the mountain (along with a road, blasted out by the villagers who are doing the work themselves), the tone shifts. Off camera, le Maire asks the village men their opinions of the coming change. (I can only assume that the women don’t say much because of custom.) Some of the men are wary, others ambivalent. One naysayer says he’ll buy a TV, but only a small one, to watch first the evening news and then, “A beautiful film about the mountains, to see how people live, their farming, their breeding. And also to see how people die in road accidents and see how people work. We’ll learn lots of things!”

Few are unquestioningly eager — except perhaps the kids, who watch the electrical company’s progress with wonder. But many are curious. Lounging barefoot on the floor of a modest home, the light from an open-air window painting the scene in old-world chiaroscuro, three men speculate about what’s to come. One tells tales of a souk where “there are no sales people inside… A machine watches you all the time… Every item is identified by a ticket.” If I felt pity at first, now I am concerned. In moving forward, what will they leave behind? You get the sense that le Maire is worried, too.

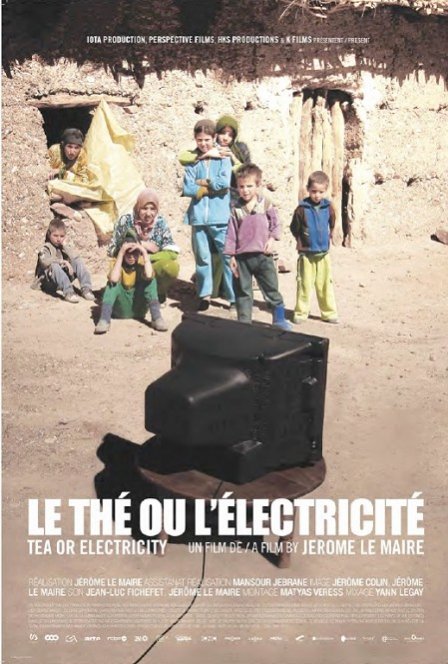

And then, without fanfare, the electricity is turned on. Light switches are tested and bare light bulbs illuminate. And le Maire’s perspective lands hard with an unsympathetic portrait of children gathered around a bulbous television. They watch commercials with rapt attention. And after almost 90 minutes of slow, sustained narrative, the quick-cut flashes feel disorienting even to me.

Later, Lahcen, a poor man with ten children who we’ve come to know quite well, sits around the fire with his family. Lahcen sold his cow to get wired, and a single light bulb shines overhead. His wife tells him that these round light bulbs aren’t good, that another villager has the long ones. Lahcen says he has also heard they are more efficient. But for now, they’ll use the one they have. Even in Ifri, they must keep up with the Joneses.

I wonder if that man has found a beautiful film about the mountains.