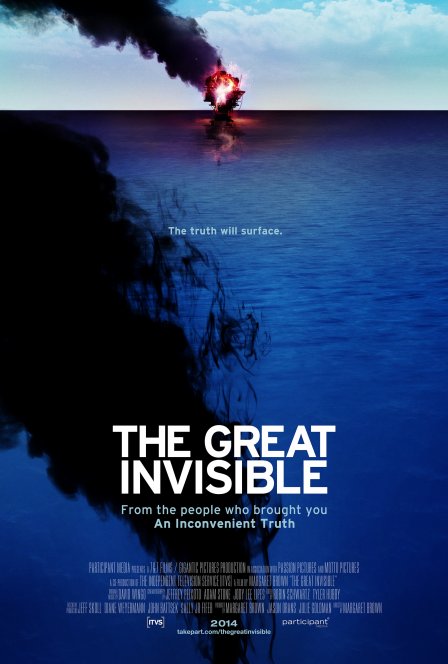

When you think of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, you may picture sludge-sopped birds, shuttered beaches dotted with tarballs, or idle fishing boats. But whatever you picture, that image is undoubtedly too simple, too narrow. Margaret Brown rectifies that in her new documentary, The Great Invisible.

The face of a disaster like this is often environmental devastation. And that indeed was one repercussion of 176 million gallons of oil pouring into the Gulf of Mexico for 87 days, the largest spill in history. But what Brown deftly reveals is that the spill affected a broader, more abstract ecosystem, one that comprises shrimpers and riggers, church volunteers and tugboat captains, the President of the United States and presidents of industry. Beyond weaving an astonishingly complex narrative (a feat of its own), Brown keeps a low profile, maintaining something that could be described as balanced subjectivity. She has sympathies, to be sure, but she is also aware that truth has many facets. This positioning elevates what might otherwise be an activist polemic, easily written off by dissenters, to something more perceptive and unsettling.

It’s hard to describe the movie’s narrative. It wends this way and that, continuously shifting from one perspective to the next. But if forced to, the story is this: on April 20, 2010, the Deepwater Horizon, an offshore rig in the Gulf of Mexico drilling the world’s deepest well, exploded. Eleven men aboard the rig died. They and their families were the most immediate and easily identifiable victims. But the ramifications rippled outward, like sonic traces of the explosion reverberating long after the Deepwater Horizon sank into the sea.

Brown portrays the disaster’s reach by amassing a wide range of subjects. There’s Doug Brown, the Deepwater Horizon’s chief mechanic; Stephen Stone, a rig worker; and Keith Jones, whose son Gordon, an engineer, was killed by the blowout. These three anchor the narrative, providing intimate accounts of the rig’s operations and the trauma caused by the explosion. Or, there’s Roosevelt Harris, a Good Samaritan who serves the community in Bayou La Batre, delivering food and helping coordinate aid efforts for the shrimpers, oyster farmers, and others whose livelihoods depend on the fruits of the sea. Some of that aid comes from a $20 billion BP-sponsored fund, administered by Kenneth Feinberg. Brown talks to him, too. There’s also Latham Smith, a tugboat captain; a cabal of oil industry fat cats (BP wouldn’t participate; it’s unclear whether Brown tried to speak with Transocean, the company that operated the Deepwater Horizon); immigrant workers who spend their days cracking crabs and pulling the meat from their limbs; and others. Does that sound like a lot of people and perspectives to cram into a 92-minute documentary? It is. But Brown handles the multitudes with aplomb. Each scene seems to flow effortlessly from the last, the crest of a wave rolling forward inevitably.

Including so many voices highlights not only the competing interests at work, but also the difficulties that arise when solutions are proposed. Public raging against offshore drilling? Enact a moratorium — except that hurts people like Latham Smith, whose tugboat business relies on the rigs. Want to avoid a drawn-out legal battle by divvying up a victims’ fund? Well-intentioned in theory, troublesome in practice; many of those affected do business with a handshake rather than a contract. Without paperwork, they can’t be compensated.

That we never feel lost amidst this tangle of stories is a testament to Brown’s approach. She may not be present onscreen — we first hear her voice when she asks an off-camera question more than an hour in — but she is present nonetheless. In particular, her hand is felt in the movie’s careful structure. In one instance, we sit at a table piled with crawfish. Latham Smith holds court, talking about how Americans wouldn’t last long without oil. Smith supports the oil industry because it supports him — and America is the driving force behind it all. The next scene opens with cars passing on a freeway. Keith Jones is driving, talking about that same, gas-guzzling culture. Though he’s describing the same phenomenon as Latham Smith, Jones sounds weary and frustrated. Brown threads these types of juxtapositions throughout the movie, maximizing the impact of each scene.

In another scene, a group of schoolchildren tour Mister Charlie, the first movable offshore oil rig, now a retired, rusty beast. During the tour, the guide explains the origins of oil. It is not, he contends, a byproduct of long-dead animals. That’s just a theory, he says. He believes, rather, that “God created the earth to sustain life,” and God gave “us” — humanity — everything we need to survive, oil included. What’s preposterous about this is the idea that nature exists to serve humans, and that we exist outside of nature. We do not. And The Great Invisible makes this abundantly clear.